I was, partly in jest, invited to join tourfilter by a friend today. What started as an elaborate social-networking joke turned into a really positive piece of user-experience I wanted to document.

What I wanted to share was the sign-up process. Normally, with social-networking sites, you have to endure some form of semi-elaborate sign-up before you’re allowed in… and then you start having to ram content in. Tourfilter neatly turns that on its head.

Tourfilter is a site that scrapes listings pages for information about your favourite bands, generating emails, RSS, or iCalendar files to keep you up-to-date. It’s a really simple, single-minded site that gives music fans personalised listings.

For a new user, there’s a form on the left of the homepage with a large textarea, in which you write the names of bands you like. I entered one band name… and via Ajax, a huge list appeared to the right of the field, of other bands I might like. Of course, I did, so I started clicking on some of them to add them to my form… and the process slowly became addictive. Pretty soon, I had a long list of bands I’d be potentially interested in seeing in London. The Ajax made it very compelling, and pretty quick. And, of course, the more bands I added, the more useful the fly-out Ajax list was, because it had better data to compare against.

Underneath the text box are three fields: username, password, and email address. Once you’ve filled them out, all you have to is click the submit button… and your brand new account is created, with all the information you’ve just filled out.

So tourfilter reverse the customary process: you add your initial data first, and only then create the account. Once you’ve done that, everything’s ready to go. I really enjoyed this experience: the Ajax element quickly showed the value of the site, which only increased the likelihood of me signing up.

I think tourfilter still has a little way to go – sometimes its scraping leaves something to be desired – but still felt its compelling sign-up process was worth commending.

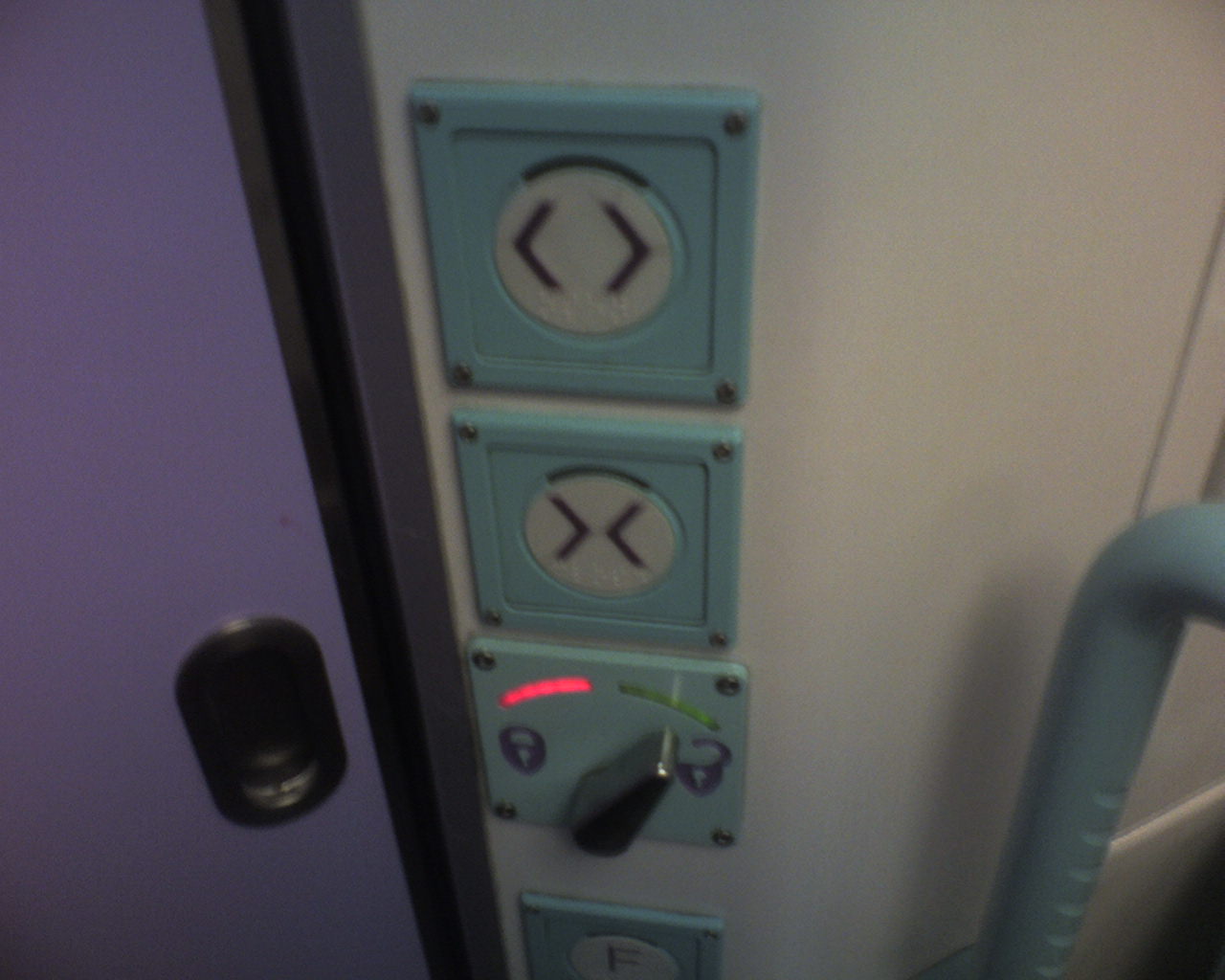

So imagine my surprise when, on the train home this morning, I found that the First Great Western toilets have been substantially modified (see left). At the top, open and close – and then a flick left/right switch for locking, with a red light for ‘lock’ and green for ‘unlocked’.

So imagine my surprise when, on the train home this morning, I found that the First Great Western toilets have been substantially modified (see left). At the top, open and close – and then a flick left/right switch for locking, with a red light for ‘lock’ and green for ‘unlocked’.