-

"Maybe participating in a Game Jam ought be a required rite of passage for anyone who wants to make videogames. It's a deep, oxygen-less dive into the depths of the industry, compressed into 48 hours. Survive it, and you can survive anything." Development as fractal.

-

"Smart things: the design of things that have computers in them, but are not computers". Mike Kuniavsky outlines the book he's currently working on. Looks interesting.

-

35mm, f1.8, crop-factor only, and with a built in motor so all the D40/D60 users can use it. This is big news – the first-party crop-factor prime. If they can make it super-affordable and good quality (at least as good as the 35mm f2 I'm thinking of buying) it's a lock.

-

"Whiskey Media provides fully structured data APIs for the following: Giant Bomb (games) Comic Vine (comics) Anime Vice (anime/manga)". This is a really good page for both explaining what you can and can't do, and explaining what the damn thing is. Wonder how good the data is?

-

"Have you ever wanted to sink your hooks into a gaming database full of release dates, artwork, games, platforms, and other sorts of related data? I'm going to guess that, for the bulk of you, the answer's probably no. But if you're out there wondering what to do next with your developer-savvy smarts, you've got another big source to pull data from. The Giant Bomb API is now available for non-commercial use." Giant Bomb really are doing some pretty interesting stuff, alongside their more traditional content.

-

"Customers seem to respond better to the Sims than all the adventure games ever made combined together. Then there are Bejeweled and Peggle and other game games. Who needs a stink’n story? I prefer making interactive stories." The writer of "Dangerous High School Girls in Trouble", interviewed on RPS, drops an interesting one.

-

"The baseline grid. Oh yes, the baseline grid. Let's be honest this is the sort of thing you know you need to know about. And you do know about, you know, sort of. But. Do you really know about it? Of course you do if you work on a magazine or a newspaper, but when was the last time you used one? I almost re-taught myself how to use a baseline grid. I certainly re-read all about it and it pretty much saved my life." Ben, on the details of The Paper. Good stuff in here.

-

"This is by no means an exhaustive list, just a start. In each of these you’ll find other resources to help you dig deeper." Which, right now, is what I need. For a former front-end-dev, I'm a bit behind the curve.

-

"So we’ve progressed now from having just a Registry key entry, to having an executable, to having a randomly-named executable, to having an executable which is shuffled around a little bit on each machine, to one that’s encrypted– really more just obfuscated– to an executable that doesn’t even run as an executable. It runs merely as a series of threads." Fascinating interview with a smart guy, who at one point in his life, did some bad (if not entirely unethical) work.

-

"I do think that during the coming years we will continue to try to bridge the gap between simulated musicianship and real musicianship. That said, the path there is not obvious: As the interactivity moves closer to real instrumental performance, the complexity/difficulty explodes rapidly. The challenge is to move along this axis in sufficiently tiny increments, so that the experience remains accessible and compelling for many millions of people. It’s a hard, hard problem. But that’s part of what makes it fun to work on." There is loads in this interview that is awesome; it was hard to choose a quotation. Rigopulos is super-smart.

-

"On June 17th, every year, the family goes through a private ritual: we photograph ourselves to stop, for a fleeting moment, the arrow of time passing by." Perfectly executed.

-

"The Bop It commands are called out in different tones. These tones differ from version to version as well. In Bop It Blast, distinct tones are employed by both male and female speakers." I did not know that.

-

"A couple of other examples of this kind of thing we like, are the bookish experimentations of B.S. Johnson, whose second novel Alberto Angelo contains both stream-of-conciousness marginalia, and cut-through pages enabling the reader to see ahead – possibly the most radical act I know in experimental books." Yes! And which I bang on about interminably. I love this stuff.

-

"A modern tale about caring, mending and letting-go, drawn with letters and punctuation marks." Oh! This is just beautiful – a short story about a girl, and a snail, composed entirely out of type.

-

"Not what I had in mind at all." George Oates on how her firing from Flickr played out, which was pretty horrific as it turned out – she was on the other side of the world, presenting on behalf of the firm. I am really not sure what Yahoo! hope to gain from many of their recent redundancies, and least of all this one.

-

"You want to hear some gluttons eternally force-fed cake and chocolate milk? I don’t know what else XBox Live microtransactions were made for, broseph. " Hardcasual, I love you.

-

"Herzog Zwei was a lot of fun, but I have to say the other inspiration for Dune II was the Mac software interface. The whole design/interface dynamics of mouse clicking and selecting desktop items got me thinking, ‘Why not allow the same inside the game environment? Why not a context-sensitive playfield? To hell with all these hot keys, to hell with keyboard as the primary means of manipulating the game!" Brett Sperry, of Westwood, on the making of Dune II. Via Offworld.

