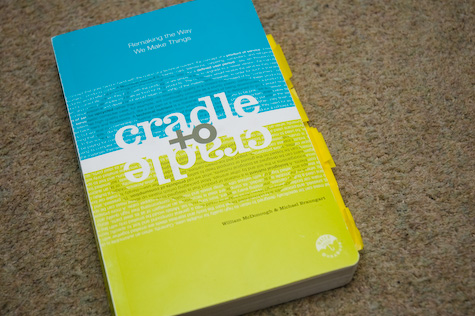

Any way you look at it, William McDonough and Michael Braungart’s Cradle to Cradle is an unusual book.

It’s a book that invites the reader to envisage a world in which the concept of waste does not exist, and where re-use is preferred to recycling; in short, a world where products have a true life-cycle, rather than a passage from cradle-to-grave.

It’s an exciting book, if only because the physical artefact embodies its message:

Cradle to Cradle is not made out of paper, you see. It’s a format called Durabook. The Durabook is made of a kind of plastic, and is entirely waterproof. More interestingly, it’s entirely reusable – the ink can be easily removed to allow reprinting or notebook use, and the “paper” itself can be melted down and reused without giving off toxins. It’s a good environmental citizen, essentially: reusable, up-cyclable, and with no harmful byproducts. (It’s also surprisingly heavy for such a slim format).

I found it an interesting read. I found a lot of their later commentary on designing services probably the most interesting and relevant – a lot of discussion on refactoring products (which, by their nature, are designed for disposal) into services (wherein the product can be upcycled or removed from the equation, as it’s the service that matters). The Linc concept mobile phone is a good illustration of the thinking the book suggests.

At times, though, I found it depressing; a lot of the innovations pointed to are McDonough and Braungart’s own, and it would have been good to see more examples from people other than them. Similarly, at times the scale of the challenges described in the book seems colossal, and perhaps impossible.

But I think, taken with a pinch of salt, it’s an interesting read, and there’s some good meat within it. With that in mind, here’s what I marked out for myself as being interesting:

p.24, on Henry Ford’s innovations:

“In 1914, when the prevailing salary for factory workers was $2.34 a day, he hiked it to $5, pointing out that cars cannot buy cars. (He also reduced the hours of the workday from nine to eight). In one fell swoop, he actually created his own market, and raised the bar for the entire world of industry.”

I really enjoyed the section on Ford. They point out that a lot of Ford’s innovations really were more environmentally-friendly than the wasteful, inefficient factories that had preceded them. This doesn’t make it good, per se, but it’s worth bearing in mind. And I love “cars cannot buy cars”.

p.46, on the sentiments of the American Pastoral writers:

“[Aldo] Leopold anticipated some of the feelings of guilt that characterise much environmentalism today:

“When I submit these thoughts to a printing press, I am helping cut down the woods. When I pour cream in my coffee, I am helping to drain a marsh for cows to graze, and to exterminate the birds of Brazil. When I go birding or hunting in my Ford, I am devastating an oil field, and re-electing an imperialist to get me rubber. Nay more: when I father more than two children I am creating an insatiable need for more printing presses, more cows, more coffee, more oil, to supply which more birds, more trees, and more flowers will either be killed or … evicted from their several environments.”

p.60, on the struggle between what Jane Jacobs described as commerce and the guardian:

“Any hybrid of these two syndromes Jacobs characterizes as so riddled with problems as to be ‘monstrous’. Money, the tool of commerce, will corrupt the guardian. Regulation, the tool of the guardian, will slow down commerce.”

p.61, on regulation being a signal of design failure:

“In a world where designs are unintelligent and destructive, regulations can reduce immediate deleterious effects. But ultmiately a regulation is a signal of design failure. In fact, it is what we call a license to harm: a permit issued by a government to an industry so that it may dispense sickness, destruction, and death at an ‘acceptable’ rate.”

p.66-67, on sacrifice and “eco-efficiency” as a way of trying to cut down on the bad things humans do:

“In very early societies, repentance, atonement, and sacrifice were typical reactions to complex systems, like nature, over which people felt they had little control. Societies around the world developed belief systems based on myth in which bad weather, famine, or disease meant one had displeased the gods, and sacrifices were a way to appease them…

But to be less bad is to accept things as they are, to believe that poorly designed, dishonorable, destructive systems are the best humans can do. This is the ultimate failure of the ‘be less bad’ approach: a failure of the imagination. From our perspective, this is a depressing vision of our species’ role in the world.

What about an entirely different model? What would it mean to be 100 percent good?”

It takes them a while to get to that point (in a ~180 page book), but that’s the real kicking-off point for the more interesting arguments – by reframing the problem in a world that doesn’t have a concept of waste, what kind of answers emerge?

p.70, on rethinking the “entire concept of a book” (which is something the artefact of Cradle to Cradle itself does, as mentioned earlier):

“We might begin by considering whether paper itself is a proper vehicle for reading matter. Is it fitting to write our history on the skin of fish with the blood of bears, to echo writer Margaret Attwood?”

p.80, on “nature’s services”:

“Some people use the term nature’s services to refer to the processes by which, without human help, water and air are purified […] We don’t like this focus on services, since nature does not do any of these things just to serve people.”

