-

Simple looking timing library

-

Oh god this is like catnip. I am going to pore over this in a bit. The gifs are fantastic.

-

1994 Tom Chick and I have a lot in common – a love of submarine sims and slightly over-technical flight simulators. And X-Com. (Well, UFO, really). A lovely piece of writing about what game design in 2012 looks like (amongst other things) compared to our youth.

-

Beautiful slit-scan photography.

-

Simple dynamic site generator with standardised templating tools: certainly looks nice for building those early-stage prototypes before you need a full backend.

-

"The history of switching power supplies turns out to be pretty interesting." It really does: long, fascinating post about a history of AC-DC conversion and how new technologies affected it.

-

"Remote terminal application that allows roaming, supports intermittent connectivity, and provides intelligent local echo and line editing of user keystrokes." As recommended by Matthew Somerville. Looks useful!

-

"Modern digital cameras capture gobs of parsable metadata about photos such as the camera's settings, the location of the photo, the date, and time, but they don't output any information about the content of the photo. The Descriptive Camera only outputs the metadata about the content." Lovely: a camera powered by Mechanical Turk.

-

"Seven hot air balloons, each with speakers attached, took off at dawn and flew across the capital. Each balloon plays a different element of a musical score, together creating an expansive audio landscape." Marvellous.

-

"It was supposed to be a £12,000 art project in which a helium-filled sculpture of a desert island floated eerily above the heads of spaced-out festival-goers. It has become instead a £12,000 art project in which a helium-filled sculpture of a desert island floats somewhere through the troposphere without anybody actually seeing it, or even knowing where it is." Awesome but sad all at once; and yet, expensive or not, it feels like a genuinely valid affordance of the art. Oh well.

-

"the footage gopro cameras produce is fantastic and i’ve seen some crazy stuff filmed with a gopro, but i think i found it’s achilles heel – my skateboard." The camera may be dead, but the footage is ace.

-

"Children will turn anything into a toy, any toy into a game and any game into a story. Adults do just the same thing, they just don’t do the noises. At least not when anyone’s looking." Yes. (Also: Sorrell is blogging. This is good.)

-

"Artist Rodrigo Derteano's autonomous robot plows the desert ground to uncover its underlying, lighter color, using a technique similar to the one of the Nazca lines, the gigantic and enigmatic geoglyphs traced between 400 and 650 AD in the desert in southern Peru. Guided by its sensors, the robot quietly traced the founding lines of a new city that looks like a collage of existing cities from Latin America." Oh gosh this is awesome.

-

And yet: this just explains how, and shirks any understanding of what the presentation of that information might signify, and instead, essentially, says "there was information, so I made an app, and everybody likes a league table, so I added league tables". It's data visualisation as technical endeavour, when, of course, it is far more than that; the moment you start presenting any information, you're making a statement about it, and nowhere does Gilfelt talk about what he feels the app signifies, or whether its editorial stance is appropriate, which makes me a bit sad.

-

"Holga D is a digital camera inspired from the extremely popular cult of Holga and other toy cameras of its kind. Even though it's a digital camera, it retains the qualities and simplicity of the original Holga camera and brings back the joy and delayed gratification associated with good old analog photography." I like this not because it's a digital version of a Holga, but what a digital camera might be like if it took the same approach as a Holga. I also really like the reversible top panel.

-

"Hybrids are smooth and neat. Interdisciplinary thinking is diplomatic; it thrives in a bucolic university setting. Chimeras, though? Man, chimeras are weird. They’re just a bunch of different things bolted together. They’re abrupt. They’re discontinuous. They’re impolitic. They’re not plausible; you look at a chimera and you go, “yeah right.” And I like that! Chimeras are on the very edge of the recombinatory possible. Actually — they’re over the edge."

-

Just in case you needed instructions.

-

Composite keys for Rails/ActiveRecord. Really does appear to work, too, which is nice.

-

"…the Duke Nukem Forever team worked for 12 years straight. As one patient fan pointed out, when development on Duke Nukem Forever started, most computers were still using Windows 95, Pixar had made only one movie — Toy Story — and Xbox did not yet exist." Fantastic, dense, Wired article on DNF from Clive Thompson

-

"For 16 days I lived with it strapped to me as I climbed through the valleys of central Nepal up to Annapurna Base Camp at 4,200 meters." Wonderful review of the GF1, framed as a travelogue, with real photographs. I'd be quite happy if all camera reviews looked like this.

-

"Copenhagen was much worse than just another bad deal, because it illustrated a profound shift in global geopolitics. This is fast becoming China's century, yet its leadership has displayed that multilateral environmental governance is not only not a priority, but is viewed as a hindrance to the new superpower's freedom of action." Mark Lynas on the reality of China's actions at Copenhagen. Worrying.