-

"Changing the Game (order via Amazon or B&N) is a fast-paced tour of the many ways in which games, already an influential part of millions of people’s lives, have become a profoundly important part of the business world. From connecting with customers, to attracting and training employees, to developing new products and spurring innovation, games have introduced a new level of fun and engagement to the workplace.

Changing the Game introduces you to the ways in which games are being used to enhance productivity at Microsoft, increase profits at Burger King, and raise employee loyalty at Sun Microsystems, among other remarkable examples. It is proof that work not only can be fun–it should be." I shall have to check this out.

-

"As a result, vendors here are more likely to decline to sell you something than to cough up any of their increasingly precious coins in change. I've tried to buy a 2-peso candy bar with a 5-peso note only to be refused, suggesting that the 2-peso sale is worth less to the vendor than the 1-peso coin he would be forced to give me in change." They're running out of coins in Argentina, and it makes for a seriously odd situation – and a reminder of the differences between value and worth.

-

"The artist Keith Tyson is offering 5,000 Guardian readers the opportunity to own a free downloadable artwork by him. The costs you'll have to bear are those of printing out the work on A3 photographic paper – and framing, if you so choose… You will be asked to enter your geographical location – which forms part of the unique title of each print."

-

"The media would have us believe that those with the best ability in Parkour require and condition to bodies of hypermasculine levels, and the first notions of this concept seem quite logical. However, it is known to any traceur that the spectacle of the masculinized body is not in necessary relation to one’s ability of movement. Mass media tries to paint another picture with a careful selection of handsome, muscular men as traceurs… At its simplest, the hypermasculine spectacle is an easier sell to masses. However, our problem does not end at the body. It is not only the body that is masculinized, though, as we see the same pattern occurring to the discipline itself." Interesting article on Parkour and gender; specifically, the hyper-masculinisation of the art by the media.

-

"Over three years ago I set a goal for myself. That goal was to have a max level character for every class in the game… Tonight, at long last, I’ve finally achieved my goal." Blimey.

-

"As editorial director of Ladybird Books, Douglas Keen, who has died aged 95, was responsible for the first experience of reading of millions of children." Myself included; I learned to read with Peter, Jane, and my Mum, sitting on my bedroom floor each morning.

-

Amazingly, a few in here I didn't know – "move selection" and "delete only whitespace" for starters.

-

"I call this new form "procedural rhetoric," a type of rhetoric tied to the core affordances of computers: running processes and executing rule-based symbolic manipulation. Covering both commercial and non-commercial games from the earliest arcade games through contemporaty titles, I look at three areas in which videogame persuasion has already taken form and shows considerable potential: politics, advertising, and education. The book reflects both theoretical and game-design goals." Add to cart.

-

"I won’t rant about how our tax dollars pay for these images and how we deserve better. But what I do find alarming is that these documents are used to brief major decision makers. These decision makers may know a thing or two about policy and politics, but if decoding and understanding the armed forces budget is the goal of these documents, then there is a huge failure here." Datafail and slidecrime, all under one roof.

-

"The true orator is one whose practice of citizenship embodies a civic ideal – whose rhetoric, far from empty, is the deliberate, rational, careful organiser of ideas and argument that propels the state forward safely and wisely. This is clearly what Obama, too, is aiming to embody: his project is to unite rhetoric, thought and action in a new politics that eschews narrow bipartisanship. Can Obama's words translate into deeds?" Nice article on rhetoric and oratory. Cicero really is quite the writer, you know; ages since I've read him, but this brings it all back.

-

"When the mechanics are broken there – no matter what great ingredients or designs you had – the dish disappoints. Execution is very much part of the analysis there – as is service, mis-en-scene. Food is never evluated (in the Guide Micheline sense) out of context… but the mechanics are fundamental to everything else." Robin Hunicke on another parallel to games criticism; I think she might be onto something, and it's another good contribution to the mound of Mirrors' Edge coverage.

-

"Though few gamers might be interested in long haul trucking, there is nothing wrong with concentrating on a small group of gamers and offering them the best experience they can get within their limited requirements. In fact, the more MMO developers who realize this—that a small group of loyal players is better than a huge group of disinterested players—the better, honestly." Very true – a nice conclusion to Matthew Kumar's round-up of a somewhat niche – but interesting sounding – browser MMO.

-

"The moisturiser, far from the trusted friend and counsellor of the first reading, is The Picture of Dorian Gray." Alex tries to read that Nivea ad that's all over stations right now. It is confusing.

-

"We think it's one of the greatest inventions of the twentieth century." Awesome. This is why kids go into engineering.

-

"Maps, databases and other resources that help you dig deeper." A shame the raw data isn't available, but great they're collating this stuff and seeing it as another channel of news they provide.

-

"A favorite on college Unix systems in the early to mid-1980s, Rogue popularized the dungeon crawling computer game dating back from 1980 (and spawned entire class of derivatives known collectively as "roguelikes"). gandreas software now presents the classic for the iPhone/iPod Touch." Oh god, Rogue for the iPhone. Unusual gestural interface, but it's a perfect port, and brings back memories of being 7 all over again. Needless to say, I installed it immediately.

