-

Using page.js as a really lightweight router for Svelte – worked very well, it turned out.

-

Whilst I'm an old-fashioned developer, sometimes I need to make something like an SPA, and I really like how lightweight and simple this routing library is – not to mention its excellent set of plain js examples. Really good.

-

Because we all forget things, and this is a nice, tidy list of simple HTML DOM wrangling (which I frequently have to do, and like to do as simply as possible).

-

Everest Pipkin's vast list of free tools and tool-likes for making games, interactive things, art, and so on. Comprehensive, worth diving into several times.

The Thing That Gets You To The Thing

23 March 2020

I finished my rewatch of (all of) Halt and Catch Fire. I blame Robin for the push. And now, rather than just emailing my three friends who definitely care, I’m writing about it online.

Halt is one of my favourite TV shows. It took me a while to realise this, the first time around: I think I actually knew that for sure around season 3 (of 4). The final season is definitely my favourite final year of a show ever.

And here’s the thing, really, I just wanted to watch season 4 again. But season 4 doesn’t taste so good without the build-up to it. Really, I was signing up to go on a journey: I wanted to ride the rollercoaster again, and I wanted the end of season four to hurt in all the ways it does, to heal in all the ways it does. I wanted to rebuild my relationships with these characters precisely to feel a specific moment of grief in all the right ways.

(That moment landed, just as well as the first time, and everything else – the joy, the kindness, the friendship, the delight of watching reconciliation – landed too).

It’s a funny show. It starts out… quite badly, wanting to tell one particular story, and the moment it starts swerving away from that, it becomes more interesting. That point isn’t the beginning of season 2, incidentally: it’s easy to hate on the messy first season, but rewatching it, it confirmed that it course-corrects fast and hard. Once Donna is brought up in the mix around S1E4 it starts showing hints of what it’ll be, and the last few episodes of season 1 – pretty much once Donna says “I’m coming with you,” and the gang drives to COMDEX, are it taking flight. The rewatch definitely confirmed you cannot pull the “Parks And Rec Manouevre” (“just start with S2”) with this show.

But: it definitely improves, and it is one of the most impressive instances of a show seemingly deciding that it wasn’t working, changing everything up, and that actually working. What worked was, of course, the ensemble. What didn’t work was The Joe MacMillan Show. But Joe is a great character – maddening, obnoxious, and then at key times, not. So his role shifts up, and new characters get the spotlight in S2 – and that shift of focus keeps happening. Throughout the run, the structure of the show and the roles played by the same characters are constantly rejigged: who has power? Who wants it? Who is satisfied? Who is unfulfilled?

It’s easy to comment on how successfully the show reinvented itself. I think, though, that the way that also happens diegetically is perhaps my favourite thing about the show.

More plainly: Halt and Catch Fire is one of my favourite dramatic depictions of change.

Drama is largely about conflict and tension, and how that can be resolved: successfully for all, or with winners and losers. Characters change (or they don’t) in order to get what they want. But Halt does something more interesting: characters also change because life happens, and it changes them. It plays out over about 12 years, and one of my favourite things in the show is how the characters age, how they escape their old loops, how they become more themselves, and where they end up.

I get a little bit teary watching the Joe of the beginning of season 4: broken by so many things that have happened, smaller and subdued. But, quickly, it becomes clear that in some ways, he is happier and healthier. Watching him finally find ways to be happy but not at the expense of others; watching him work out how to be kind (and also watching others finally trust him, having understandably not trusted him for so long); watching his relationship with Haley, is a delight.

There’s a mirror to that in Cameron, too, who – once she escapes the lazy writing of the early episodes – takes off as a character. Cameron drives me absolutely spare for much of the show, and this is why I like the character; she is brilliant and frustrating, and the point of her character is that she cannot be one without the other. She drives me mad, and I love her nonetheless. I like seeing her win, feel for her many vulnerabilities, and hate seeing her hurt. She’s wrong (practically, but not ideologically), I think, about the inevitably terrible IPO, but I never forget Mackenzie Davies’ guttural scream when she’s voted down, and thus out of her own company. I never stopped hating that she had to feel that way.