-

"Little stories are the internet’s native and ideal art form." Yes. This is a good one.

Lakitu as boundary object

11 April 2009

A little tidbit of a train of thought, found as I was going over my Skitch archives, and thrown out to the ether. I know exactly which train of thought I was using this to illustrate, and yet have no recollection of when I made it, or if I ever reused it.

In the interests of best practice, and Just Throwing Stuff Up: time to share!

-

"I’d recommend that if you’re considering or actively building Ajax/RIA applications, you should consider the Uncanny Valley of user interface design and recognize that when you build a “desktop in the web browser”-style application, you’re violating users’ unwritten expectations of how a web application should look and behave. This choice may have significant negative impact on learnability, pleasantness of use, and adoption." Yes.

-

Video from the side of a solidrocket booster from a shuttle launch – through launch, into the atmosphere, separation, and back down to splashdown. Incredible; hypnotic; magical to think that we made that.

-

"The first UK Maker Faire will take place in Newcastle 14-15 March 2009 as part of Newcastle ScienceFest – a 10 day festival celebrating creativity and innovation." Never been to Newcastle. That could be exciting.

-

"Don't be stuck staring at the screen! Mightier's unique puzzles are designed to be solved by hand with pencil and paper." You print out the puzzle, solve it with a pen, take a webcam picture of it… and the in-game laser carves the path you drew. Wow.

-

"It’s easy to roll your eyes at the people who look at an Xbox 360 controller or Dual Shock and say it’s too complicated. “Left 4 Dead” proves there are hardcore experiences — not just Wii and DS games — that can draw them in…but the controller remains a challenge that won’t be easily overcome." I'd never roll my eyes; modern pads are very complicated, and twin-stick move/shoot is one of the hardest skills to acquire. Still, a nice piece of commentary on what learning to use a controller looks like, and a healthy reminder.

-

"So when I play Fallout 3, and I think this is probably true for most people who are over forty, some part of me is always wondering if this is what it really would have been like. Not in terms of enemies, but in the way that humans banded together into small groups to create enough order to survive." Bill Harris on a perspective on Fallout 3 that I'll never have.

-

Click "CM Gallery". Watch. In order to illustrate the xiao's ability to not only take but also print photographs, Takara Tomy really pushed their anthropomorphic metaphor to the limits.

-

"Yes, it's true that at no time while playing Prince of Persia did I feel any of the frustration that I felt on a regular basis in Mirror's Edge. But neither did I ever feel the joy of doing something right, of stringing together a perfect series of vaults and wall-runs and feeling like it was based on my own skill. Can one exist without the other? Is it impossible to create joy without difficulty? I don't know. But Prince of Persia lost something significant." I'm a bit worried about the new Prince, especially having read this; the challenge/reward balance is hugely important to it as a series, especially since the marvellous Sands of Time. Also, more worryingly: are developers shying away from letting players fail any more?

-

"The Facebook Republican Army, based on Brighton's tough Whitehawk estate, looks for parties on Facebook. The gang boasts it travels nationwide – and has even bought its own coach." Oh boy.

-

"As the about page says, if you live exactly 6 minutes from Sunset Tunnel East Portal, 8 minutes from Duboce and Church, and 10 minutes from Church Station you may find it useful too." Bespoke tools for yourself that might happen to be useful to others. I like this a lot.

-

"The Firefox add-on "Pirates of the Amazon" inserts a "download 4 free" button on Amazon, which links to corresponding Piratebay BitTorrents. The add-on lowers the technical barrier to enable anyone to choose between "add to shopping cart" or "download 4 free". Are you a pirate?" Almost certainly not the first example; perhaps one of the best realised.

-

"That's how I got here. How long will it be before someone builds a raft and sets sail in space? Bill Gates has over fifty billion dollars. What if Richard Garriott had fifty billion dollars? If he wanted to, would that be enough money to build a rocket to get him into space, and a self-sustaining environment in which he could live? Would he want to sail away and never come back? … No matter what happened in our future, [whoever built that raft] would forever be the first. A thousand years from now, people would remember his name." Bill Harris is awesome.

Momentum

02 December 2008

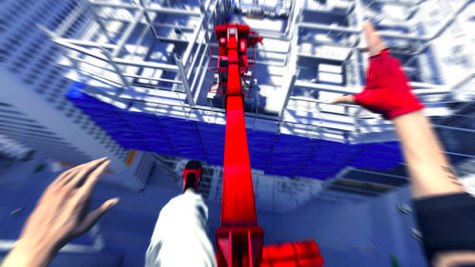

I’ve been trying to find a way into writing about Mirror’s Edge for about a month now, and during that time, the whole Reviewgate affair sprang up – in which Keith Stuart suggested that some of the reviews of Mirror’s Edge damning it with faint praise, and then suggesting that a sequel might solve some of its issues, might have got games criticism all wrong.

