I don’t really have an order to the games I enjoyed most in 2012, so I thought I’d just write something about all of them (titles of games are in bold).

When I sat down to look at my list, there was a clear trend, and it was to do with the stories I got out of those games.

Many of them had something you might call a “narrative” within them, for sure. They in quality varied from poor to completely fine, and those are not the stories I’m talking about. No, what most of my favourite games of 2012 have in common is that they led to wonderful player-generated stories, and they did so intentionally, through their systems and mechanics.

FTL was a perennial this year: with its low system requirements, it came everywhere with me on a laptop, and a short burst could fit into a lunch hour or train journey. It inevitably told tales of plucky ships fleeing the Rebellion, their crews always heroic, always doomed.

Most of my adventures in FTL end in the crew being overwhelmed by boarders; some ended when, in a vain attempt to fight back, the crew opened all the airlocks and asphyxiated alongside the boarders; and, in the cruellest twist of fate, once ended having fought off boarders, but the door control was broken, and thus all the open doors would not close… and they all died trying to shut the airlocks.

And then I swore at the screen and started again.

The word “Roguelike” gets used to describe FTL; I presume for its randomness. It doesn’t tickle my Rogue Gland in the way Torchlight or Demon’s Souls do, so I tend not to use that phrase – but it does hit the “short games, played again and again” button. I still plough on, trying to “complete” a run, but I must have made many, many attempts.

And throughout, I’m overlaying stories onto the little pixelated people on my spaceship. That’s probably because FTL followed the first rule of Generate Player Empathy: you give the characters names. Every time a new crewmember, with a new name, beamed aboard, I cheered a little for their new skillset; I yelled their name whilst they desperately tried to fix the shields; I cursed them when they failed to be any good at fixing things. But they were little people (and aliens) with little lives, and the pictures it painted in my head – helped by a youth of space sims, and a fondness for Firefly – were rich. Tom Jubert’s writing is also solid, but most of the stories in FTL I loved were the ones I made myself.

Another game that followed the “if you name it, they will cry” maxim was XCOM: Enemy Unknown. I was really, really wary of XCOM before it was released; the original UFO is massively influential for me, and one of my favourite games ever. Fortunately, Firaxis delivered a superbly apt update: a turn-based tactics and strategy game I could play from my sofa.

Most importantly, they replicated one of the original’s key features: they gave everybody a name. Not only that: they gave them arc. Every character in XCOM starts with a name and nationality – and then they develop skills, specialities; at Sergeant, they’re gifted a nickname, as well, automatically picked for their class. The longer they live, the more useful and differentiated they become – and the more those names mean.

I was somewhat attached to my Scottish sniper; when he was christened “Garotte” after he earned his stripes (I like to think, by his squadmates), it only made me like him more. He sat at the back of the formation, terse and silent, picking Thin Men and Sectoids off from afar. He made Colonel, and I become horrendously attached to him.

And I can still remember the rest of them; Roadblock, the first Major in the group, who went down on a botched operation; Caper, the South American assault trooper with an aggressive mohawk and a barking shotgun. The stories start in their names and nationalities (such a shame we only got American voice acting) – and then flow out of the game system.

Turn-based games do two interesting things for story. Firstly, they give you a chance to take stock of what’s happening, so you have more time to brood. And then: you have to interpret what’s happening a bit, and pretend it’s all really taking place simultaneously. The turn-based structure is an abstraction.

And so a little of the gameplay of XCOM happens in my head – how I join up the little boardgame on screen into the Ridley Scott movie that’s really going on. Everyone’s lasers running out of ammo before a lucky sniper bullet takes out the Muton; the rookie that gets lucky on their first mission, before getting themselves horribly trapped – and the veteran who wades into the fray to save them; the two soldiers who go everywhere hand in hand, the buddy movie stereotype, until one of them gets hit by a Chrysalid.

I suppose there’s something to be said that my point of references are genre pieces – action movies, SF. But, well, that’s what the game apes, and genre is a great way of encouraging the player to invent within a fixed framework.

Every little skirmish in XCOM is a thrilling event, even if it plays out over 20-30 minutes, not the three it likely takes at real time.

One touch that helps this narrative generation: the “ant farm” view of the base, and, specifically, that when you zoom in on the barracks, the faces you see aren’t just generic models, running on the treadmills, kicking back in the kitchen; they’re your guys. My little guys: drinking tea, jogging, and then I’m going to send them back against the aliens.

