-

This isn't just 'good', 'nice read'; this is pretty vital. It all rings very true and reminds me of the best bits of the best places I worked. It's important for anywhere I work in future.

-

"Magic as Interface, Technology, and Tradition" – Greg and Dan's course sounds great.

Joe Chip’s problem was never his door

17 February 2015

The door refused to open. It said, “Five cents, please.”

He searched his pockets. No more coins; nothing. “I’ll pay you tomorrow,” he told the door. Again he tried the knob. Again it remained locked tight. “What I pay you,” he informed it, “is in the nature of a gratuity; I don’t have to pay you.”

“I think otherwise,” the door said. “Look in the purchase contract you signed when you bought this conapt.”

In his desk drawer he found the contract; since signing it he had found it necessary to refer to the document many times. Sure enough; payment to his door for opening and shutting constituted a mandatory fee. Not a tip.

“You discover I’m right,” the door said. It sounded smug.

From the drawer beside the sink Joe Chip got a stainless steel knife; with it he began systematically to unscrew the bolt assembly of his apt’s money-gulping door.

“I’ll sue you,” the door said as the first screw fell out.

Joe Chip said, “I’ve never been sued by a door. But I guess I can live through it.”

This passage from Philip K Dick’s Ubik has been doing the rounds recently, following a tweet from Ian Steadman:

Philip K Dick's "Ubik" (1969) manages to explain in half a page why the Internet of Things will suck under capitalism pic.twitter.com/PPnGEH5AzX

— Ian Steadman (@iansteadman) February 9, 2015

Steadman’s tweet has been enthusiastically retweeted and picked upon. See, for instance, Slate’s article Philip K. Dick Warned Us About the Internet of Things in 1969. That Slate article, like much of the attention Steadman’s tweet has garnered, misses the point spectacularly; it goes on to explain how terrible IoT is, and how prescient Dick is being.

The important words in Steadman’s tweet weren’t “Internet of Things”; the important word was capitalism.

Joe Chip clearly lives in a connected future. We know his homeopape machine talks to some kind of network, requesting news in a particular tone and fabricating it for him.

We know that the devices that make up his conapt know about his credit rating, and hence can refuse to work without either a line of credit or cash money.

The question really is: why does the apartment and its devices know about his credit rating? Why should it matter?

The clue is in the word contract. Joe Chip has signed a Terms of Service (TOS) agreement for his apartment.

Terms of Service, or End-User License Agreements, are problematic because they tend to exist for things you don’t really own: things like software, where even when you purchase it outright you agree to endless EULAs about what you can and can’t do with it; things that have a client-server relationship, where even if you own one end of it – the client – the server is still inside the domain of the corporation; things like subscription services, where the nature of the service (or the content within it, for a service such as Spotify) can change at any time.

It’s that Terms of Service that makes Joe Chip’s conapt suck. It doesn’t suck because it’s connected; it sucks because Joe Chip doesn’t own his own stuff. The TOS/EULA turns everything into hire purchase.

Subscription services make the expensive affordable (the very problem that hire purchase long ago set out to solve). A $600 iPhone is “free” on a particular contract… which often works out more expensive than the airtime and total cost of the phone. But ‘free’ is tempting, especially as the future becomes more expensive to partake of, and when cash upfront isn’t available. How many people have been stung when their ‘free’ device breaks inside a contract?

Joe Chip might have been, because, as we discovered earlier in the chapter (Chapter 3), he is broke:

“Mr. Chip, the Ferris & Brockman Retail Credit Auditing and Analysis Agency has published a special flier on you. Our reciept-slot received it yesterday and it remains fresh in our minds. Since July you’ve dropped from a triple G status creditwise to quadruple G. Our department – in fact this entire conapt building – is now programmed against an extension of services and/or credit to such pathetic anomalies as yourself, sir. Regarding you, everything must hereafter be handled on a basic-cash subfloor. In fact, you’ll probably be on a basic-cash subfloor for the rest of your life. In fact-”

He hung up.

Joe Chip has been able to afford things he technically couldn’t – his apartment, his lifestyle – by sacrificing something non-monetary for the privilege. He gives up particular freedoms in order to own things. Insert endless variants of “if you’re not paying you’re the product being sold” here, but note that Joe has made that an active choice: he is selling himself to own things.