The common thread for all the four leads is how terrible and unhealthy their relationships can be, and how much work it takes for them to even understand this, before they fix it. They think they can fix it through divorce, or estrangement, or destruction; what it takes is grief, and forgiveness, and acceptance, and time.

I rewatched because I wanted to watch the knot come undone, and then watch the characters tie it back together again. There is an unnameable pleasure in watching Joe work out how to be friends with Gordon, how deep his love for his business partner ultimately runs, after years of working together unhealthily. I love watching Cameron work out that she actually really likes Gordon as a pal when they don’t work together. I love that Cameron learns how to have the solitude and independence she knows she requires but also how not to push friends away. And I love that these are not things they earned through the twists of a few weeks that return them to where they began, but changed; I love that these are all-consuming changes, that take years to land. At the end of S4E10, it feels like so many of them are finally beginning.

And of course: it’s notable that their personal relationships reflect their work. Sat with me as I watched the end, my partner – who hasn’t really seen the show – asked if Comet was going to be another failure. And I said: “sort of, through no fault of its own. And Comet isn’t even the most successful company anybody runs during the series, or the best idea, really – but it is the healthiest, and that feels worth something“. Joe and Gordon make a place that really does work, for them, and everyone inside it, and they both learn that that perhaps beats being first, or best, or richest.

(Incidentally: I really like how the show manages to make its characters look ahead of their time and still fail. They exist in our world, but the reason you’ve never heard of them is they got beaten to the punch. All that drama in S1 trying to build a computer for the masses, a computer with personality, and getting it almost right, is neatly undercut by the moment Joe sees a pre-release Macintosh at COMDEX, and Lee Pace just sells a man seeing the thing he’s been talking about for so long made flesh, made better than he could ever have conceived, and made by somebody else.)

I’d never have put money on Halt being the show that made me feel these ways back in the dark days of a first watch of S1. Some shows are comfort-viewing because they’re about people who ultimately, feel like friends; they are nice to be with, they reassure you, any threat is short-lived. Halt is a deeper comfort, that is not always comfortable: the comfort of family. Family (the ones you have, the ones you choose, it doesn’t matter) are not always perfect, conflict is not always easily resolved, and people dear to you can still be entirely infuriating: but these feelings and conflicts are real because of how deeply they are felt. And that means that a comfort-watch about familial comfort is not always feel-good: by the end, I am watching not just to spend time with these characters I’ve come to love so deeply, but to support them; to hurt with them.

I wanted to feel all those things again, and I wanted to earn those feelings. The time-jump in NIM; the end of Who Needs A Guy; god, all of Goodwill; those moments land more because of everything invested. But most of all, like watching a plant grow, I wanted to watch people change, to be reminded that they can, and to see them learn to love themselves, because by the end, Halt and Catch Fire makes it clear exactly how hard that can be, and exactly how worth the effort to do so it is.

-

Great piece of games journalism from Duncan Fyfe: the history and legacy of Mastermind. Wide-ranging, great bits of research. Love it.

"The earliest reference to Bulls and Cows is in the work of Dr. Frank King. In 1968, King was studying for a PhD in electrical engineering at Cambridge University and looking for something to implement on the university's Titan computer, which had recently been equipped with Multics, a time-sharing operating system allowing multiple users to access one computer concurrently and remotely.

Thinking a game would be enjoyable, and something more sophisticated than Tic-Tac-Toe even better, King wrote a version of a childhood puzzle. "Good grief, you've implemented Bulls and Cows," he remembers other students saying, though he called it MOO."

-

Because I'm always losing this post when I'm looking for documentation for these scripts…

-

This is wonderful: Rrose talks about their process, which ends up on techno and psychoacoustics… but is mainly about player pianos as well. Very good indeed, and a great interview.