I counted them all out, I’ll tell you that much. We didn’t have to count them back; one man down, and you could feel that the Skyranger was lighter.

Speaking of boardgames, and the invention that happens between turns: the biggest story in a game I saw this year was our game of Risk Legacy.

Kieron has already written about the game at Eurogamer, but it’s worth telling again. We began the game in February, with snow on the ground; we finished the fifteenth game in December, in the frost.

Eleven months! That scale alone makes it feel like nothing else. It’s the same reason I love test cricket: you can make an epic just by pushing at the boundaries of endurance.

Eleven months is also a long while to write your own backstories. And we did: South America was laid waste early on by Imperial Balkania, who renamed it with particularly fascistic tendencies. Mark insisted on playing the same race throughout, and the one game where we took it away from him (through a particular mechanic) was so grumpy, so painful… that the retaliation he brought in the next game (simply for taking his favourites) was almost a relief. Everyone’s tendencies and preferences were enhanced, brought out, joked about; we had time to fall into character.

And again, the game has arc. As you meet the criteria for opening envelopes and boxes, the plot develops beats: a rule change means the pace of games (which had been getting out of hand) is slowed again; another adds new layers of strategy; another turns the underdogs into heroes, briefly. And the tubs… god, when we opened the first one (in easily the most memorable game of the campaign) we yelped; it completely changed everything we knew – about the board, about the rules, about the story we were telling. It reminded us that anything was possible in the game. And then we threw ourselves into telling the new story.

There’s a final, hidden packet, in the box – much-written about – that says DO NOT OPEN EVER on it. Reader, we did. I won’t spoil what was in it, but it lent the final game a particularly apt, apocalytpic feeling.

We played fifteen games, and I think we all need a break from it, but we’re going to dine out on the stories for a while.

A late entry, because it’s what I played after Christmas. Far Cry 3 is a bit of a mish-mash: it has far too many things going on at once, a hyperactive HUD, the worst loadscreen known to man, and a story that wants to ram itself down your throat. It’s not dreadful, just not strong, and a bit weird in such an open game, especially compared to how Skyrim handled the same issue.

Once you get out of the starting areas, and explore, and the systems open up and the stories start dribbling out. Deep inside Far Cry 3 is a delightful hunting game, a game about hiking (just as Skyrim was about hiking before it), a thrilling stealth game, a violent Etsy parable, and a pretty great coasteering game.

These lead to exciting stories – hiding in the bushes chasing a goat (which I need to craft with; the crafting in FC3 is nonsensical, but provides forward momentum); sneaking through an enemy base with a bow-and-arrow; driving into uncharted territory, hiking across mountains, to climb a radio tower to unlock more map. It’s in those moments that the best systems – navigation, shooting, hiding – and the beautiful environment (always varied, always colourful, worth exploring to the full) – come to the fore, and the game is at its strongest. I’m still playing it, but I’m mainly playing my Far Cry 3: the great big sunny playland to make adventure stories with. I’m worried that’ll collapse when I return to the main thrust of things.

(I wasn’t a huge fan of Skyrim’s main plot, but FC3 reminds how good it is at balancing its “main plot” with the player-generated ones; you are the Dragonborn, but you’re also leading a civil war, or a rebellion; you’re picking flowers; you’re solving crimes in towns; you’re blacksmithing. Skyrim ensures that all of these stories are compatible. Unlike Far Cry 3, which seems to be a game about your friends being captured by pirates, and your response being to go hang-gliding and flowerpicking).

I mentioned coasteering – Far Cry 3 has perhaps the best swimming I’ve seen in an FPS. It has variable speeds, sure – a gentle paddle and a crawl attached to the sprint button. But it also has excellent jumping into water – because you don’t just land on the surface; you sink, according to the velocity you hit the water with. Leaping off a cliff, Butch-and-Sundance style, isn’t met with a gentle plop, but a huge splash, a moment of unconsciousness, and the realisation you’re 12 feet down in a pool and need to swim for the surface before you pass out. It’s exhilarating every time – and also makes you much warier of shallow pools.

And no, it’s not quite the equal of Far Cry 2 for me; for every move it makes towards accessibility, it loses some of the atmosphere, the tension. For all the fun it adds, it loses some of the immersion of FC2 – even if, at times, that was immersion in things that were not fun, like the outposts.