Trying to be critical around a game that kicked off another how-to-review-games (and what-are-games-anyway?) debate suddenly seemed even harder. But nagging at the back of my mind, was the need to write something. And then it made sense: the best way to approach the game was to come at it strictly from the angle of movement, and, more specifically, to examine its relationship to Parkour.

Mirror’s Edge is most notably for being a first-person game where shooting is pretty much optional and, a lot of the time, inadvisable. Instead, it places the act of motion itself front and centre: as Faith, a “runner” (the game’s parlance for traceur) you dart through the City as a free-running courier, free from the tight grips of a police state. Motion is the enemy of lockdown; running the alternative to putting up and shutting up.

I don’t really want to talk about technical aspects of the game very much, so it suffices to say that the engine and sensation of motion are remarkably well implemented; it realises the motion of not a camera at head height but a body superbly, not just showing you limbs at the camera’s extremities but genuinely making you feel like they belong to your character. It’s invigorating to play, and genuinely breathtaking to watch a skilled player navigate rooftops at speed. (If you’ve not seen the game, this is a good sampler).

But enough of that. What I really wanted to talk about was movement itself. Movement, and momentum.

As I played the game and went back (thanks to conversations with friends) to other writing on Parkour, the game’s first-person perspective made a lot more sense.

David Belle‘s comment on the physical aspect of Parkour is a good place to begin:

“the physical aspect of parkour is getting over all the obstacles in your path as you would in an emergency. You want to move in such a way, with any movement, as to help you gain the most ground on someone or something, whether escaping from it or chasing toward it.”

Whilst Parkour is, ultimately, an expressive form of movement, the aesthetic Belle suggests it strives for is one of minimalist elegance, rather than technical audacity. It’s not an activity for show-offs; the efficiency of movement takes priority over the way that movement looks.

Third-person games are great to show-off in. You can always see the player character on screen; it’s easy to understand how the motions the player undertakes with pad or stick translate into movement on the screen, and it’s easy to mentally connect the player to their avatar. Fighting games, notably, make for great spectator sports even for the unskilled spectator.

But by making Mirror’s Edge first-person, it takes the focus away from the aesthetics of motion and places them on the actual act itself – on the skill required. This makes it much less of a spectator sport – it’s always hard to engage with other people playing first-person games if you don’t know the game in question very well.

Mirror’s Edge forces you to approach the world as a runner or traceur, and take pleasure in the elegance and efficiency of your own movements, rather than the entertainment of others.

The game communicates it well through its tutorial. A fellow runner, Celeste, runs Faith through a few manoeuvres to get Faith back in shape after an accident. The advantage of this is that before the player performs each manoeuvre, they get to see it acted out by another character in the third person. Instead of being a form of showing off, this is a way of giving the player a mental model of what they look like in the world when they navigate it. After all, it’s initially quite confusing, relating the flailing hands and feet on screen to actions a character might undertake. Celeste’s demonstration helps to connect those dots. And in Faith and Celeste’s movements, we see another embodiment of Belle’s ideas around Parkour:

“The most important element is the harmony between you and the obstacle; the movement has to be elegant… If you manage to pass over the fence elegantly—that’s beautiful, rather than saying I jumped the lot. What’s the point in that?”

Belle knows that Parkour can’t just be purely functional, but it’s noticeable that elegant movement tends to lead to faster, smoother passages through the city. And that’s why it’s very noticeable that, despite the emphasis on maintaining momentum and speed throughout levels, Faith is never anything less than gracious in her movements. When her movements become ugly – taking heavy falls, slipping and missing a jump, pulling herself up onto a ledge – they tend to become slower, too.

Mirror’s Edge strives for a more internal understanding of what is beautiful and satisfying within it. Any notion of “showing-off” in the game is confined not to a third-person replay camera, to fetishise the movements of the runners, but to a time-attack mode, where players face off against one another. They are not comparing the aesthetics of the run, but their technique. To borrow a term from martial arts, Parkour is an internal art, and Mirror’s Edge captures that far better than I think many have commented on. It captures the subjectivity of the art not only in its first-person camera, but in its “Runner Vision”, that colours optimal paths through the level with subtle red tints. At times, though, it’s never clear if these are hints or actual objects – the iconic red cranes may well be red, and the coincidence of an environment that demands to be run through highlighting itself is a pleasing one.

It also captures a core idea of games: that movement itself can be fun, especially when moving inside the body of someone who is superior in ability or capacity than the player. Moving through Faith’s world is, at times, a massive amount of fun; it brings to mind a chain of motion through videogames, from charging through levels with B button jammed down as Mario to Sonic’s indestructible careering through Green Hill Zone. The ability to experience that in a much more realistic world is genuinely invigorating.

