-

"My class handouts grew into a crude PDF textbook, which somehow escaped the walls of the school. Emails began to arrive asking me to conduct workshops. An editor at Routledge, invited me to elevate my drawings and prose to a publishable state, and the result was Handmade Electronic Music — The Art of Hardware Hacking" Might have to get this.

-

Ah, the joys – and pains – of finding what looks like a software bug… lies in hardware.

-

Won't lie: nearly had a little sniff at Marie's presentation during Playful 2013; a love letter to a town in Animal Crossing, and also to London. Safe travels, Marie!

-

This is a good explanation of how to get sharp Canvas-based rendering on iOS browsers. It was on Posterous, so the only way to get at it was this archive.org page. Sigh.

-

Ben on postboxes as boundary objects – with a nice map from Hello Lamp Post, indicating how the boxes were talked to, and suitable name-checks to The Crying of Lot 49.

Knitting

24 October 2013

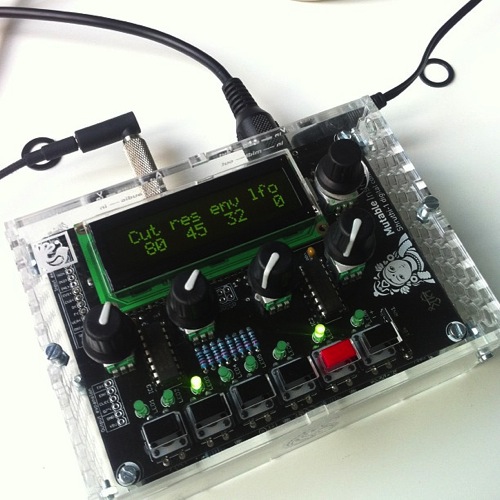

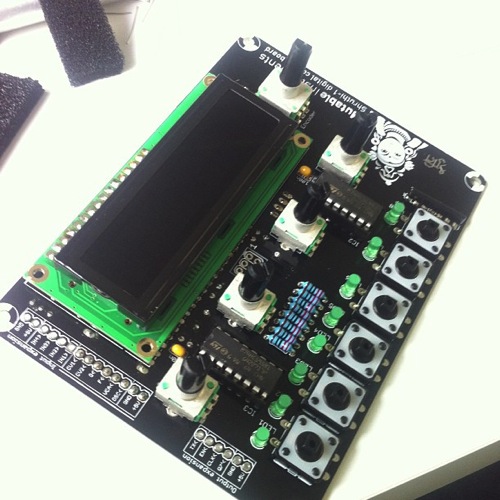

I built a synthesizer this year: a Mutable Instruments Shruthi. I didn’t design it or invent it; it was designed by Olivier Gillet, who released it in kit form. It’s not very expensive – about £150 with the case as well.

It arrived in a few plastic bags, and I also ordered the lasercut enclosure. And then, I spend a few happy afternoons putting it together.

All it required was moderately competent soldering, the ability to follow instructions, and patience. In that regard, it differed little from building Lego, much like I did when I was small. And for the seven or eight hours it took to build, I was lost in my work: entirely happy, paying care and attention to things being made with my hand – occasionally taking out the multimeter to check I hadn’t fluffed a joint.

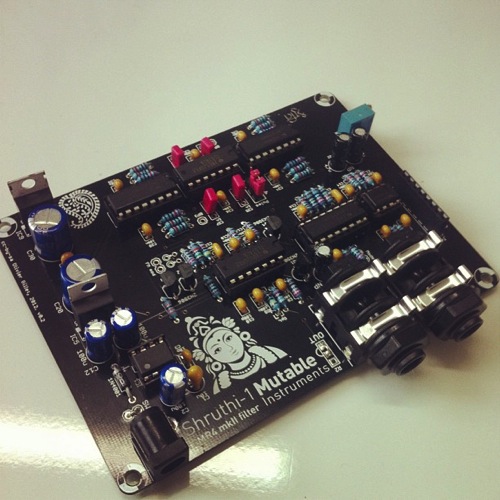

It’s a lovely instrument, with a really interesting sound. It’s a hybrid analog/digital synthesizer: digital oscillators and envelope, but analog filters. The filter is the bottom of the two PCBs, and there are lots of different ones available, for builders looking for different sounds.