And then there’s the big-hitter in terms of Choicy Gameplay: Dishonored. I was quite excited for Dishonored, and I think, in the end, it came off admirably. I’ve got a longer piece to write about it (juxtaposing it with a Punchdrunk show I saw), so won’t say a vast amount here.

Its great success was to make its choicyness coherent: though it had a well-written story to tell, which it told as much through beautiful environment-work as through any writing or acting (and a good thing too, given how wooden its showy cast managed to come off), it was very much a tale about my Corvo. Everyone plays a different Corvo, and even though Corvo has far less control over the direction of his tale than Shepard did over the story of Mass Effect, every single mechanic in the game helps round out what kind of man Corvo is.

Is he an assassin? Maybe, though he might not kill anyone at all throughout the game. Is he a mage? Depends how far down the path of the Outsider you want to go. Doesn’t he spend most of his spare time doing chores for Granny Rags? Not if you’re my Corvo – he didn’t speak to her once in the game, and not because he was rushing through things.

As such, it’s game (like FTL) that gets richer as you return to it, not just because you can try new paths, but also because you fill in blanks from before; every level contains multitudes, and in a very nonlinear way. My Corvo wasn’t a completist – he didn’t visit every corner of every street because he was driven, trying to further the Resistance’s goals and put a Kaldwin back on the throne. As such, returning to it, I keep playing new Corvos, discover new things, and each Corvo feels as viable and valid as the others.

Also, Blink was probably my favourite game mechanic of the year – from the way it changes the topology of levels, to its sound effect, to the way time slows as you come out of it to give the player a chance to re-orient. Very nice.

Then, there were a few other titles worth a mention because they don’t fall into this category, but they were still great:

That Borderlands 2 was very good was not a surprise; that it was as good as it turned out really was. It wasn’t just a competent sequel; it was superlative. The first game had delivered a lovely set of mechanics – randomised loot in an FPS, meaningful skill trees, fun co-op – in an unusual world that looked like nothing else. The second game took that ball and ran with it – the writing that mainly dotted quest-text in the first game now filled the universe.

One friend pointed out that whilst they might not enjoy the style of the humour and writing, its sheer consistency made it the best writing of the year. There’s a tonne of characters and dialogue here, and the jokes aren’t just limited to pop-culture references (though they’re entertaining enough); there are whole sidequests worth diving into for the dialogue alone. Every character filled out nicely, and the decision to make the previous game’s vault hunters into NPCs was a great way of expanding them from the cutouts of the previous game.

And then Gearbox re-jigged the skilltrees, giving us all manner of new stats to play with, and techniques to try. And on top of all that: they fixed the framerate issues, added even more ridiculous weaponry, and beefed up the physics and character animation – combat felt weighty and janky, like it should in the roughshod, cartoon world of Pandora.

Basically, it makes me smile every time I play it, and then it satisfies my game-mechanics gland, and it’s such a polished package – without (nota bene, Far Cry 3) being overloaded with systems and mechanics. Very, very good stuff, and the fact that all the DLC to date has been great is just a bonus for its life.

It’s nice to be able to recommend a non-violent game; now is not the time for another conversation about violence and games, but I do note that there’s a lot of Direct Conflict in the list. That’s partly my taste for technical, involved games; partly a heritage that stretches from Quake onwards; but it’s not deliberate. I played a lot of other non-violent games this year, but these are the ones that stuck in the memory. Sorry, people.

And yet: how lovely to say that Fez delighted and cheered me as I played through it in the summer.

It had been trailed so long I was a bit tired of it; the rotating of the Trixel engine looked like its One Gag. So how delightful to discover that it had far more to give than that: a delicate, minimal narrative; lots of Actual Puzzles buried in frequency analysis and lateral thinking; beautiful artistic jokes; a wonderful soundtrack, to which I only have to listen in order to be transported back; a huge, well-realised world.

For a few months, the TV had bits of notepaper with Fez-language all over them, and a pen, for when I needed to take notes. It’s a long while since I’ve played a game that needed pen and paper.

And then, on all that, there’s Gomez’ charming animation, the fluidity of navigation that you can get to when you get good at the game, the fiero when you suss a puzzle. Really, really good, ignoring all the hoo-haa that surrounded it.

Of course, a couple of games tried to tell a decent story, and had the balls to actually do it right for once.

