-

Simon Katan on teaching peripheral skills around computing, computation, and code. I agree wholeheartedly with his description of tools that shield users from complexities to the extent of hiding how things actually work. I also loved his idea of "flour babies for looking after code properly".

-

Filed away as a nice introduction to computational sensing, vision, and how computers don't see.

Fun With Software

17 January 2020

The impetus for personal projects is, for me, often like coming up with a joke. You want to tell it as soon as possible, but you also want to tell it as well as possible. And you don’t want anybody else to do it before you, because nobody cares about you coming up with the same joke a bit later.

That means my thought process for making things is often a bit like this:

- Somebody should do X

- That sounds quite easy.

- If I don’t do it, somebody else will.

- If it’s easy, that will be quite soon.

- I should do X as soon as possible.

As time has gone on, my difficulty threshold has gone down: if it’s going to take more than an evening’s work, I’m not really sure I can be bothered. Especially if it requires hosting and maintenance. But sometimes, the perfect set of conditions arrive, and I need to make some nonsense.

This is how I ended up writing a somewhat silly SparkAR filter in an afternoon.

SparkAr is Facebook’s platform for making “augmented reality” effects for Instagram and Facebook camera. That translates into “realtime 2D/3D image manipulation”, rather than anything remarkable involving magic glasses. For the time being, anyhow.

Effects might work in 2D, through pixel processing or compositing, or by using 3D assets and technologies like head- and gesture-tracking to map that 3D into the scene. Some “effects” are like filters. They stylize and alter an image, much like the photo filters we know and love, and you might want to use them again and again.

Others are like jokes. They land strongly, once, and from that point on with diminishing returns. But the first point of landing is delightful.

In the popular Playstation game Metal Gear Solid from 1998, the hero, Solid Snake, sneaks around an Alaskan missile base, outgunned and outnumbered. In general, he will always do best by evading guards.

When a guard spots Snake, the guard’s attention is denoted by an instantly recognizable “alert” sound, and an exclamation mark hovering over his head. At this point, Snake must run away, or be hunted down.

The exclamation mark – and sound – have become a feature throughout the entire franchise, and gone on to be a bit of a meme.

That is all you need to know about Metal Gear Solid.

I wanted to to make a filter that recreated the effect of the alert, placing the exclamation mark above a user’s head, tracking the position of their head accurately, and – most importantly – playing that stupid sound.

In Spark this is, by most programming standards, trivial. Facebook supply many, many tutorials with the product (and, compared to the dark days of their API documentation nine or ten years ago, their new documentation standards are excellent).

I started with a template for making 3D hats, which matches a 3D object to a user’s head, and occludes any part of the the object falling ‘behind’ their head. Then I just had to lightly adjust it, replacing the hat with a flat plane that displayed a texture of the exclamation mark I’d done my best to recreate. That was half the work: putting the image in the right place.

What was more interesting was determining how the mark should pop-in, playing the iconic sound effect at the same time. The face-tracker offers lots of ways to extract the positions of facial geometry, and I spent a while tracking how far a mouth was open in order to trigger the effect. Eventually, though, I settled on the “raised eyebrows” outlet as being a much better vector for communicating surprise.

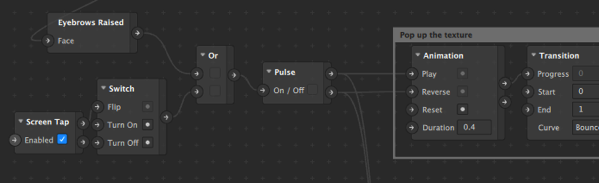

Some brief faffing in Spark’s node-based programming environment later, and now raising eyebrows triggered the brief animation of the exclamation mark popping in, and the corresponding sound effect.

Aside: I am not the biggest fan of graph/node-based coding, partly because I’m not a very spatial thinker, and partly because I’m already comfortable with the abstractions of text-based code. But this model really does make sense for code that’s functioning more like a long-running pipeline than a single imperative script. You find this idiom in game-engine scripting (notably in Unreal 4), visual effects tools, realtime graphics tools, and similar, and it is a good fit for these tools. Also: the kind of people coming to work in SparkAR will likely have experience of 3D or video tools. Increasingly, as I pointed out to a friend, “everything is VFX“, and so graph-based coding is in increasingly more places than it used to be.