Because of that weird structure, it’s not quite like your average analog monosynth. Yes, it can do that – but it also has all manner of interesting digital oscillators, not to mention wavetables (and custom wavetables if you want it), which you can step through with an LFO and… you get the picture. It has some really fat, interesting sounds; a bit like an ESQ-1. But there’s not much on the market like it – and nothing that sounds like it for less than about three to four times the cost.

It went together fairly smoothly, with only one error that came down to forgetting to completely solder in an IC socket. I mounted it in its case, and added two small switches – one for power, one to swap between two- and four-pole filters.

It’s hugely satisfying to make noises and music with something you’ve built with your own hands. And, though it’s just assembly, there’s a degree of craft going on; care and precision, using tools. That practice has definitely fed into the electronics I’ve constructed myself this year.

What I Talk About When I Talk About Knitting

I’ve characterised this sort of work recently as both whittling and knitting. Something to do with my hands, to empty my head, often between projects.

I think there’s value to just going through motions – what a martial artist would call a kata. It’s why I work through exercises on exercism even after I’ve hit a working solution; why I worked through the Ruby Koans even though I know the language. They’re both warm-ups and refreshers; it is good for the hands to go through motions before they start real work.

It reminds me of watching my Mum knit; she can knit during almost anything. She likes the things she makes, but I’m pretty sure there’s also just a habit of having something to do with one’s hands. It doesn’t always have to be challenging, or harder than last time. It has to be familiar, expected, calming. Progress, learning comes out of repeating the straightforward, just as much as it comes from trying new things. Craft is something to be honed as well as practiced.

A couple of months back, I left a theory-heavy conference session with an urge to make something, anything with my hands – just to offset a slight feeling of impotence that came out of lots of ideas being discussed without implementation. “Whittling for the soul,” I called it at the time.

The Shruthi sounds good, but it felt it’d shine with some effects – a shimmer of delay, or maybe some distortion.

It turns out guitar effects pedals are not that hard to build. This week, between some projects, I did some more knitting.

The Delay Box

There’s a huge culture, it turns out, of building your own effects boxes – the schematics of existing boxes are reverse-engineered and shared by guitarists on forums, and slowly they piece together PCBs or stripboard layouts. I got a bit lost in Tagboard Effects. But in the end I settled on this delay pedal, which happened to be available in kit form at Bitsbox (a favourite supplier of mine).

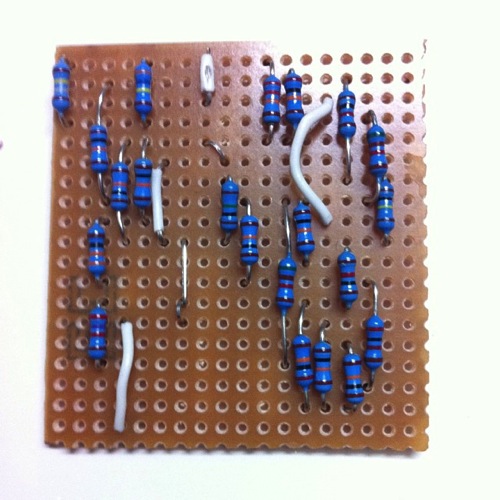

Again: I’m not an electronics engineer; I can piece things together, and have worked out a few little boards to package Arduino projects. This layout felt within my grasp – with hindsight, it was perhaps a bit ambitious for a first board.

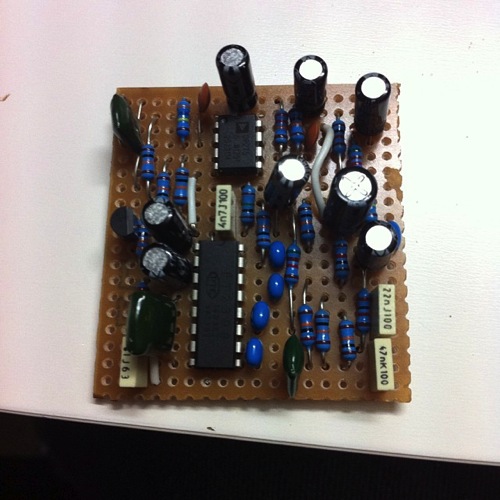

It took a handful of hours to put together the board, working through the layout, patiently cutting and linking the stripboard. I’m not that proud of the soldering on this, although coming back to it later, it’s not too bad.