I’ve not played much of The Walking Dead, but it’s clearly quite a thing – and something I definitely want to finish.

In many ways, it’s a barely-game: it’s not exactly full of Deep Systems. But it’s still very much on the game-spectrum, because at its heart are a long series of meaningful choices.

Meaningful choices, by the way, is one of Firxais’ key tenets of good game design. And they made XCOM and Civilisation, so they’re probably onto something.

What Walking Dead does so well is not, really, the choices per se; it’s how it imbues them with meaning. It imbues them with meaning simply through… good writing. That’s it. Not “good for games”, just good. Chris Remo made this point nicely on Idle Thumbs: he pointed out that whilst it’s very commendable to be trying to advance storytelling in games through mechanics and systems that inherently drive narrative, and narrative that’s assonant with those game mechanics… you could also start by putting better writing in games.

Much as I’m a systems-advocate, he’s right; there are two forks to this attack, and we shouldn’t forget that second one.

To that end, The Walking Dead (much like its source material, and like all good post-apocalyptic fiction) pushes the zombies right to the background, and focuses on its human tale. And then, through wonderful writing (and perfectly stylised art) it makes you care about its gang of survivors; it’s human, well-realised, realistic. Which means making choices about them hard. And better still: it logs those choices in the long term. This isn’t about the turgid binary good/evil decisions that dog games; this is about somebody remembering something you did days ago and it coming back to haunt you.

Also, it’s on almost every platform and playable by almost anyone, which is probably a good anecdote to the highly technical gameplay I usually recommend. Anyhow: if you’re interested in the state of commercial Interactive Fiction, this is a great place to start.

Or you could play 30 Flights Of Loving, which pips Walking Dead for my favourite game narrative in 2012 – and I only played it a few days ago.

It is fifteen minutes long, or therabouts.

And yet: look at all the things it crams in; look at the storytelling techniques it uses. When you’re using as swift an engine as the Quake 2 one, smash-cuts become a thing you can use (because you don’t have the memory pipeline issues of a modern, hi-res game). It’s the first time in ages I’ve seen a game embrace non-linear editing like film did – and yet it’s not a lift from film; in a first-person, subjective viewpoint, it’s far weirder than that.

A smash cut takes me to new geometry – have I teleported? Is this a bug? Has time gone forwards or backwards? Only by paying attention will you work it out. And, just as you do, the narrative lurches again.

There’s so much in it, such condensation, like the best short stories or movies: it takes fifteen minutes to play, but it will stay with you days (as Christian points out in his excellent Eurogamer write-up).

Maybe it’s just an experiment – but it’s such a challenging, dynamic, exciting one, it makes me wonder what a few hours of it would feel like. Anyhow: it’s just wonderful, and is probably my best counterpoint to the exciting things you can tell with games that aren’t just player-generated narratives. Good stuff.

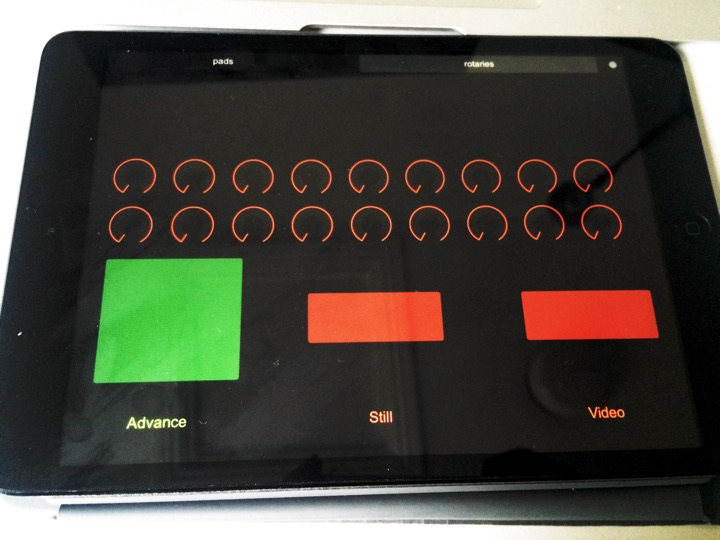

There were many other great games in 2012 – some I played, some I didn’t, and I don’t quite have the energy to talk about SPACETEAM other than to say yes, it also leads to the best kinds of emergent stories, mainly from its spectators – but these are the ones I wanted to share. Gosh, that was long, though.