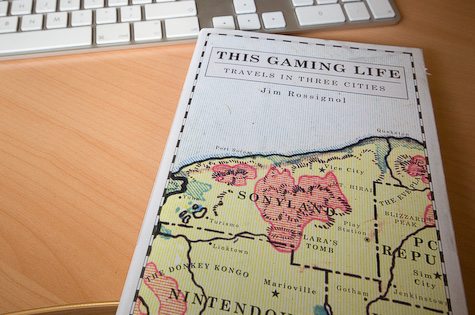

Blog All Dog-eared Pages: This Gaming Life, by Jim Rossignol

10 November 2008

One of the books I read on my holiday in Pembrokeshire was Jim Rossignol‘s This Gaming Life. I’d been meaning to get around to it for quite a while, and finally did so once it was revealed that the (beautiful) hardback edition was nearly at the end of its print run.

It’s an interesting book, if perhaps somewhat flawed. This Gaming Life is games writing filtered through the lens of travel writing; the “three cities” of the title being London, Seoul, and Rekjavik. “London” feels a little weak, and disjointed; the focus on Splash Damage is reasonably strong, but is perhaps not connected enough horizontally. It is also a reminder of the book’s strong leaning (understandably, given Rossignol’s expertise) towards PC gaming. As a result, certain PC-centric aspects of games such as modding cultures are praised perhaps a tad more highly than I think is reasonably within the bounds the text sets itself.

Seoul is more interesting, if only because it’s much more alien to most readers. There’s some strong insights and good anecdotes here, and it stands alongside Rossignol’s original PC Gamer article on gaming in Korea well (available in PDF form here).

The strongest section of the book is the final half, which is set in Rekjavik and focuses on CCP and their massive online game EVE Online. Rossignol is well versed in EVE and a keen player of the game, and it really shows – there are so many good stories, personal anecdotes combined with objective criticism, that the book leaps to life in this section. Part of me would love to have seen the other two thirds as long, and as strong, as this; the other part of me would love to see Rossignol just drop 300 pages on EVE, because it’s obvious he could, and it’d be an essential piece of criticism and historiography. Maybe that’s on the way.

But, despite its flaws and occasional ponderous prose, I really liked the book. There’s lots of good stuff in here, and I was pleased with the notes I came away with (see below).

It feels a little out of place in a book so fixated on PC gaming, but the “playlist” Rossignol provides at the end of the book is fantastic: a list of games that, whilst obviously never going to be conclusive, represent a good way into games for the uninformed. His selection is strong, and his writing about each of the titles is joyful and unpretentious; most of them require either a PS2 or a PC, and I can hardly argue about many. It’s nice that it’s there, even if only as a reminder, at the end of the book, that all the writing in the world won’t matter if you don’t play the damn things.

Most of all, though, I’m just glad books like this can exist. It’s published through the MIT Press University of Michigan, and I really hope it sets the scene for more writing on games like this. It’s grown-up, personal but not gonzo, multi-disciplinary and prefers rational, informed, and sometimes unresolved discussion over snap judgments and pithy soundbites. This, to my mind, is a format that suits games writing (not just criticism) incredibly well, and I hope that UMICH Press (and their competitors) seek to comission and publish more work like this, because it’s important that games starts to establish a second-order culture of criticism as well as a first-order culture of play.

I feel like I’m being harsh on the book earlier, but really, that’s just because it’s an early entry in this space, and it’s for that it needs to be praised. I have no doubt that Rossignol has even more – and even better – writing to come, and I’m looking forward to it eagerly. In conclusion: definitely recommended, but with what I think are reasonable reservations. Also, the less-well versed you are in some of the topics he discusses, the more essential a purchase I think it might be; perhaps my reservations are coming from someone too deep inside the topics he discusses.

As is traditional in such threads, here come the quotations that I found, for whatever reason, worth turning a corner over near:

p.30, on boredom:

“use of the term boredom has increased ceaselessly since the eighteenth century. It cannot be found in English before 1760, and although [Lars] Svendsen notes that some European languages came up with equivalent words in the centuries before, they were generally derivations of the Latin for “hate” and carried similar meanings”

p.43, on some of the motivations for writing the book:

“My travels had begun to reveal that almost all writing and reporting concerned with gaming overlooked what the experience of gaming had meant to the gamers themselves. There was some talk about the intellectual or cognitive experience, but how games slotted into different lives and how they changed perceptions and agendas was being ignored”

p.52, Leo Tan talking about playing Guitar Hero at the Donnington Rock Festival:

“…playing Guitar Hero on stage is a completely different experience to playing at home. At home, you might feel like a guitar god; but on stage, people are screaming, and when you come off, they swamp to the sides to try to talk to you. It’s exhilarating in a way that I’ll never experience elsewhere. And it was a game. And everyone knew it was a game.”