What’s more insidious than the future Joe Chip lives in is a future where that isn’t a choice. IoT is so often dependent on that client-server model – which in and of itself isn’t an issue – but the ToS/EULA that comes along with it can be used to sneak all manner of other horrors onto the unsuspecting customer.

And what’s worse is when the static object, the object that intuitively feels self-contained, turns out not to be – hence the outrage about the Samsung TV that might be ‘listening’ to you. In this case, the sacrifice is that voice-recognition is easier outsourced CPU power and large, constantly updated databases somewhere on the Internet, rather than stored, statically inside a box – but how many people are really aware that a TV, even a Smart TV, is more often a two-way device than not?

The Amazon Echo is obviously not self-contained; it is a parasite that lives in your home, has a nebulous and confusing set of functionality, and which never fails to have me screaming what is the catch?

Objects that talk are useful, but objects that tattle aren’t. Joe Chip’s objects ought to make his life better, but that clearly stopped a long while ago. The horrors described in that chapter of Dick’s novel haven’t come to be because they objects are connected; it’s because of design choices the manufacturers have made to support those objects, and the financial strictures they, and Joe Chip, operate within.

That’s the nugget to really think about: Joe Chip’s house, and Samsung’s TV, are like that because somebody decided to make them that way. Maybe not somebody; maybe many somebodies; maybe somebodies operating within other processes.

In another tale of a strange lock, Bruno Latour writes that “things do not exist without being full of people, and the more modern and complicated they are, the more people swarm through them.” The Berlin Key, or how to do words with things, explores how social relations and societal forces are rendered in technology – and also, in the other direction, how technology is coerced by society. You can’t talk about the object divorced from the society and cultures it represents, but you also can’t discuss it without some attention to the technology of the object itself. And, bound up in that object, are people and culture and convention and politics.

The Berlin Key is a cracking essay. (It’s also a fascinating object).

Like the Berlin Key, Joe Chip’s lock also represents the society he exists in, encoding interactions, assumptions, and economics. An SF novelist like Dick can uses this as a shorthand for the world he wants us to see in a single thing.

But the Samsung TV – or the August Smart Lock – aren’t fictional inventions that serve as scene-setting and dramatic devices. They’re really things we can have – I hesitate to say ‘own’ – right now. And they are full of people, swarming through them, and those people bring the culture the exist in, along with the cultures they’d like to exist in in future.

And that means they’re full of a whole boatload of late capitalism. It’s important to acknowledge that explicitly, even if I’m not quite sure what to do about that.

I am pretty sure, though, that Joe Chip’s problem was never his door.

-

Via Denise. Useful reminders.

-

That looks like a good overview of flexbox to me.

-

Darius Kazemi on writing aphorism detection; if nothing, it's a lovely insight into how he thinks about problems, as well as some neat code examples.

Putting the nuclear option front-and-centre

15 January 2015

I was talking to Tom and some other people at Matt’s coffee morning this morning, and I mentioned a tiny piece of interaction design I was fond of (that was pertinent to our conversation). Tom said ‘write that up so I can point to it‘, so that’s what I’m doing.

A long while ago, at an agency job, I was sketching out wireframes and interactions for a web-based feed reader. It was designed for users who possibly weren’t that used to RSS, and so it needed to guide them a bit through the best practices of interactions.

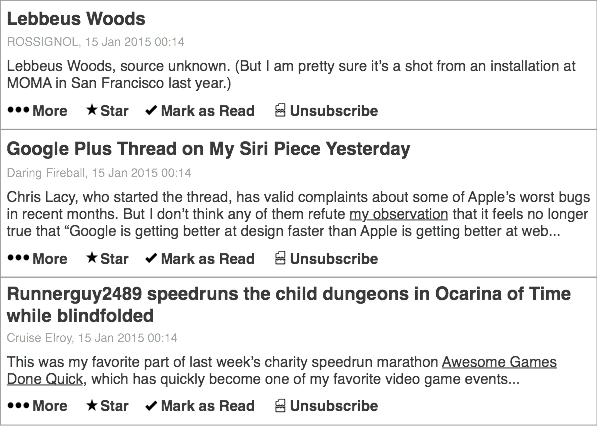

The list of articles looked a bit like this:

Pretty standard, although the important component was the unsubscribe button.