I also made sure I supported tapping the screen to toggle the effect’s visibility. After all, not everyone has reliably detectable eyebrows, and sometimes, you’d like to use this imagery without having to look surprised all the time.

Finally, I added some muddy scanlines to capture the feel of 90s-era CRT rendering: a slight tint for that authentic Shadow Moses feel, coupled with rolling animation of the texture.

With this all working, I promptly submitted it for review, so I could share it with friends.

The output looks like this:

As with every single workflow where there is a definite, final submission – be it compilation, code review, or manufacture – this is exactly the point in time when I realise I wanted to make a bunch of changes.

Firstly, I felt the effect should include some textual instructions; if you haven’t been shown it by me, you might not know how it works. So I worked up adding them.

Secondly, I felt the scanlines should be optional. Whilst they’re fun, some visual jokes might be better off without them. So I wrote some Javascript to make a native option picker at the bottom of the effect, with the default being “scanlines on”.

Once version one had been approved, the point release was quickly accepted. And then I shared the filter in my story, and wondered if friends would borrow it.

(“Borrow”: the only way to share filters/effects it to use them yourself. Once they’re published, you have to use them in a story post of your own. Then, if a friend wants to “borrow” it, they can grab the filter/effect from your story featuring that effect. In short: the only way to distribute them is through enforced virality. I can even share them outside my protected account. I am fine with this; I think it’s rather smart).

When I first shared it with friends, one wrote back: “yay for fun with software“.

It’s a while since I’ve worked on a platform that’s wanted to be fun. I’ve made my own fun with software, making tools to make art or sounds, for instance. But in 2020, so much of the software I use wants me to not have fun.

I made my first bot on Twitter a long time ago, and from there, Twitter became my platform of choice for making software-based jokes.

Twitter is now very hard to make jokes on. The word ‘bot’ has come to stand for not ‘fun software toy’ but ‘bad actor from a foreign state’. The API is increasingly more restricted as a result. I’m required to regularly log in to prove an account is real. My accounts aren’t real: they’re toys, automatons, playing on the internet.

I get why these restrictions are in place. I don’t like bad actors spreading misinformation, lies, and propaganda. But I’m still allowed to be sad the the cost of that is making toys and art on the platform. (An art project I built for the artist Erica Scourti was finally turned off once API restrictions made it unviable).

Most software-managed platforms are not places you can play any more. I understand why, but I still wish that wasn’t the case.

Yes, I know Facebook, who are hardly a great example of a good actor, are getting me to popularise their platform and work on it for free. It’s a highly closed platform, and I’m sure they’ll monetise it when they work out how. I’m giving them free advertising just by writing this.

But. Largely, what I made is a stupid visual effect that neither they nor I can effectively monetise, and it’s a joke is better told than not told. In that case, let’s tell the joke.

I showed it to my friend Eliot:

Every single time I hear that sound and see it working, I laugh. Actually, sometimes I don’t: I’m busy holding a straight face with my eyebrows up, and somebody else is laughing. Either way, somebody laughs. And that’s good enough for me.

I know, intuitively, this is a not unproblematic development platform. I know it’s not really ‘free’ in the slightest. But I write this because, right now, it was a quiet delight to be allowed to make toys and play on somebody’s platform, and one of the more pleasant platforms they run (if you keep it small, private, and friendly). I’m sure they’ll mall-ify this like everything else, but for now, I’m going to enjoy the play it enables.

It’s a while since I’ve made a toy that was so immediate to build, so immediately fun for others.

Yay for fun with software.

(If you want to try the effect yourself, open this link on your phone. It’ll open Instagram and let you try the effect.)

-

On the problems of machine-learning and medical data.

-

"As serious intellectuals often do, we spent hours discussing these questions, what data we would want to collect to answer them, and even how we might go about collecting it. It sounded like a fun project, so I wrote a program that takes video captures of our Mario Kart 64 sessions and picks out when each race starts, which character is in each box on the screen, the rank of each player as the race progresses, and finally when the race finishes. Then I built a web client that lets us upload videos, record who played which character in each race, and browse the aggregated stats. The result is called Kartlytics, and now contains videos of over 230 races from over the last year and change." Yes, it's a plug for manta, but it's also a nifty piece of engineering.

-

"Termshows are purely text based. This makes them ideal for demoing instructions (as the user can copy-paste), making fail-safe "live-coding" sessions (plain text is very scalable), and sharing all your l33t terminal hacks." Really lovely: record terminal activity, upload it to a URL, share it with others, dead simple. And the client playback is all javascript. Lovely.