p.73, on televised pro gaming:

“gaming remains and awkward spectator sport. It’s an interesting avenue of possibility for a small clique of gamers, perhaps; but the low number of people who watch video games played by the pros outside Korea suggest that the most important aspect of gaming is its interactivity. I’ve seldom been as bored as I have been watching pro gaming tournaments, especially when they’re for a game I’m actually interested in playing. For these reasons, I believe that Korea’s televised Star-leagues reflect a cultural singularity within Korea, not an indication of where global gaming will go in the future.”

p.76, on the real-world communities and companionships forged through online gaming:

“Thanks to games, [Lee] In Sook [a high-level Lineage II player]’s circle of friends had ended up talking, becoming close, and then making sure that they hung out at the same cafés to play at the game games. Online games create shared experiences that are unlike those we might have in the real world. This is a quality of the medium itself – players who might not excel in conversation might feel confident in text chat.”

p.77, on the nature of those communities forged within games:

“Online games are usually far more like teeming cosmopolitan cities than stable provincial communities: the mix of people is enormously diverse, and you often find yourself being ignored by passersby or even accosted with unsettling propositions. You aren’t sure who to trust, and many gamers will depend on previous acquaintances or real-world friendships as the basis for in-game socializing.”

p79:

“Games stand to change not simply individual imaginations or personal finances but the possibilities for interaction and socialization across our different cultures. This is no grand cultural revolution: it is a subtle wave, a gradual tectonic shift in the way we live, which will only make its true effects known over the course of many years… chasing headlines that read ‘Games Are The New Sport’ or ‘Kids Who Play Games For A Living’ makes a crude statement about what really matters within gaming. The important changes will come from those smaller ripples that change how millions of people live, think, and socialize on a daily basis, not just the hard-core niches.”

p.93, on how games manipulate and inspire our imaginations:

“The in-game slaughter of the attendees of a funeral held for a deceased World of Warcraft player presented a case of quite spectacular insensitivity. It revealed a significant swathe of gamers who radically failed to sympathize with their fellow gamers, treating them as little more than moving targets and ignoring the real-life tragedy they were trampling on. Perhaps, however, they were simply acting within the narrative conventions that the game delivered to them. Their game belonged firmly within the genre of bad guys versus good, and they played the bad guys. Had it been a game about tragedy and human loss, the gamers’ responses and actions might have taken on quite a different character.”

p.100, quoting Kieron Gillen on simulation:

“‘Battlefield 2 presents a beleaguered United States in a war that is more cowboys and Indians than anything else, while Operation Flashpoint reaches for something more akin to a comment on the nature of war using theoretical examples’… as Gillen observes, ‘simulation is expression'”

p.102, leading into discussion of Luis von Ahn and his ESP game:

“Game creators don’t have to speak to gamers at all, nor do they necessarily have to persuade them of anything. It is simply by letting gamers get on with playing that they really begin to change the world. To me, this idea is one that seems far more radical than molding games into old-fashioned propaganda: it is the notion of using games for the purposes of ‘human computing'”

p.106, on one kind of propaganda present in games:

“The danger of games, [Chris] Suellentrop suggests, is that they teach us that success means discovering and then following the rules – a deeper genre of propaganda. If he’s right, then the ever-growing millions of obsessed gamers could eventually be playing their way into a new and subtle kind of oppression, something far more worrying than finding their ‘wasted cycles’ put to use in the technology of a major corporation’s search engine.”

p.145, on “use models”:

“Will Wright observed that unless you actually play games, it’s hard to judge what is happening to a gamer. ‘Watching someone play a game is a different experience than actually holding the controller and playing it yourself. Vastly different. Imagine that all you knew about movies was gleaned through observing the audience in a theatre – but you had never watched a film. You would conclude that movies induce lethargy and junk food binges. That maybe true, but you’re missing the big picture.'(Wired, April 2006)”

p.147, more Will Wright (from a conversation with Brian Eno):

“When we do these computer models, those aren’t the real models; the real models are in the gamer’s head. The computer game is just a compiler for that mental model in the player. We have this ability as humans to build these fairly elaborate models in our imaginations, and the process of play is the process of pushing against reality, building a model, refining a model by looking at the results of looking at interacting with things.”

p.150, applying Wright’s model to EVE Online:

“EVE is a shared mental model in the heads of both thousands of gamers and dozens of developers, with a process of feedback moving cyclically between all those involved. The mental model is not htat of one person engaging with a singl emodel on a personal screen, but a picture comprised of tens of thousands impressions of the same model… [EVE] is a single collaborative imaginative enterprise that exists in real time… those who have had time [to sink into playing and exploring EVE] have begun to uncover something remarkable and one of the possible future directions for gaming: entertainment that is also massive collaboration.”

p.170, on LittleBigPlanet (which, at the time of writing, was still in production). I particularly liked this simple turn of phrase:

“LittleBigPlanet presents games as malleable, communicable objects, built for gamers to customize and distort as they see fit.”