I put an unsubscribe button on every feed item.

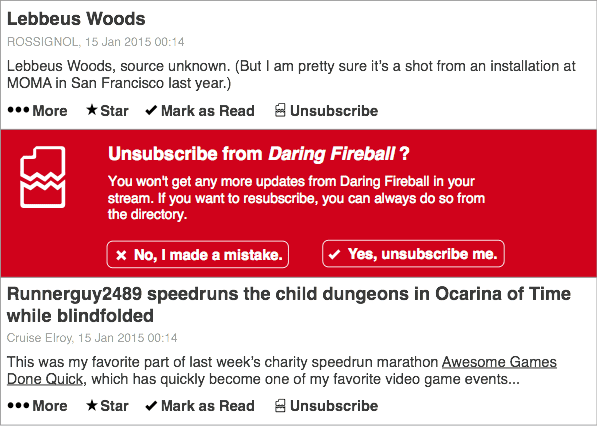

I wanted to stress that if you weren’t enjoying a feed, you didn’t have to read it. Just bin it! You’ll be a lot happier. Clicking the unsubscribe button would do something like this:

to indicate the severity of your action. I felt that was reasonable – little button, big confirm dialogue. And then boom: the entire feed is gone.

It’s amazing how often you can mark an item as read, or archive an email, before committing to unsubscribing. I wanted to capture how ephemeral subscriptions could be. They weren’t commitments; they were just things you’re interested in.

I think the me-of-2015 would also ensure that there was a way of triggering this interaction based on patterns of behaviour. For instance, asking the user if they want to unsubscribe from a feed if they’ve marked it as read a surprisingly short time after they looked at it (indicating they hadn’t read an entry). And, similarly, checking a few weeks later that you didn’t want to subscribe back: frequently, I unsubscribe from things just because I need a break, or I don’t have the space – not because I want them gone forever.

It’s very easy to offer final, decisive actions; they’re very native to dialogue boxes, buttons, and digital systems. But some things are ephemeral, and it’s important to stress that in design. Just because I unsubscribe form a feed, or unfollow someone on Twitter, doesn’t mean it’s final: I might want it back one day; I might be taking a break from my higher-traffic friends. I wanted to try encouraging that.

And I wanted to remind users that there was an alternative to ‘inbox overload’: you could just have a break.

In these two stills, drawn a bit from memory, there’s a lot of gaps – and I’ve not sketched any of the possible animation or motion that would help convey what was going on. Still, that interaction – offering what feels like the nuclear option front and centre, reminding the user that it isn’t a nuclear option – I quite like that.

-

This is a great talk by Zach Gage, from PRACTICE (I believe) on how to both design difficulty into games, but more importantly, how to help people become better at problem-solving, and the very specific relationship between shapes of problem, learning style, and difficulty. Great reading for game designers, but also recommended for any interaction designers, really.

-

Charming branding from Porto – just a lovely use of a system, but also one with wit and charm aplenty.

-

"When Smith describes the raids as “linear,” which allows the developers to “build on your knowledgebase,” he’s really describing something profound in the context of Destiny: the Vault of Glass is a game, where Destiny overall is merely a series of loops." Oh, that's a good way of putting it. (This is a strong article about one of the most interesting parts of Destiny – its first Raid. The Kirk Hamilton interview linked off it is excellent, too.)

-

Oh, awesome: a Pinboard Share extension for iOS 8.

-

New Danny Macaskill video: off-road (off ALL the roads) in Skye. Remarkable. Also: so much dronecam in biking videos now. (Nicely shot, thoguh).

-

Really, really useful: a tool from @mnot to test headers, caching, and responses to webpages. Will be using this a lot in future, am sure.

-

"The water that falls on you from nowhere when you lie is perfectly ordinary, but perfectly pure. True fact. I tested it myself when the water started falling a few weeks ago. Everyone on Earth did. Everyone with any sense of lab safety anyway. Never assume any liquid is just water. When you say “I always document my experiments as I go along,” enough water falls to test, but not so much that you have to mop up the lab. Which lie doesn’t matter. The liquid tests as distilled water every time." A truly lovely short story from John Chu.

-

The most useful tips in here: set the right headers; set the body of the response to an enumerator and it'll iterate over it, streaming it.

-

Some great Chess writing from Slate.

