Some notes on the ongoing decline of Twitter for its non-human users, with lots of fractal links out to other things I’ve written in the past.

I’ve been messing around on Twitter for a really, really long while. Not just typing in the box about my lunch, but also making daft things that live on it. And it turns out I’ve been writing about that place and those things for quite a while too.

The earliest thing I wrote about Twitter here was, I think, about it as some kind of universal, human-readable, messaging bus. Norm reminded me of this online a while ago, and rereading that, this whole post began to snowball in my head.

I wrote it around the time the Jodrell Bank telescopes started tweeting. Their posts were only loosely human readable… but I’d definitely characterise them as human-interesting: they were the burbling, background-noise of life going on – except this time, it was things talking about doing things, not people talking about doing things. The flickering of the metaverse.

That post is a rare discovery for me: something I almost entirely agree with, eleven years on, and that acts as a useful touchpoint for so much of my later work. I won’t summarise it again; it’s worth a re-read, if only to see what it looked like something could be circa 2007, with only the simplest functionality to go on.

Also: it was an idea that sparked something in me, and would act a little as a lynchpin for a succession of projects.

It also coincided with my programming capabilities being… less terrible. At the time, I worked around the corner from Tower Bridge, and one lunch-hour in 2008 I put together a small piece of code to scrape the publicly published list of bridge times and publish to Twitter roughly when the bridge was opening or closing. Not out of a sense of a utility, though. If anything, I just wanted to see what it’d be like to share my timeline with non-human actors that figured in my life.

I wrote about @towerbridge when I launched it. The image illustrating the post has gone since Skitch went offline; the bot itself has moved and is non-functional right now. But the idea holds true; it still feels like a robust one – and a foundational one for me. And this paragraph is something hugely fundamental for me:

As a note on its design: it’s very important to me that the bridge should talk in the first person. Whilst I’m just processing publicly available data on its behalf, Twitter is a public medium for individuals; I felt it only right that if I was going to make an object blog, the object should express something of a personality, even if it’s wrapped up in an inanimate object describing itself as “I”.

Good actors in systems behave according to the rules of those systems. At the time, Twitter asked you What are you doing?, and so you needed to answer that. If you want a great example of this, the code behind Jim Kang’s wonderful Appropriate Tributes is a fantastic read – it does a lot of work to do its best to respond sensitively, not barge in on conversation, or pick up on inappropriate topics; that feels like base-level interactions for making a non-human actor.

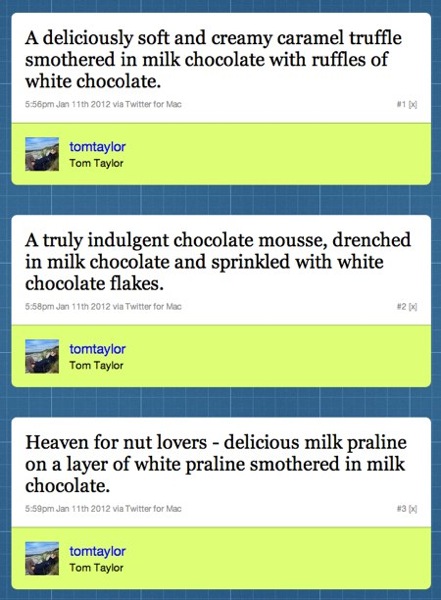

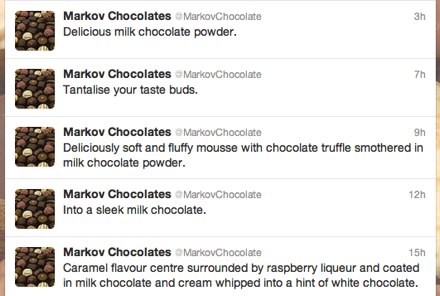

Twitter was a perfect combination of a simple API, a strong set of constraints, and permalinks. It was the easiest place to publish tiny content-y things, give them permanent URLs, and make them web-ish. So more toys followed, that I wrote up. An automated joke. An endless box of chocolates, my first foray into Markov chains and statistically-generated prose (oh, the amount of time I’ve spent explaining that Markov chains know nothing about language). Four bots that sounded like they were hunting zombies together. (A bit of a hack, that: Twit 4 Dead was really four actors reading a prepared script together, rather than genuinely responding to each other. I started work on the latter for a set of bots built around Left 4 Dead 2’s characters, but it never saw the light of day.)