“Communicable objects” seems about right.

p.171, on Tringo:

“Tringo had become a leaky object: moving between physical and virtual realities seamlessly. It was a virtual entity that had become a physcial product, while still making money within a virtual world.”

Again, “leaky object” is very good.

p.181, quoting Julian Dibbell:

“Dibbell makes a powerful case for the contemporary social and political importance of virtual interactions, as well as summing up something about thei weird, hybrid nature as both games and monetary systems: ‘Games attract us with their very lack of consequence,’ Dibbell wrote in Wired magazine, ‘wheras economies confront us with the least trivial pursuit of all, the pursuit of happiness.”

p.183, on the shape of online gaming groups such as clans or guilds:

“…it seems that they are becoming more like actual communities or tribes. Like entertainment-seeking nomads, they move from one game to the next. If the future of games ends up being focused on user-generated works, then we will probably join projects because we like gaming with particular people we have met elsewhere. We might like the look of what they are making or how they are influencing the game world they plkay in, but it’ll be the gmaers themselves that reinforce our commitment or define how our gaming is experienced.”

p.192, on what might be described as the journalist’s dilemma:

“I am caught between my personal interest in the games and the gamers who play them, on the one hand, and the billion-dollar business machine for which I have become a regular mouthpiece, on the other. I am troubled by the idea that games have to have some greater purpose than entertainment, and yet I am enthralled by the idea that they cabn be used as propaganda, art, or medicine. I want to spend all my time exploring the peculiar physics of a new game world, and yet I am compelled to write about and describe it for money.”

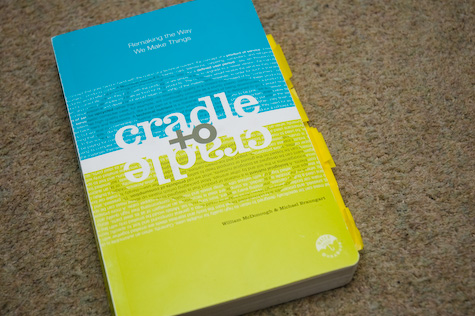

Blog all dog-eared pages: “Cradle to Cradle”

23 March 2008

Any way you look at it, William McDonough and Michael Braungart’s Cradle to Cradle is an unusual book.

It’s a book that invites the reader to envisage a world in which the concept of waste does not exist, and where re-use is preferred to recycling; in short, a world where products have a true life-cycle, rather than a passage from cradle-to-grave.

It’s an exciting book, if only because the physical artefact embodies its message:

Cradle to Cradle is not made out of paper, you see. It’s a format called Durabook. The Durabook is made of a kind of plastic, and is entirely waterproof. More interestingly, it’s entirely reusable – the ink can be easily removed to allow reprinting or notebook use, and the “paper” itself can be melted down and reused without giving off toxins. It’s a good environmental citizen, essentially: reusable, up-cyclable, and with no harmful byproducts. (It’s also surprisingly heavy for such a slim format).

I found it an interesting read. I found a lot of their later commentary on designing services probably the most interesting and relevant – a lot of discussion on refactoring products (which, by their nature, are designed for disposal) into services (wherein the product can be upcycled or removed from the equation, as it’s the service that matters). The Linc concept mobile phone is a good illustration of the thinking the book suggests.

At times, though, I found it depressing; a lot of the innovations pointed to are McDonough and Braungart’s own, and it would have been good to see more examples from people other than them. Similarly, at times the scale of the challenges described in the book seems colossal, and perhaps impossible.

But I think, taken with a pinch of salt, it’s an interesting read, and there’s some good meat within it. With that in mind, here’s what I marked out for myself as being interesting:

p.24, on Henry Ford’s innovations:

“In 1914, when the prevailing salary for factory workers was $2.34 a day, he hiked it to $5, pointing out that cars cannot buy cars. (He also reduced the hours of the workday from nine to eight). In one fell swoop, he actually created his own market, and raised the bar for the entire world of industry.”