-

I have been trying to understand pointers for 25 years and this might be the clearest explanation I've read.

planetary, a sequencer.

01 March 2020

I wrote a music sequencer of sorts yesterday. It’s called planetary.

It looks like this:

and more importantly, it sounds and works like this:

In short: it’s a sequencer that is deliberately designed to work a bit like Michel Gondry’s video for Star Guitar:

I love that video.

I’m primarily writing this to have somewhere to point at to explain what’s going on, what it’s running on, and what I did or didn’t make.

It runs on a device called norns.

Norns

norns is a “sound computer” made by musical instrument manufacturer monome. It’s designed as a self-contained device for making instruments. It can process incoming audio, emit sounds, and talk to other interfaces over MIDI or other USB protocols. A retail norns has a rechargeable battery in it, making it completely portable.

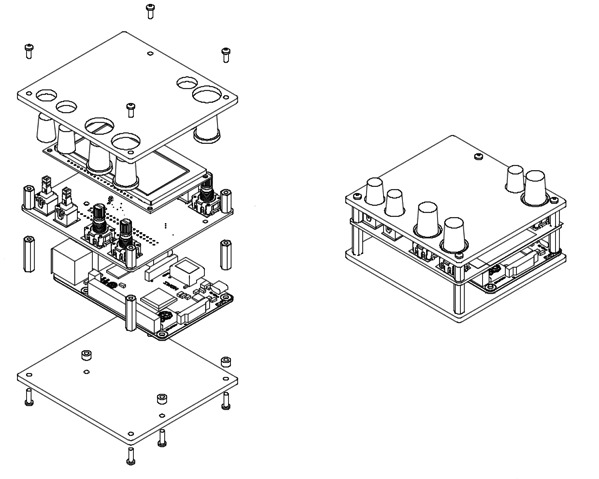

There’s also a DIY ‘shield’ available, which is what you see in the above video. This is a small board that connects directly to a standard Raspberry Pi 3, and runs exactly the same system as the ‘full-fat’ norns. (A retail norns has a Raspberry Pi Compute Module in it). You download a disk image with the full OS on, and off you go. (The DIY version has no battery, and mini-jack I?O, but that’s the only real difference. Still, the cased thing is a thing of beauty.).

norns is not just hardware: it’s a full platform encompassing software as well.

norns instruments are made out of one or two software components: a script, written in Lua, and an engine, written in SuperCollider. Many scripts can all use the same engine. In general, a handful of people write engines for the platform; most users are writing scripts to interface with existing engines. Scripts are certainly designed to be accessible to all users; SuperCollider is a little more of a specialised tool.

Think of a script as a combination of UI processing (from both knobs/encoders on the device, and incoming MIDI-and-similar messages), and also instructions to give to an engine under the hood. An engine, by contrast, resembles a synthesizer, sampler, or audio effect that has no user interface – just API hooks for the script to talk to.

The scripting API is simple and expressive. It lets you do things you’d need to do musically, providing support both for screen graphics but also arithmetic, scale quantisation, and supporting a number of free-running metro objects that can equally be metronomes or animation timers. It’s a lovely set of constraints to work against.

There’s also a lower-level thing built into norns called softcut which is a “multi-voice sample playback and recording system” The best way to imagine softcut is as a pair of pieces of magnetic tape, a bit over five minutes long, and then six ‘heads’ that can record, playback, and move all over the tape freely, as well as choosing sections to loop, and all playing at different rates. As a programmer, you interface with softcut via its Lua API. softcut can make samplers, or delays, or sample players, or combinations of the above, and it can be used alongside an engine. (Scripts can only use one engine; softcut is not an engine, and so is available everywhere.)

norns even serves as its own development environment: you can connect to it over wifi and interface with maiden, which is a small IDE and package manager built into it. The API docs are even stored on the device, should you need to edit without an internet connection.

In general, that’s as low level as you go: writing Lua, perhaps writing a bit of Supercollider, and gluing the lot together.

