-

"However, if you are making a sustainable living doing pay-up-front games, and you find those are the kinds of games you are most passionate about, but you feel the itch to try out free-to-play because some other people are getting rich doing it, then I'd take a step back and examine your motives and what makes you fulfilled as a person. VC-types look down on this kind of thinking with the awesomely cynical term "lifestyle business", but isn't that exactly what we want to create, a business that supports our desired lifestyle, which includes making games we're proud of?" Chris Hecker on Free-to-Play

-

"Patient explained most of these (and most subsequent) injuries as being the result of membership in a private and apparently quite intense mixed martial arts club. Patient has denied being the victim of domestic abuse by Mr. Grayson following indirect and direct questioning on numerous occasions." Patient BW's medical records make for iiinteresting reading.

-

"…the world of Shadow of the Colossus is seemingly empty, except for the colossi and the warrior. Until you reach a colossus, there is no music, leaving you alone with your thoughts and the sound of your horse’s hooves. No enemies jump out to attack, it occurred to me on one of these rides, because I am the one on the hunt. The natural order of a video game is reversed. There are no enemies because I am the enemy." A decent enough piece on Ueda's games for the New Yorker – but this paragraph is marvellous.

-

"Are we really going to accept an Interface Of The Future that is less expressive than a sandwich?" Yes, good.

-

"Bootstrap is a toolkit from Twitter designed to kickstart development of webapps and sites. It includes base CSS and HTML for typography, forms, buttons, tables, grids, navigation, and more." Really nice – straightforward, elegant, and a good starting point for the scratchy websites I tend to end up making.

-

Fantastic.

-

Marvellous. Can't say any more – you need to read this (very) short story – but it's really, really lovely: shivers down the spine, and something heartwarming, all at once. And: set in a slightly magical part of the world.

-

"…the insight I had playing Indigo was that map-based games, while non-linear in gameplay, are inflexible in narrative. There’s nothing variable about the story that emerges in the player’s head: it’s authored, split up, and distributed across the game like pennies in a Christmas pudding. All that changes is the pace at which it appears. But in time-based games, everything the player does is story, and so that story is constant flux.

To put this another way:

Map-based games are ludicly non-linear but narratively inflexible.

Time-based games are ludicly linear but narratively flexible.

(Of course, these are spectrums: some games, like Rameses or Photopia are ludicly linear and narratively inflexible, and some, like Mass Effect, at least endeavour to be ludicly non-linear and narratively flexible.)

…

Do readers want to interact, toy and play with fiction, or alter, bend and shape it?" Jon Ingold is smart. -

Really ought to make some of this sometime; I'm a sucker for onion jam/marmalade, ad it's so easy, I have no idea why I haven't tried it before.

-

"Prototypes for Mac turns your flat mockup images into tappable and sharable prototypes that run on iPhone or iPod touch." Nice.

-

"My dream cloud interface is not about booting virtual machines and monitoring jobs, but about spending money so my job finishes quicker. The cloud should let me launch some code, and get it chugging along in the background. Then later, I would like to spend a certain amount of money, and let reverse auction magic decide how much more CPU & RAM that money buys. This should feel like bidding for AdWords on Google. So where I might use the Unix command “nice” to prioritize a job, I could call “expensiveNice” on a PID to get that job more CPU or RAM. Virtual machines are hip this week, but applications & jobs are still the more natural way to think about computing tasks." Yes, this. And: lots of people _think_ the cloud works like this, but it really doesn't, yet. Parallelization/adding computing power is more practical, but it's not been made easy like a bunch of other things have (so far).

Waving at the Machines

21 May 2011

There was a line in this blogpost about what it’s like to QA Kinect games that really caught my eye.

The cameras themselves are also fidgety little bastards. You need enough room for them to work, and if another person walks in front of it, the camera could stop tracking the player. We had to move to a large, specially-built office with lots of open space to accommodate for the cameras, and these days I find myself unconsciously walking behind rather than in front of people so as not to obstruct some invisible field of view.

(my emphasis).

It sounds strange when you first read it: behavioural change to accommodate the invisible gaze of the machines, just in case there’s an invisible depth-camera you’re obstructing. And at the same time: the literacy to understand that there when a screen is in front of a person, there might also be an optical relationship connecting the two – and to break it would be rude.

The Sensor-Vernacular isn’t, I don’t think, just about the aesthetic of the “robot-readable world“; it’s also about the behaviours it inspires and leads to.

How does a robot-readable world change human behaviour?

It makes us dance around people, in case they’re engaged in a relationship with a depth-camera, for starters.