I really enjoyed the section on Ford. They point out that a lot of Ford’s innovations really were more environmentally-friendly than the wasteful, inefficient factories that had preceded them. This doesn’t make it good, per se, but it’s worth bearing in mind. And I love “cars cannot buy cars”.

p.46, on the sentiments of the American Pastoral writers:

“[Aldo] Leopold anticipated some of the feelings of guilt that characterise much environmentalism today:

“When I submit these thoughts to a printing press, I am helping cut down the woods. When I pour cream in my coffee, I am helping to drain a marsh for cows to graze, and to exterminate the birds of Brazil. When I go birding or hunting in my Ford, I am devastating an oil field, and re-electing an imperialist to get me rubber. Nay more: when I father more than two children I am creating an insatiable need for more printing presses, more cows, more coffee, more oil, to supply which more birds, more trees, and more flowers will either be killed or … evicted from their several environments.”

p.60, on the struggle between what Jane Jacobs described as commerce and the guardian:

“Any hybrid of these two syndromes Jacobs characterizes as so riddled with problems as to be ‘monstrous’. Money, the tool of commerce, will corrupt the guardian. Regulation, the tool of the guardian, will slow down commerce.”

p.61, on regulation being a signal of design failure:

“In a world where designs are unintelligent and destructive, regulations can reduce immediate deleterious effects. But ultmiately a regulation is a signal of design failure. In fact, it is what we call a license to harm: a permit issued by a government to an industry so that it may dispense sickness, destruction, and death at an ‘acceptable’ rate.”

p.66-67, on sacrifice and “eco-efficiency” as a way of trying to cut down on the bad things humans do:

“In very early societies, repentance, atonement, and sacrifice were typical reactions to complex systems, like nature, over which people felt they had little control. Societies around the world developed belief systems based on myth in which bad weather, famine, or disease meant one had displeased the gods, and sacrifices were a way to appease them…

But to be less bad is to accept things as they are, to believe that poorly designed, dishonorable, destructive systems are the best humans can do. This is the ultimate failure of the ‘be less bad’ approach: a failure of the imagination. From our perspective, this is a depressing vision of our species’ role in the world.

What about an entirely different model? What would it mean to be 100 percent good?”

It takes them a while to get to that point (in a ~180 page book), but that’s the real kicking-off point for the more interesting arguments – by reframing the problem in a world that doesn’t have a concept of waste, what kind of answers emerge?

p.70, on rethinking the “entire concept of a book” (which is something the artefact of Cradle to Cradle itself does, as mentioned earlier):

“We might begin by considering whether paper itself is a proper vehicle for reading matter. Is it fitting to write our history on the skin of fish with the blood of bears, to echo writer Margaret Attwood?”

p.80, on “nature’s services”:

“Some people use the term nature’s services to refer to the processes by which, without human help, water and air are purified […] We don’t like this focus on services, since nature does not do any of these things just to serve people.”

True “services” have to intend to service a particular need – you can’t just apply the s-word to any available substrate or process.

p.84:

“Western civilization in particular has been shaped by the belief that it is the right and duty of human beings to shape nature to better ends; as Francis Bacon put it, ‘Nature being known, it may be master’d, managed, and used in the services of human life.‘”

p.87, on new approaches to zoning:

“We agree that it is important to leave some natural places to thrive on their own, without undue human interference or habitation. But we also believe that industry can be so safe, effective, enriching, and intelligent that it need not be fenced off from other human activity. (This could stand the concept of zoning on its head; when manufacturing is no longer dangerous, commercial and residentail sites can exist alongside factories, to their mutual benefit and delight.)”

That would make Sim City interesting.

p.88; professor Kai Lee talks to members of the Yakima Indian Nation about the long-term plans for storing nuclear waste within their territory.

“The Yakima were surprised – even amused – at Kai’s concern of their descendants’ safety. ‘Don’t worry,’ they assured him. ‘We’ll tell them where it is.’ As Kai pointed out to us, ‘their conception of themselves and their place was not historical, as mine was, but eternal. This would always be their land. They would warn others not to mess with the wastes we’d left.

We are not leaving this land either, and we will begin to become native to it when we recognize this fact.”

This reminds of Tom Coates’ Native to a Web of Data – we will become native to the web when we recognise that the data structures we create and impose on it will stick around forever, and that we should design them as such.

p.102, on “deflowering” a new product:

“Opening a new product is a kind of metaphorical defloration: ‘This virgin product is mine, for the very first time. When I am finished with it (special, unique person that I am), everyone is. It is history.’ Industries design and plan according to this mind-set.”

p.103:

“What would have happened, we sometimes wonder, if the Industrial Revolution had taken place in societies that emphasize the community over the individual, and where people believed not in a cradle-to-grave life cycle but in reincarnation?”

p.104, describing the two discrete metabolisms of the planet:

“Products can be composed either of materials that biodegrade and become food for biological cycles, or of technical materials that stay in closed-loop technical cycles, in which they continually circulate as valuable nutrients for industry. In order for these two metabolisms to remain healthy, valuable, and successful, great care mus be taken to avoid contaminating one with the other.”

p.120: fittest vs fitting-est

“Popular wisdom holds that the fittest survive, the strongest, leanest, largest – perhaps meanest – whatever beats the competition. But in healthy, thriving natural systems it is actually the fitting-est who thrive. Fitting-est implies an energetic and material engagement with place, and an interdependent relationship to it.”

p.128, on misunderstanding Le Corbusier’s intent:

“Modern homes, buildings, and factories, even whole cities, are so closed off from natural energy flows that they are virtual steamships. It was Le Corbusier who said the house was a machine for living in, and he glorified steamships, along with airplanes, cars, and grain elevators. In point of fact, the buildings he designed had cross-ventilation and other people-friendly elements, but as his message was taken up by the modern movement, it evolved into a machinelike sameness of design.”

p.144, on people’s affinity for certain types of visual:

“According to visual preference surveys, most people see culturally distinctive communities as desirable environments in which to live. When they are shown fast-food restaurants or generic-looking buildings, they score the images very low. They prefer quaint New England streets to modern suburbs, even though they may live in developments that destroyed the Main Streets in their very own hometowns. When given the opportunity, people choose something other than that which they are typically offered in most one-size-fits-all designs: the strip, the subdivision, the mall. People want diversity because it brings them pleasure and delight. They want a world of [paraphrasing Charles De Gaulle] four hundred cheeses.”

p.154, on criteria for new product design:

“High on our own lists [of criteria] is fun: Is this product a pleasure, not only to use, but to discard? Once, in a conversation with Michael Dell, founder of Dell Computers, Bill observed that the elements we add to the basic business criteria of cost, performance, and aesthetics – ecological intelligence, justice, and fun – correspond to Thomas Jefferson’s ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’. Yes, Dell responded, but noted we had left out a most important consideration: bandwidth.”

p.172, on the aspects of marketing and selling eco-friendly products:

“A small but significant number o consumers chose to buy the lotion in a highly unattractive ‘eco’ package shelved next to the identical product in its regular package, but the number who chose the ‘eco’ package skyrocketed when it was placed next to an over-the-top ‘luxury’ package for the very same product. People like the idea of buying something that makes them feel special and smart, and they recoil from products that make them feel crass and unintelligent. These complex motivations give manufacturers power to use for good and for ill. We are wise to beware of our own motivations when choosing materials, and we also can look for materials whose ‘advertising’ matches their insides, again as indicative of a broader commitment to the issues that concern us.”

p.185, in a section on “preparing for the learning curve”:

“Biologist Stephen Jay Gould has captured this concept nicely in a way that can be useful to industry: ‘All biological structures (at all scales from genes to organs) maintain a capacity for massive redundancy – that is, for building more stuff or information than minimally needed to maintain an adaptation. The ‘extra’ material then becomes available for constructing evolutionary novelties because enough remains to perform the original, and still necessary, function’. Form follows evolution.”

And that’s all, really. I enjoyed it a lot – though I found its message difficult and overfacing at times, and the perspective perhaps a little smug, there was lots of good stuff in it and it provided food for thought. Thanks to Tom for letting me borrow it, and to Mike for the format this blogpost takes.

Blog all dog-eared pages: Joe Moran, Reading the Everyday

17 February 2008

I acquired Reading the Everyday from work several years ago, and only recently got around to reading it, in part after Alex’s hugely enthusiastic feedback. It turned out to be a wonderful read. I’m not particularly well-versed in cultural studies, so much of the French work Moran refers to is somewhat new to me. It is, however, fascinating to see such a uniquely British study of the everyday; just as the French ideals of le quotidien are very much rooted in 50s France – and the Parisian suburbs especially – so Moran focuses on a Britain that developed in the 60s, 70s, and 80s, through the booming newtowns into Thatcherism.

The book gets especially good as it moves out of criticism of theory and into more focused case-studies, on everything from bus-shelter advertising and queuing to the M25 and traffic lights. Anyhow, enough rambling. On with the quotations, from dog-eared pages, or (more often) just stuff I underlined. It’s been a while since I read a book with a pencil so vigorously in hand!

p.3:

“It is hard to stand at a bus stop, as the single-occupant cars stream by, without feeling somehow denied full membership of society”

p.7:

“Henri Lefebvre suggests that everyday life is increasingly made up of this ‘compulsive time’, a kind of limbo between work and leisure in which no explicit demands are made on us but we are still trapped by the necessity of waiting.”

p.47, on the final episode of The Office:

“It is about the forgetfulness of office life, the way that its impersonal procedures do not acknowledge the finite trajectory of individual lives, despite the leaving dos and retirement parties that lamely suggest otherwise.”

p,65, in a wonderful section all about the Westway:

“In truth, the Westway provokes conflicted emotions, commensurate with our cultural confusion about the relationship between the individual freedom of driving and the collective horror of traffic congestion.”

p.86, on how we read images from CCTV cameras:

“The telltale digits in the corner of the screen revealing the date and time convey not the reality of round-the-clock surveillance but the specific moment at which an extraordinary event happened or was about to happen.”

p.98, on motorways as an example of what Marc Augé called “non-places”:

“The importance of the road sign in the non-place, for Augé, is that it allows places to be cursorily acknowledged without actually being passed through or even formally identified.”

