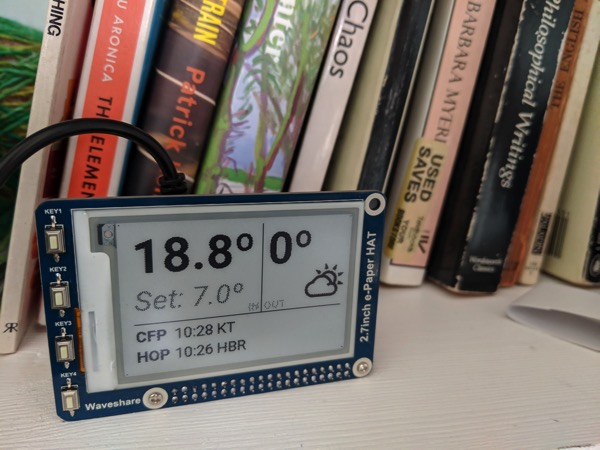

I made a small display for my living room.

This project began when we installed a Hive thermostat at home. For various reasons, the thermostat ended up on the upstairs landing, and I thought it’d be nice to have a second display for it downstairs. I know I can look at the app on my phone, but I thought something more ambient might be nice. And, whilst I was at it, one feature I’d always wanted – the next trains at my nearest stations – and perhaps the outdoor temperature and weather as well.

This all coincided with Bryan Boyer writing up his Very Slow Movie Player project, which is a delight. (It shows a movie at a frame a minute, on a large e-ink screen).

I’ve been fascinated with e-ink for a long while. I’m well into the lifespan of my second Kindle, and it’s such a wonderfully un-technological piece of technology. It’s still, to my mind, the single best piece of hardware Amazon have made by a long, long way.

I wrote about the joy of e-ink when I was at Berg, in Asleep and Awake. As Bryan proved, it’s now fairly easy to both source e-inks screens and also to interface with them. The 2.7″ screen I used came ready-attached to a Raspberry Pi HAT, with libraries all written for it.

(As an aside: I’ve been tinkering with Raspberry Pis for a while, but this was the first time I’ve used the Zero form factor; the £10 Zero W, with built-in wireless and bluetooth, is such a lovely fit for this project. It does make the thought of doing lower-level embedded work seem a little foolish for simple IOT prototypes – lots of power and connectivity, and the ability to write high-level code is a delight.)

So: I had a screen, and a Pi. I started with the output: getting a PNG of mocked-up UI to display on the screen. This didn’t take too long, although I’ve had no joy getting partial updates to work – I’m using a fairly heavyweight full screen refresh each time the screen updates. Still, that’s an improvement I can come to later.

With the sample PNG on the screen, there were two remaining strands of work: dynamically generating images, and gathering data to feed them. Again, I worked on the former first, using Pillow. I’m not a great Python developer by any stretch, but a recent work project featuring a lot of it made me a lot more comfortable with hacking on the language, and Pillow’s a lovely tool for simple image compositing. Google’s Roboto font and Erik Flowers’ WeatherIcons do most of the legwork; the rest is simple compositing, step by step.

Once the Python image processing was written, I moved onto data-scraping. I’m happiest in Ruby, but chose Javascript for this work. Why? Partly for how appropriate it was for dealing with lots of JSON, and partly to get more familiar with ES6. I ended up with three scripts: one to get the latest set and actual temperatures from the Hive API; one to get the next trains at some stations; and one to query the Dark Sky API for local weather. These would write out to JSON via lowdb. Then, the Python script could, separately, read that JSON directly, render a PNG, and trigger a refresh of the screen.

Having broken the task down, everything went almost entirely as planned. One by one, I replaced each section of the screen with live content. The only hiccups were the usual wrestling with cron jobs (when do these ever go smoothly?) and dealing with simultaneous writes to the JSON store. (It turned out lowdb wasn’t great for distributing across multiple files, and rather than rewrite everything to use SQLite, I just went with three separate JSON files. Easy fix). Nice to spend a few hours at the weekend motoring on some programming I’m entirely comfortable with: JSON, markup-scraping, server-side fettling and graphics processing.

I’m happy with the results. There’s a bit of a distracting blink when the display re-renders, but the lack of a glow makes it feel very different to a more obviously electronic device. It just sits, comfortable with itself, giving me a little bit of information. I was surprised how many people enjoyed it when I shared it on Instagram, so thought I’d write it up.

What’s next? I might add something else to that lower-right display; not sure what, yet. And, most importantly, I’m going to give it some kind of case – it’s a bit too ‘gadgety’ or ‘maker-y’ as it stands; it needs to be made more homely. Perhaps some wood. In the meantime, though, I’ve been living with it, and had no desire to repurpose it, or switch it off, which is usually the best sign.

Most notably: it continues to affirm my belief that e-ink is a most gentle and domestic technology. I can confirm that it’s now very easy to play with, if you’re so inclined; a Python library and bolting a £30 HAT onto a Pi was all this took to get live. I might do some more tinkering with this technology in due course.