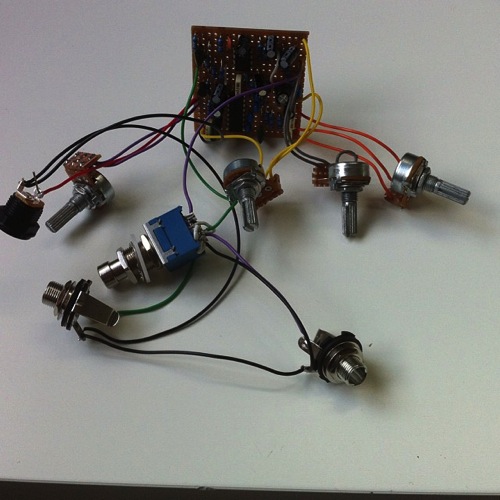

Once the board was populated, I started work on the offboard wiring: rigging potentiometers to little breakout boards, linking up the jack leads and DC socket. Next time, I’m going to do this once the components are in the box – I ended up with a correct circuit, but by god it’s a tangle.

Of course, a stompbox is nothing if it’s not in a box. So I sat down with a Hammond 1590B, a unibit, and a carefully laid-out template in Illustrator, and got drilling.

I’ve said it several times: boxes will chew you up and spit you out if you’re not careful. I did a reasonable job here – only one hole too large, and I could have been more generous with the spacing. Fitting everything inside was fiddly and tight – I was convinced everything was going to short out. That hole I cut too large led to internal space being cramped. And yet: somehow, I slotted it all in, screwed it tight, jammed the back on.

(It’s worth noting: Hammond enclosures, especially these pre-painted ones, have a great feel to them).

A few silver knobs, and the box was complete. The delay worked first time, and sounds delightful – not quite an analog tape delay, but not a perfect digital shimmer; just a hint of degradation as it tails off. Fiddling with the delay time whilst sound’s going through leads to lovely pitch-shifting, and it begins to oscillate and feedback really nicely in the right circumstances.

It didn’t work for a while – and then I discovered the box was fine; it was my jack lead that had sheared internally when I wasn’t looking. A new jack lead, and my guitar was shimmering and dancing away.

Yes, it was just assembly. But it was more than that, too. I refined my manual soldering skills again; I spent some time away from the screen, instead inhaling the delightful smell of solder fumes; I continued to level up at building enclosures – I think this was the most refined one yet, and my first in metal. A really nice artefact.

And again: the fiero of making sound, making music, with a thing you put together yourself.

It was a good piece of knitting in every sense.

I think this type of work is important. It’s easy to spend time learning new things, and pushing ourselves – but it’s equally good to spend time in a relaxing, comfortable space, and enjoy the act of executing well. Craft is not always about the new: it’s also about being able to repeatedly execute quality. Which is why making a simple thing well, is good for the soul.

And an added bonus: slowly, I’m heading back towards making types of music I’d not considered, on instruments and devices I’ve made myself. Next on the knitting list: a fuzz pedal or two, to be built when the next project is over. Or perhaps sooner, if my hands get itchy.

-

"…drawing, even at a representational level, is the construction of ideas. Therefore the conscious manipulation of ideas through the act of drawing becomes highly fruitful for a designer." More from Matt on drawing, and particular approaches aimed at unlocking drawing-as-thinking. Excellent as ever. I continue to vaguely try drawing in all workshops and for myself, and am still amazed by the number of people who, in design workshops, illustrate what they mean with sentences. For reference: I am a truly appalling draughtsman who was the despair of many an art teacher.

-

Both of these are great, and express some of what I've been trying to say in recent talks far better than I've expressed myself.