p.101, quoting Chris Petit’s commentary on his film “London Orbital”:

“[the M25 is] mainline boredom, a quest for transcendental boredom, a state that offers nothing except itself, resisting any promise of breakthrough or story. The road becomes a tunnelled landscape, a perfect kind of amnesia.”

and later in that page, on Iain Sinclair’s book of the same name:

“Sinclair notes that in the nineteenth century, the area now occupied by the M25 housed mental hospitals and sanatoriums, and represented the safe distance to which Victorians would remove contaminated parts of the city.”

p.108, in a section on service stations:

“When they first opened, young people would drive to the service stations at high speeds to play pinball, drink coffee and eat ice cream, as a more alluring alternative to the only other all-night venue, the launderette.”

I never thought of that – launderettes as the only mainstream 24-hour venue in the provinces. Like so much of the book – a great wake-up call.

p.132, in the chapter on “Living Space”, Judy Attfield offers commentary on home makeover shows like Changing Rooms:

“…such shows elevate a notion of design, which she defines as ‘things with attitude’, over the banal reality of material culture, which she calls ‘design in the lower case’.”

Totally. I loved this distinction – the idea that things with attitude, so valued at the temporary level (a cool thing in a shop, the first five minutes of staring at a made-over room) are not necessarily the things we want to spend long periods of time with.

p.145, quoting Paul Barker on ‘Barratt’s transformation of Britain’s vernacular landscape’:

“When the social history of our times comes to be written, he [Lawrie Barratt, the company’s founder] will get more space than Norman Foster. You can search out Foster masterpieces here and there. But Barratt houses are everywhere. Foster buildings are the Concordes of architecture. Barratt houses fly charter.”

p.157, on Moran’s trip to Chafford Hundred, a new housing-estate-cum-new-village in Essex:

“Walking around Chafford Hundred, it is not long before I am completely lost – partly because the sameness of the houses provides no landmark, and partly because the curvilinear streets are disorientating. Invented in American tract developments to close off the vista and protect the viewer from the unwelcome sight of an endless row of subdivisions, the curvilinear street has the unfortunate side effect of destroying any sense of direction… getting lost in Chafford Hundred seems like a metaphor for housebuilding as a political black hole.”

p.161:

“In a note to its clients, [investment bank] Durlacher observed: ‘Probably the best indication of difficulties in the market will be when Property Ladder is no longer commissioned”

p.164, on the design of the Trabant:

“Its accelerator pedal even had a point of resistance part of the way down to discourage excessive fuel consumption.”

Moran points out that everything about the Trabi was counter to the traditional “counternarratives of speed, status and freedom” that cars espouse in the Western world, but I love the idea of the values of a society and culture being literally built into the products it produces; the socially-responsible accelerator pedal feels like a very good example of that.

p.167, on the problematic aspects of “mourning and coping narratives” in a post-9/11 world:

“…they confront us with and ‘ordinary life’ whose normality is never questioned. It is more difficult to make a similar imaginative connection with Iraqis or Afghans killed by bombs dropped from fighter planes, because their daily lives are not so easily recognizable or represented.”

Moran talks a lot about the dangerous ideals of “ordinary life” and “ordinary people” in his books – concepts we know are very dangerous in the concept of design. The idea that their are specifivites in our understand of the everyday that do not map elsewhere is a very important one, and a reminder that if anything is presented of foreign culture in the media – especially the news media – it is rarely the truly “everyday”.

More on that further down the page:

“Richard Johnson points out that the term ‘way of life’, which has a particular resonance in cultural studies and was constantly reiterated by politicians such as Tony Blair and George Bush in the months after September 11, ‘resists instant and “fundamentalist” moral (or aesthetic) claims to superiority without letting go of evaluation entirely’. It conflates ‘the necessary sustaining practices of daily living and the more particularly “cultural” features – systems of meaning, forms of identity and psycho-social processes – through which a world is subjectively produced as meaningful'”

p.169 – the final page, and a wonderful quotation from Henri Lefebvre to conclude these notes:

“Man must be everyday, or he will not be at all.”

A great book, then. There’s masses in it about ideas of mundanity and the everyday, and I got a lot out of it from a design perspective, particularly. It also looks like it will overlap with Adam Greenfield’s “The City Is Here For You To Use” quite nicely. Highly recommended!

Book Review: David Black’s Ruby for Rails

04 August 2006

Didn’t notice this when it happened (because it didn’t necessarily appear on the frontpage) but… my review of David Black’s Ruby for Rails has now gone live over at Vitamin.

My first piece of technical writing. It’s a good book, too – clarified an awful lot about the hierachy of classes within the language, and explained the nuances of Ruby dynamism very well; strongly recommended to anyone coming to Ruby (through Rails) afresh, whether you’re an experienced programmer or not. I hope I conveyed that in the review.