True “services” have to intend to service a particular need – you can’t just apply the s-word to any available substrate or process.

p.84:

“Western civilization in particular has been shaped by the belief that it is the right and duty of human beings to shape nature to better ends; as Francis Bacon put it, ‘Nature being known, it may be master’d, managed, and used in the services of human life.‘”

p.87, on new approaches to zoning:

“We agree that it is important to leave some natural places to thrive on their own, without undue human interference or habitation. But we also believe that industry can be so safe, effective, enriching, and intelligent that it need not be fenced off from other human activity. (This could stand the concept of zoning on its head; when manufacturing is no longer dangerous, commercial and residentail sites can exist alongside factories, to their mutual benefit and delight.)”

That would make Sim City interesting.

p.88; professor Kai Lee talks to members of the Yakima Indian Nation about the long-term plans for storing nuclear waste within their territory.

“The Yakima were surprised – even amused – at Kai’s concern of their descendants’ safety. ‘Don’t worry,’ they assured him. ‘We’ll tell them where it is.’ As Kai pointed out to us, ‘their conception of themselves and their place was not historical, as mine was, but eternal. This would always be their land. They would warn others not to mess with the wastes we’d left.

We are not leaving this land either, and we will begin to become native to it when we recognize this fact.”

This reminds of Tom Coates’ Native to a Web of Data – we will become native to the web when we recognise that the data structures we create and impose on it will stick around forever, and that we should design them as such.

p.102, on “deflowering” a new product:

“Opening a new product is a kind of metaphorical defloration: ‘This virgin product is mine, for the very first time. When I am finished with it (special, unique person that I am), everyone is. It is history.’ Industries design and plan according to this mind-set.”

p.103:

“What would have happened, we sometimes wonder, if the Industrial Revolution had taken place in societies that emphasize the community over the individual, and where people believed not in a cradle-to-grave life cycle but in reincarnation?”

p.104, describing the two discrete metabolisms of the planet:

“Products can be composed either of materials that biodegrade and become food for biological cycles, or of technical materials that stay in closed-loop technical cycles, in which they continually circulate as valuable nutrients for industry. In order for these two metabolisms to remain healthy, valuable, and successful, great care mus be taken to avoid contaminating one with the other.”

p.120: fittest vs fitting-est

“Popular wisdom holds that the fittest survive, the strongest, leanest, largest – perhaps meanest – whatever beats the competition. But in healthy, thriving natural systems it is actually the fitting-est who thrive. Fitting-est implies an energetic and material engagement with place, and an interdependent relationship to it.”

p.128, on misunderstanding Le Corbusier’s intent:

“Modern homes, buildings, and factories, even whole cities, are so closed off from natural energy flows that they are virtual steamships. It was Le Corbusier who said the house was a machine for living in, and he glorified steamships, along with airplanes, cars, and grain elevators. In point of fact, the buildings he designed had cross-ventilation and other people-friendly elements, but as his message was taken up by the modern movement, it evolved into a machinelike sameness of design.”

p.144, on people’s affinity for certain types of visual:

“According to visual preference surveys, most people see culturally distinctive communities as desirable environments in which to live. When they are shown fast-food restaurants or generic-looking buildings, they score the images very low. They prefer quaint New England streets to modern suburbs, even though they may live in developments that destroyed the Main Streets in their very own hometowns. When given the opportunity, people choose something other than that which they are typically offered in most one-size-fits-all designs: the strip, the subdivision, the mall. People want diversity because it brings them pleasure and delight. They want a world of [paraphrasing Charles De Gaulle] four hundred cheeses.”

p.154, on criteria for new product design:

“High on our own lists [of criteria] is fun: Is this product a pleasure, not only to use, but to discard? Once, in a conversation with Michael Dell, founder of Dell Computers, Bill observed that the elements we add to the basic business criteria of cost, performance, and aesthetics – ecological intelligence, justice, and fun – correspond to Thomas Jefferson’s ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’. Yes, Dell responded, but noted we had left out a most important consideration: bandwidth.”

p.172, on the aspects of marketing and selling eco-friendly products:

“A small but significant number o consumers chose to buy the lotion in a highly unattractive ‘eco’ package shelved next to the identical product in its regular package, but the number who chose the ‘eco’ package skyrocketed when it was placed next to an over-the-top ‘luxury’ package for the very same product. People like the idea of buying something that makes them feel special and smart, and they recoil from products that make them feel crass and unintelligent. These complex motivations give manufacturers power to use for good and for ill. We are wise to beware of our own motivations when choosing materials, and we also can look for materials whose ‘advertising’ matches their insides, again as indicative of a broader commitment to the issues that concern us.”

p.185, in a section on “preparing for the learning curve”:

“Biologist Stephen Jay Gould has captured this concept nicely in a way that can be useful to industry: ‘All biological structures (at all scales from genes to organs) maintain a capacity for massive redundancy – that is, for building more stuff or information than minimally needed to maintain an adaptation. The ‘extra’ material then becomes available for constructing evolutionary novelties because enough remains to perform the original, and still necessary, function’. Form follows evolution.”

And that’s all, really. I enjoyed it a lot – though I found its message difficult and overfacing at times, and the perspective perhaps a little smug, there was lots of good stuff in it and it provided food for thought. Thanks to Tom for letting me borrow it, and to Mike for the format this blogpost takes.