The other night, Matt was showing me his newly unlocked iPod Touch. I was playing with the shell application – just poking around, running top, etc – and rotated the iPod onto its side, just to see if the screen-rotation stuff worked in the third-party application.

After a while, Matt picked up what I was doing – as I poked around, when I found an app that felt like it should have a horizontal view, I would tip the iPod over, wait a second, and then tip it back.

It reminds me of a running joke my parents had with me ever since I was little. I used to pick up Christmas presents and shake them, and if they rattled, I’d assume that they were Lego (Lego, at the time, being the only kind of present I got that rattled). Ever since, we’ve always joked that rattling presents are Lego. And just like I rattled presents to see if they had the potential to be Lego, so you “rattle” the iPod to see if an application has the potential to be rotated.

You don’t necessarily need a visual signpost (an icon or alert) that such functionality is available; you just rotate the device, wait a second, and then flip it back. As a user, you’re interrogating the user to see if that particular interaction is possible. Is that good design? In some kinds of interaction, I don’t think so; you don’t want to poke every button or crawl through every menu just to find out what is or isn’t possible.

With the iPod/iPhone, though, we’re not crawling menus; we’re just interrogating the device to see if it supports a single kind of interaction. We only want a true or false back from it. Couple that boolean response with the simplicity of the accelerometer interface, and these “rattling” interactions come at a much lower cost.

I like rattling as a metaphor for this kind of interaction; it’s the equivalent of responds_to? in Ruby, I guess. What are other good examples of rattling-type interactions I’m missing? And how good are the implementations of it in software or on the web?

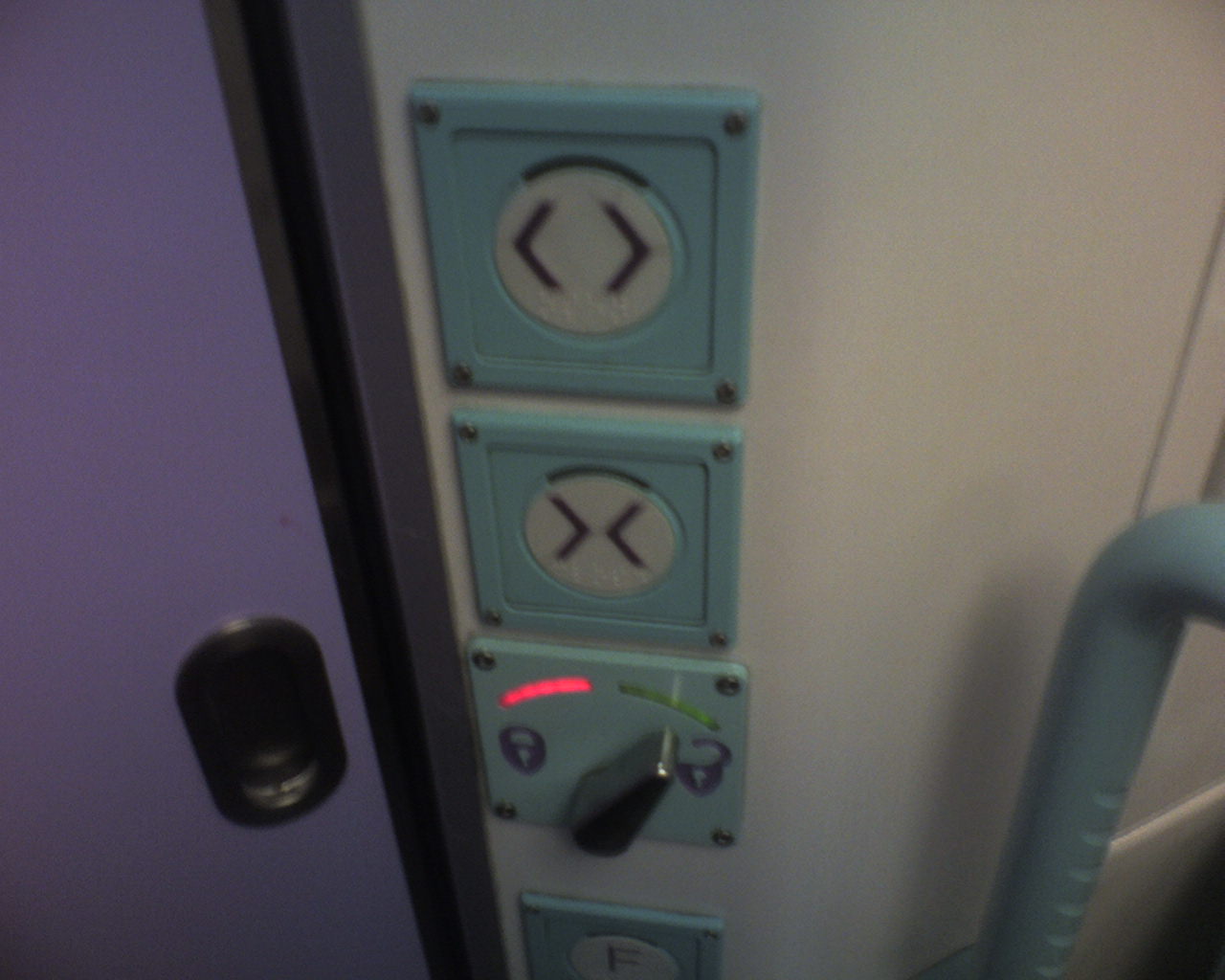

So imagine my surprise when, on the train home this morning, I found that the First Great Western toilets have been substantially modified (see left). At the top, open and close – and then a flick left/right switch for locking, with a red light for ‘lock’ and green for ‘unlocked’.

So imagine my surprise when, on the train home this morning, I found that the First Great Western toilets have been substantially modified (see left). At the top, open and close – and then a flick left/right switch for locking, with a red light for ‘lock’ and green for ‘unlocked’.