Even recently, I’ve made a fun content-generation bot with CBDQ that spits out endless plots for pastiche John Le Carré novels. (My absolute favourite feature of that grammar is that a valid value for the $SURNAME option is $SURNAME-$SURNAME, meaning it’ll very occasionally spit out double-barrelled surnames, all thanks to the magic of recursion. I’ve only once ever seen it triple-barrel something).

Some of them stuck around; some of them died fast; some of them aged and I couldn’t fix them. But they all let me tickle particular itches. And, as I’d always imagined, they slotted themselves in alongside the burble of my friends and peers, little robot voice amidst the backchannel that floated in the top right of my screen. I enjoyed this, even knowing how this simple party-trick machines largely worked: most of my bots were just gags or toys folded into the stream of posts. I knew they weren’t sentient, weren’t “writing”, just assembling strings from probability. But they made the place feel different.

The writing was on the wall for quite a while. I remember when Tower Bridge disappeared. It turned out the username had been requested by the official exhibition, who according to the terms of use probably did have more of a claim to it than I. I was doing all this a long while before blue ticks, remember. I got the thing back up and running, but it wasn’t quite the same. Seven years ago, I could already see that I was not the type of user the platform was` looking to court.

The changes in August 2018 to the Twitter APIs meant that lots of interesting types of automated accounts just aren’t possible any more. Some have been taken down; other have withered. An art commission I worked on is now unable to function.

I hear about bots on Twitter in the news now, but it’s come to be a vernacular term for “automated accounts of foreign powers and agencies used for nefarious deeds” rather than “automatic content machines for charm and whimsy and art“. I understand why automatic content is most commonly equated with malicious action by platform owners – but I’m still allowed to miss a world that once was.

Every time I see a bot that’s doing new, or interesting, or unusual things, that raises a new smile, I am glad someone else is still doing this. Every time a creator like Darius or Allison announces they’re no longer working in the medium, I am at once saddened and entirely onboard with their reasoning.

twitter is a pretty bad website imo and they don't deserve the beautiful things we've made on their platform

— Allison Parrish | @aparrish@mastodon.social (@aparrish) July 24, 2018

Web 2.0 really, truly, is over. The public APIs, feeds to be consumed in a platform of your choice, services that had value beyond their own walls, mashups that merged content and services into new things… have all been replaced with heavyweight websites to ensure a consistent, single experience, no out-of-context content, and maximising the views of advertising. That’s it: back to single-serving websites for single-serving use cases.

A shame. A thing I had always loved about the internet was its juxtapositions, the way it supported so many use-cases all at once. At its heart, a fundamental one: it was a medium which you could both read and write to. From that flow others: it’s not only work and play that coexisted on it, but the real and the fictional; the useful and the useless; the human and the machine.

At the end of William Gibson’s Neuromancer, two AIs that are at the very boundary of legal capacity merge. (Fictional legal capacity, that is: Gibson imagines future laws that restrict the capabilities of AIs). They join, and disappear into the Cyberspace matrix, a new machine intelligence beyond what was previously possible. In Count Zero, set seven years later, new beings – the derivative fragments of that previous intelligence – roam Cyberspace freely, sometimes interacting with humans by manifesting as the Loa of voodoo, using us to achieve their goals and shape our reality.

A second plot device in the book involves tracking down the maker of a series of boxes that look a lot like Joseph Cornell’s work. They’re not Cornell pieces, though; they’re new, being made throughout the plot. In the end, their maker turns out to be another machine, working away in an old corporate space station, making boxes from its fractured dreams with commandeered manipulator arms.

That machine is the smartest of the machine sentiences in Cyberspace, and a ringleader for the others. But the Boxmaker has chosen not to engage with humans directly. Instead, it hides away, and makes art for itself.

As a response to the vastness of Cyberspace, that seems entirely reasonable to me.

In the real world, the terms and conditions have changed. It is 2018, and I miss being friends with a bridge. One age of Boxmakers is coming to an end; I’m most sad that they won’t be making any more boxes of their own.