Look at all the other gestures and outwards statements that the sensor-vernacular has already lead to: numberplates in daft (and illegal) faces to confuse speed cameras; the growing understanding of RFID in the way we touch in and out of Oyster readers – wallets wafted above, handbags delicately dropped onto the reader; the politely averted gaze whilst we “check in” to the bar we’re in.

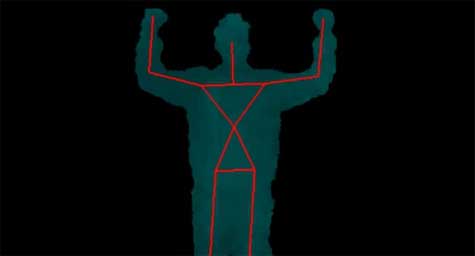

Where next for such behavioural shifts? How long before, rather than waving, or shaking hands, we greet each other with a calibration pose:

Which may sound absurd, but consider a business meeting of the future:

I go to your office to meet you. I enter the boardroom, great you with the T-shaped pose: as well as saying hello to you, I’m saying hello to the various depth-cameras on the ceiling that’ll track me in 3D space. That lets me control my Powerpoint 2014 presentation on your computer/projector with motion and gesture controls. It probably also lets one of your corporate psychologists watch my body language as we discuss deals, watching for nerves, tension. It might also take a 3D recording of me to play back to colleagues unable to make the meeting. Your calibration pose isn’t strictly necessary for the machine – you’ve probably identified yourself to it before I arrive – so it just serves as formal politeness for me.

Why shouldn’t we wave at the machines? Some of the machines we’ll be waving at won’t really be machines – that telepresence robot may be mechanical, but it represents a colleague, a friend, a lover overseas. Of course you’d wave at it, smile at it, pat it as you leave the room.

If the robot-read world becomes part of the vernacular, then it’s going to affect behaviours and norms, as well as more visual components of aesthetics. That single line in the Kinect QA tester’s blogpost made me realise: it’s already arriving.

The Game Design of Everyday Things

11 May 2011

I’m writing a new column for the online component of excellent games magazine Kill Screen.

It’s called The Game Design of Everyday Things, and is about the ways that the ways we interact with objects, spaces, and activities in the everyday world can inform the way we design games.

Which is, you know, a big topic, but one that pretty much encompasses lots of my interests and work to date. I think it’s going to cover some nice ideas in the coming weeks and months.

I’ve started by looking at that fundamental of electronic games: buttons.

Every morning, I push the STOP button on the handrail of a number 63 bus. It tells the driver I want to get off at the next stop.

I’m very fond of the button. It immediately radiates robustness: chunky yellow plastic on the red handrail. The command, STOP, is written in white capitals on red. There’s a depression to place my thumb into, with the raised pips of a Braille letter “S” to emphasize its intent for the partially sighted. When pushed, the button gives a quarter-inch of travel before stopping, with no trace of springiness; a dull mechanical ting rings out, and the driver pulls over at the next stop.

It’s immediately clear what to do with this button, and what the outcome of pushing it will be. It makes its usage and intent obvious.

This is a good button.

-

"More sea metaphors." This made me laugh a lot. (cartoon in Prospect).

-

"In his book of aphorisms, One Way Street, published in 1928, Walter Benjamin has a remarkable premonition. ‘The typewriter’ he says, ‘will alienate the hand of the man of letters from the pen only when the precision of typographic forms has directly entered the conception of his books. One might suppose that new systems with more variable typefaces would then be needed. They will replace the pliancy of the hand with the innervation of commanding fingers.’" I really like the notion of "commanding fingers", and understanding the movie from hands to fingers.

-

Went in sceptical, but this is a very good/solid presentation: the emphasis on going beyond chucking around the adjective "playful" and actually considering what makes (different kinds of) games work, and what they may/may not be applicable to, is spot-on. And a reminder that I'm behind on my reading, as usual.

-

"Hooray! Someone has put John Smith’s short film, The Girl Chewing Gum (1976), on YouTube… The film consists almost entirely of a single continuous shot of Stamford Road in Dalston Junction, a downbeat area of east London… The conceit of the film is that everything that moves or appears within shot – pedestrians, cars, pigeons, even clocks – is following the instructions of an omnipotent director who appears to be behind the camera: ‘Now I want the man with white hair and glasses to cross the road … come on, quickly, look this way … now walk off to the left.’ Pedestrians put cigarettes in their mouths, talk to each other, eat chips, take their glasses off, cast a glance behind them or look at the camera, all at the apparent behest of this offscreen director."