-

"Kittydar is short for kitty radar. Kittydar takes an image (canvas) and tells you the locations of all the cats in the image."

21st-century camouflage

29 June 2012

Max has finally written the brilliant article about real-time data visualisation, and especially football, that has always felt like it’s been in him. It’s in Domus, and it’s really, really good.

This leapt out at me, with a quick thought about nowness:

Playing with a totaalvoetbal sense of selforganisation and improvisation, the team’s so-called constant, rapid interchanges — with their midfielders often playing twice as many passes as the opposition’s over 90 minutes — has developed into a genre of its own: “tiki-taka”. Barça have proved notoriously difficult to beat, and analyse. Tactical intentions are disguised within the whirling patterns of play.

(emphasis mine)

It serves as a reminder of the special power to be gained from resisting analysis, of being unreadable. Resisting being quantified makes you unpredictable.

Or, rather, resisting being quantified makes you unpredictable to systems that make predictions based on facts. Not to a canny manager with as much a nose for talent as for a spreadsheet, maybe, but to a machine or prediction algorithm.

This is the camouflage of the 21st century: making ourselves invisible to computer senses.

I don’t say “making ourselves invisible to the machines”, because poetic as it is, I want to be very specific that this is about hiding from the senses machines use. And not to “robot eyes”, either, because the senses machines have aren’t necessarily sight or hearing. Indeed, computer vision is partly a function of optics, but it’s also a function of mathematics, of all manner of prediction, often of things like neural networks that are working out where things might be in a sequence of images. Most data-analysis and prediction doesn’t even rely on a thing we’d recognise as a “sense”, and yet it’s how your activities are identified in your bank account compared to those of a stranger who’s stolen your debit card. Isn’t that a sense?

The camouflage of the 21st century is to resist interpretation, to fail to make mechanical sense: through strange and complex plays and tactics, or clothes and makeup, or a particularly ugly t-shirt. And, as new forms of prediction – human, digital, and (most-likely) human-digital hybrids – emerge, we’ll no doubt continue to invent new forms of disguise.

-

"In this context, Google+ is not the company’s most strategic project. That distinction goes to Glass, to the self-driving cars, and to Google Maps, Street View, and Earth—Google’s model of the real, physical world. Maybe in twenty years we’ll think of Google primarily as a vision company—augmenting our vision, helping us share it—and, oh wow, did you realize they once, long ago, sold ads?" This is good. I like the distinction between pictures and vision a lot.

-

""And thus ends all that I doubt I shall ever be able to do with my own eyes in the keeping of my journal, I being not able to do it any longer, having done now so long as to undo my eyes almost every time that I take a pen in my hand; and, therefore, whatever comes of it, I must forbear: and, therefore, resolve, from this time forward, to have it kept by my people in long-hand, and must therefore be contented to set down no more than is fit for them and all the world to know; or, if there be any thing, which cannot be much, now my amours to Deb. are past, and my eyes hindering me in almost all other pleasures, I must endeavour to keep a margin in my book open, to add, here and there, a note in short-hand with my own hand." Well put. Well done, Sam. Well done, Phil.

-

"In making this list, Sterling privileges the visible objects of New Aesthetics over the invisible and algorithmic ones. New Aesthetics is not simply an aesthetic fetish of the texture of these images, but an inquiry into the objects that make them. It’s an attempt to imagine the inner lives of the native objects of the 21st century and to visualize how they imagine us." I'm never quite convinced by the Creators Project, and their introduction to this feels a bit woolly, but the interviews are all very good. This quotation, from Greg Borenstein, is excellent.

-

"It is a sign in a public space displaying dynamic code that is both here and now. Connected devices in this space are looking for this code, so the space can broker authentication and communication more efficiently." Gorgeous, thoughtful work as ever; I completely love the fact the phone app has no visualisation of the camera's input. Timo's point, about how the changing QR code seems to validate it more, seems spot-on, too.

-

"…let’s be clear that it is a phenomena to design for, and with. It’s something we will invent, within the frame of the cultural and technical pressures that force design to evolve.

That was the message I was trying to get across at Glug: we’re the ones making the robots, shaping their senses, and the objects and environments they relate to.

Hence we make a robot-readable world."

Solid Jonesgold. Very true, and something that's been in the back of my mind – like many others – for a while now.