Writing for norns is a highly iterative and exploratory process: you write some code, listen to what’s going on, and tweak.

That is norns. I did none of this; this is all the work of monome and their collaborators who pieced it together, and this is what you get out of the box.

All I did was build my own DIY version from the official shield, and create some laser-cut panels for it:

…which I promptly gave away online.

Given all that: what is planetary?

Planetary

To encourage people to start scripting, Brian – who runs monome – set up a regular gathering where everybody would write a script in response to a prompt, and perhaps some initial code.

For the first circle, the brief gave three samples, a set user interface, and a description of what should be enabled:

create an interactive drone machine with three different sound worlds

- three samples are provided

- no USB controllers, no audio input, no engines

- map

- E1 volume

- E2 brightness

- E3 density

- K2 evolve

- K3 change worlds

- visual: a different representation for each world

build a drone by locating and layering loops from the provided samples. tune playback rates and filters to discover new territory.

parameters are subject to interpretation. “brightness” could mean filter cutoff, but perhaps something else. “density” could mean the balance of volumes of voices, but perhaps something else. “evolve” could mean a subtle change, but perhaps something else.

I thought it’d be fun to take a crack at this, and see what everyone else was up to.

A thing I’ve found in my brief scripting of norns prior to now is how important the screen can be. I frequently think about sound, but find myself drawn to how it should be implemented or appear, or how the controls should interact with it.

So I started thinking about the ‘world’ as more than just an image or visualisation, but perhaps a more involved part of the user interface, and then I thought about Star Guitar, and realised that was what I wanted to make. The instrument would let you assemble drones with a degree of rhythmic sample manipulation, and the UI would look like a landscape travelling past.

The other constraint: I wanted to write in an afternoon. Nothing too precious, too complex.

I ended up writing the visuals first. They are nothing fancy: simple box, line, and circle declarations, written fairly crudely.

As they came to life, I kept iterating and tweaking until I had three worlds, and the beginnings of control over them.

Then, I wired up softcut: the three audio files were split between the two buffers, and I set three playheads to read from points corresponding to each file. Pushing “evolve” would both reseed the positions of objects in the world, and change the start point of the sample. Each world would run individually and simultaneously, and worlds 2 and 3 would start with no volume and get faded in.

The worlds also run at different tick-rates, too: the fastest is daytime, with 40 ticks-per-second; space runs at 30tps, and night runs at 20tps.

I hooked up the time of day to filter cutoff, tuned the filter resonance for taste, and then mainly set to work fixing bugs and finding good “starting points” for all the sounds.. On the way, I also added a slight perspective tweak – objects in the foreground moving faster than objects at the rear – which added some nice arrhythmic influence to the potentially highly regular sounds.

In the end, planetary is about 300 lines of code, of which half is graphics. The rest is UI and softcut-wrangling – there’s no DSP of my own in there.

I was pleased, by the end, with how playable it is. It takes a little preparation to play it well, and also some trust in randomness (or is that luck?. You can largely mitigate that randomness by listening to what’s happening and thinking about what to do next.

Playing planetary you can pick out a lead, add some texture, and then pull that texture to the foreground, increasing its density to add some jitter, before evolving another world and bringing that forward. It’s enjoyable to play with, and I find that as I play it, I both listen to the sounds and look at the worlds it generates, which feels like a success.

I think it meets the brief, too. It’s not quite a traditional drone, but I have had times where I have managed to dial in a set of patterns that I have left running for a good half hour without change, and I think that will do.

planetary only took a short afternoon, too, which is a good length of time to spend on things these days. I’ve certainly played with it a good deal after I stopped coding. It’s certainly encouraged me to play with softcut a bit more in the next project I work on, and perhaps to keep trying simple, single-purpose sound toys, rather than grand apps, on the platform.

Anyhow – I hope that clarifies both what I did, and what the platform it sits on does for you. I’m looking forward to making more things with norns, and as ever, the monome-supported community continues to be a lovely place to hang out and make music.