-

"‘If all that survives of our fatally flawed civilization is the humble paper clip, archaeologists from some galaxy far, far away may give us more credit than we deserve,’ the design critic Owen Edwards argues in his book Elegant Solutions." An excerpt from a Joe Moran essay on the paperclip.

-

"pup is a command line tool for processing HTML. It reads from stdin, prints to stdout, and allows the user to filter parts of the page using CSS selectors.

Inspired by jq, pup aims to be a fast and flexible way of exploring HTML from the terminal." That looks great.

-

"Something that journalists sometimes do is publish a disclosure statement. It’s sort of like an About Me page except it’s a listing of all their conflicts of interest—all the areas of coverage where you might have good reason to think they should not be trusted. It’ll say things like I once worked at Google or I’m married to an employee of Microsoft. I have never written one of these but I have fantasies about doing a comprehensive one. It would be the length of a novel, I think. An endless and yet incomplete litany of all the blood, privilege, history, and compromise on my hands." I could have quoted lots of this, but I chose this. It's good. It encapsulates the beginnings but not ends of lots of thoughts, and reminds me why, right now, I'm afraid of assuming anything about anything, why stereotyping "big companies" as being identical isn't just inaccurate but also unhelpful, and why the point of boundaries is that they always exclude _somebody_.

-

"Hatoful Boyfriend is the Fifa of pigeon romance and you should buy it for that reason alone." I'm loving the attention Hatoful Boyfriend is getting in the media; this review by Grant Howitt is charming, informative, and on the Guardian website. Brilliant.

-

Cracking interview with George Saunders, from 2011 (so pre-Tenth of December). Lots about the craft of writing, and about what Just Turning Up looks like. Also, his imaginary writing class in which Hemingway punches everybody out made me laugh out loud.

-

"Of course this is pure anthropomorphization. Bits don’t have wills. But they do have tendencies." This piece by Kevin Kelly is great – though this line neatly explains my suggestion that 'things' sometimes have 'desires' better than I ever have before.

-

Good to know SES can just be integrated as an ActionMailer delivery method.

The Shipping Forecast

16 September 2014

I worked there from 2009-2011 – employee #1, really. It’s a time and place I am hugely fond of. I learned a lot there.

I wrote something on a train last week after Matt’s post for week 483. I think it was mainly for myself; maybe I’ll publish it sometime. But then I found something better to share.

Warren Ellis’ The Shipping Forecast is a story in this year’s MIT Technology Review SF special, Twelve Tomorrows. On morning.computer, Warren explained his story thus:

When Bruce Sterling commissioned me to write a piece for MIT TECHNOLOGY REVIEW, he had a specific brief: imagine a future where BERG won, and launched the future from the back of their Brutalist gulag in Shoreditch. I dragged Schulze and Webb into the pub — Jones was gone by then, in his constant search for the next new thing, off to Google to direct larger launch facilities — and poured beer into them in an attempt to get them thinking about what was next.

I read the story last Friday morning; I had just got up to it in the collection. Over lunch, sat in the office canteen, I read the story. And this passage stopped me, entirely, in my tracks:

“We were very wonky back then. Everyone else was talking about drones and smart glasses and brain scanners and god knows what else, and we were trying to get washing machines to talk to the world. We got laughed at a lot. ‘Internet fridge’ was the punch line. We put the lamps and the early versions of the senders into people’s houses and people thought we were making toys. It took a while before people got what we were doing.”

“Well, you were inventing a business, right?” Emilija wasn’t sure where this was going and wanted to move it along.

“No,” said Signy, raising a finger. “Same mistake everyone else made. What we were doing was launching political probes into people’s homes.” She looked into her coffee cup and sighed.

“I’m not following,” Emilija said. “Political?”

“The personal is the political. Our social choices are political choices. We didn’t do the things that tech companies were supposed to do. We didn’t move fast and break things. We didn’t disrupt and abandon. We didn’t do moon shots. We created a future by sitting the world down with a cup of tea and a bun and asking it some questions.”

It’s just a story, about fictional companies and people, but reading it in week 483 winded me a bit; made me sit up sharply. And then breathe out, and remember to keep striving to achieve exactly that: a future that’s gentle, human, considered.

Thanks for the story, Warren. Thanks for everything, Berg.