-

Rather good interview with MJH; covers lots of bases, carried out just before Light was published.

-

John Gray on M John Harrison – not just the Kefahuchi Tract trilogy, but also Viriconium and Climbers.

-

"…I feel like five or ten years ago we had a common critical vocabulary robust enough to talk about what is going on in low-agency, linear, or hypertext games, but that the community has shifted enough not to be using that vocabulary now that there are lots of such games to talk about." Emily Short's roundup of the 2013 IF Comp. Really good notes on the state of the modern competition; also good notes on the nature of interactivity. Worth your time.

Making Game “Feel”

22 October 2013

Game “feel” is hard to explain. It is, literally, something you have to feel for yourself: the tactility of a feedback loop that just works. And yet it’s not magic; it’s made, by a person, or by a team, and refined. There’s a good book on the topic. And no developer hits game feel right the first time, every time; it takes work.

I really liked this interview with Jan Willem Nijman from Vlambeer over on Rock Paper Shotgun. Graham Smith pins him down a bit and asks him to talk about why Nuclear Throne feels so good. Vlambeer always have great feel to their games – just think about Super Crate Box! – and it’s something they’ve become practiced at.

Nijman explains, and Smith presses him more and more for specifics. Which is great journalism, as Marsh Davies points out: if you want to talk about the “magical” responses of a technical system, why not interrogate those technicalities? Why not try to understand the medium in its own terms?

In the end, Nijman breaks down the various routines – primarily related to visuals and rendering – that happen when the player fires a single pistol bullet:

When you fire the pistol in Nuclear Throne, first of all the Pistol sound effect plays. Then a little shell is ejected at relatively low speed (2-4 pixels per frame, at 30fps and a 320×240 resolution) in the direction where you’re aiming + 100-150 degrees offset. The bullet flies out at 16 pixels per frame, with a 0-4 degree offset to either direction.

We then kick the camera back 6 pixels from where you are aiming, and “add 4 to the screenshake”. The screenshake degenerates quickly, the total being the amount of pixels the screen can shake up, down, left or right.

Weapon kick is then set to 2, which makes the gun sprite move back just a little bit after which it super quickly slides back into place. A really cool thing we do with that is when a shotgun reloads, (which is when the shell pops out) we add some reverse weapon kick. This makes it look as if the character is reloading manually.

The bullet is circular the first frame, after that it’s more of a bullet shape. This is a simple way to pretend we have muzzle flashes.

So now we have this projectile flying. It could either hit a wall, a prop or an enemy. The props are there to add some permanence to the battles. We’d rather have a loose bullet flying and hitting a cactus (to show you that there has been a battle there) than for it to hit a wall. Filling the levels with cacti might be weird though.

If the bullet hits something it creates a bullet hit effect and plays a nice impact sound.

Hitting an enemy also creates that hit effect, plays that enemies own specific impact sounds (which is a mix of a material – meat, plant, rock or metal – getting hit and that characters own hit sound), adds some motion to the enemy in the bullet’s direction (3 pixels per frame) and triggers their ‘get hit’ animation. The get hit animation always starts with a frame white, then two frames of the character looking hit with big eyes. The game also freezes for about 10-20 milliseconds whenever you hit something.

You just have to watch Nuclear Throne in action to see how meaty it is, how chunky it feels, and how clear the link between action and outcome is. The reason for that isn’t magic; it’s all the decision-making – both human and code – outlined above.

I’d argue that it’s neither science or art – it’s something more profound, that combines the two. It’s craft: the desire for a particular, sensual outcome as an artist; the technical capability to implement it; but above all, the craft of adjusting and readjusting, taking time, taking care, understanding that every possible detail is a thing under your control, and then just doing the work until it’s right.

-

"…we re-designed our lighting rigs in the computer to be very similar to traditional lighting rigs with bounces and blockers and things like that. The slight difference being we could make a white bounce card that was a kilometer by a kilometer if we wanted to bounce a light onto the ISS." Easily my favourite sentence from an excellent article on the effects work in Gravity – not just how they did it, but what their processes were like. I love this stuff, especially around the interaction between vfx and DOP.