And momentum becomes a key concept within the game.

In a post I keep linking back to, Iroquois Pliskin explains that the key feature of Survival games is the conservation of limited resources. In Mirror’s Edge, that resource is not ammunition or open ground, but momentum; when you have it, your flight from the security forces is much easier than without it.

Which is why it’s such a shame that the game seeks to tear momentum from the player so often. Whilst the rooftops are reasonably straightforward to navigate with heat on your tail, the interiors are often confusing. Taken slowly, it would not take long to find optimal routes through them – but when you’re being chased by guards with submachineguns, who have the power to drain momentum from you with a single blow or shot, the stakes become much higher. And, of course, when you make those slow, clumsy maneouvres mentioned earlier, you feel as if you’ve failed. Faith should be nothing less than graceful in her movements, and for much of her flight, I made her barely perfunctory. I was letting her down.

And perhaps the worst momentum-killer is the game’s story. The plot itself is fine – the back of the game’s box is lucid in its brevity:

In a city where information is heavily monitored, where crime is just a memory, where most people sacrifice freedom for a comfortable life, some choose to live differently.

They communicate using messengers called Runners.

You are a Runner called Faith.

Murder has come to this perfect city and now you are being hunted.

That feels ideally suited to the fast-paced, no-nonsense world of the runner. In the game itself, however, this turns into a twin sister on the other side of the law, private security forces with too much power, and an awful lot of cutscenes.

The game’s story is at its best when expressed through the environment and motion. At one memorable point, you discover that the police are countering the Runners by training the officers to becomes Runners themselves. You stumble upon a training ground for police-runners; it’s a room built into what looks like an old silo, with a well-designed training course inside it. At the beginning of the game, it might have been a good tutorial, but now you can ace it. The wall has 05 daubed on it, indicating this is part of a more comprehensive training programme.

It’s a nice piece of environmental storytelling – and you have all of twenty seconds to take it in, because you are being chased by two police-runners. I’m not sure everyone will have picked up the subtlety in that room, and it’s a shame, because it’s a really important moment; instead, you focus on the cops on your tail, and run for the next red door at top speed. Similarly, whilst the flat-animated cutscenes provide a lot of exposition, they lack the emotional power of the two highly memorable in-game cutscenes (one about halfway through, and one right at the end) that demonstrate that DICE really do understand this whole first-person camera thing.

Mirror’s Edge is at its best in moments of free exploration, finding new paths over serene rooftops, feeling that sense of flow as you tuck your feet over a barbed-wire fence; when it captures the feeling of a body moving, be it through graceful falls or being violently hurled off a building by a former wrestler; feeling like you’re flying across the city.

It’s at its worst when, unlike on the rooftops and in the stormdrains, it places obstacles in its path – narrative, out-of-engine cutscenes, action-through-havoc that you can’t escape.

And especially when it makes you fail: Faith is clearly an experienced runner, and there are times where the player can’t live up to their avatar’s abilities. DICE choose to present that in binary success or failure, which has lead to criticisms of trial and error. Perhaps; at the same time, I’ve never encountered a single glitch or unrealistic motion throughout all my travels through the game. The coherence of the illusion is remarkable, and the price for that coherence is a definite kind of failure at times. I am not sure that’s necessarily a good enough excuse for some of the stop-start, but I feel that the coherence of the game’s illusion is something that isn’t praised enough. If only that could be provided without such a sensation of failing – not as a player, but failing the character you play.

It brings to mind Jump London. If there’s one thing Mirror’s Edge gets right, it’s the feel of the city under your feet. Faith doesn’t just exist as a character in a cutscene or as four disembodied limbs; she lies in the seams between her trainers and the concrete.

If anything’s emerging from all the coverage the game – and criticism of it – is getting, it’s that it is not for everybody, and perhaps that Marmite-y nature will prevent it having greater success. But whether or not it is good or bad, you need to understand that it is important. Other games have attempted similarly visceral first-person experiences, and they are few and far between: Trespasser was flawed, far more fatally than Mirror’s Edge; Breakdown wasn’t very good at all; and the excellent Chronicles of Riddick, made a very different use of first-person, primarily using it as a characterisation tool for a slower-moving but more powerful protagonist. Mirror’s Edge really is something new, and something different, and something that countless games and designers are going to learn from in the next few years.

And it’s for that reason you need to play it. It takes one of the earliest videogame-mechanics – moving from A to B past obstacles – and implements it not only in a 21st century manner, but places it at the heart of its philosophy. Not only that, it places it into a world that resonates vibrantly with that of the traceur: one of lines hidden through cities, playgrounds hidden in architecture, and resistance hidden in motion.