-

"Here’s an important and (as far as I can yet tell) unaddressed question for Mare of Easttown criticism: when, exactly, did Mare Sheehan stop dying her hair blond?

This question may seem trivial compared to more pressing Mare of Easttown questions, such as “was that ending good?” and “is this copaganda?” However, don’t worry: all these are the same question."

Cracking writing about a cracking show, on the role of "femininity" in both the casting of drama and the plot of _Mare of Easttown_. The kind of essay that opens new doors without clsoing or criticising others.

The Thing That Gets You To The Thing

23 March 2020

I finished my rewatch of (all of) Halt and Catch Fire. I blame Robin for the push. And now, rather than just emailing my three friends who definitely care, I’m writing about it online.

Halt is one of my favourite TV shows. It took me a while to realise this, the first time around: I think I actually knew that for sure around season 3 (of 4). The final season is definitely my favourite final year of a show ever.

And here’s the thing, really, I just wanted to watch season 4 again. But season 4 doesn’t taste so good without the build-up to it. Really, I was signing up to go on a journey: I wanted to ride the rollercoaster again, and I wanted the end of season four to hurt in all the ways it does, to heal in all the ways it does. I wanted to rebuild my relationships with these characters precisely to feel a specific moment of grief in all the right ways.

(That moment landed, just as well as the first time, and everything else – the joy, the kindness, the friendship, the delight of watching reconciliation – landed too).

It’s a funny show. It starts out… quite badly, wanting to tell one particular story, and the moment it starts swerving away from that, it becomes more interesting. That point isn’t the beginning of season 2, incidentally: it’s easy to hate on the messy first season, but rewatching it, it confirmed that it course-corrects fast and hard. Once Donna is brought up in the mix around S1E4 it starts showing hints of what it’ll be, and the last few episodes of season 1 – pretty much once Donna says “I’m coming with you,” and the gang drives to COMDEX, are it taking flight. The rewatch definitely confirmed you cannot pull the “Parks And Rec Manouevre” (“just start with S2”) with this show.

But: it definitely improves, and it is one of the most impressive instances of a show seemingly deciding that it wasn’t working, changing everything up, and that actually working. What worked was, of course, the ensemble. What didn’t work was The Joe MacMillan Show. But Joe is a great character – maddening, obnoxious, and then at key times, not. So his role shifts up, and new characters get the spotlight in S2 – and that shift of focus keeps happening. Throughout the run, the structure of the show and the roles played by the same characters are constantly rejigged: who has power? Who wants it? Who is satisfied? Who is unfulfilled?

It’s easy to comment on how successfully the show reinvented itself. I think, though, that the way that also happens diegetically is perhaps my favourite thing about the show.

More plainly: Halt and Catch Fire is one of my favourite dramatic depictions of change.

Drama is largely about conflict and tension, and how that can be resolved: successfully for all, or with winners and losers. Characters change (or they don’t) in order to get what they want. But Halt does something more interesting: characters also change because life happens, and it changes them. It plays out over about 12 years, and one of my favourite things in the show is how the characters age, how they escape their old loops, how they become more themselves, and where they end up.

I get a little bit teary watching the Joe of the beginning of season 4: broken by so many things that have happened, smaller and subdued. But, quickly, it becomes clear that in some ways, he is happier and healthier. Watching him finally find ways to be happy but not at the expense of others; watching him work out how to be kind (and also watching others finally trust him, having understandably not trusted him for so long); watching his relationship with Haley, is a delight.

There’s a mirror to that in Cameron, too, who – once she escapes the lazy writing of the early episodes – takes off as a character. Cameron drives me absolutely spare for much of the show, and this is why I like the character; she is brilliant and frustrating, and the point of her character is that she cannot be one without the other. She drives me mad, and I love her nonetheless. I like seeing her win, feel for her many vulnerabilities, and hate seeing her hurt. She’s wrong (practically, but not ideologically), I think, about the inevitably terrible IPO, but I never forget Mackenzie Davies’ guttural scream when she’s voted down, and thus out of her own company. I never stopped hating that she had to feel that way.

The common thread for all the four leads is how terrible and unhealthy their relationships can be, and how much work it takes for them to even understand this, before they fix it. They think they can fix it through divorce, or estrangement, or destruction; what it takes is grief, and forgiveness, and acceptance, and time.

I rewatched because I wanted to watch the knot come undone, and then watch the characters tie it back together again. There is an unnameable pleasure in watching Joe work out how to be friends with Gordon, how deep his love for his business partner ultimately runs, after years of working together unhealthily. I love watching Cameron work out that she actually really likes Gordon as a pal when they don’t work together. I love that Cameron learns how to have the solitude and independence she knows she requires but also how not to push friends away. And I love that these are not things they earned through the twists of a few weeks that return them to where they began, but changed; I love that these are all-consuming changes, that take years to land. At the end of S4E10, it feels like so many of them are finally beginning.

And of course: it’s notable that their personal relationships reflect their work. Sat with me as I watched the end, my partner – who hasn’t really seen the show – asked if Comet was going to be another failure. And I said: “sort of, through no fault of its own. And Comet isn’t even the most successful company anybody runs during the series, or the best idea, really – but it is the healthiest, and that feels worth something“. Joe and Gordon make a place that really does work, for them, and everyone inside it, and they both learn that that perhaps beats being first, or best, or richest.

(Incidentally: I really like how the show manages to make its characters look ahead of their time and still fail. They exist in our world, but the reason you’ve never heard of them is they got beaten to the punch. All that drama in S1 trying to build a computer for the masses, a computer with personality, and getting it almost right, is neatly undercut by the moment Joe sees a pre-release Macintosh at COMDEX, and Lee Pace just sells a man seeing the thing he’s been talking about for so long made flesh, made better than he could ever have conceived, and made by somebody else.)

I’d never have put money on Halt being the show that made me feel these ways back in the dark days of a first watch of S1. Some shows are comfort-viewing because they’re about people who ultimately, feel like friends; they are nice to be with, they reassure you, any threat is short-lived. Halt is a deeper comfort, that is not always comfortable: the comfort of family. Family (the ones you have, the ones you choose, it doesn’t matter) are not always perfect, conflict is not always easily resolved, and people dear to you can still be entirely infuriating: but these feelings and conflicts are real because of how deeply they are felt. And that means that a comfort-watch about familial comfort is not always feel-good: by the end, I am watching not just to spend time with these characters I’ve come to love so deeply, but to support them; to hurt with them.

I wanted to feel all those things again, and I wanted to earn those feelings. The time-jump in NIM; the end of Who Needs A Guy; god, all of Goodwill; those moments land more because of everything invested. But most of all, like watching a plant grow, I wanted to watch people change, to be reminded that they can, and to see them learn to love themselves, because by the end, Halt and Catch Fire makes it clear exactly how hard that can be, and exactly how worth the effort to do so it is.

-

Interesting article on sync / music for TV and film from RA.

-

A spreadsheet cataloguing all of "wallflower"'s episode-by-episode guide to The Shield – his writing on it is so, so good.

Infinifriends

10 February 2014

Time to write up something that’s been sitting around on various disks for a while.

Many months ago, I saw Plotagon. It’s best explained as Xtranormal by way of The Sims: reasonable resolution, 3D-animated videos based on scripts; a desktop tool to generate them, and a site to host them.

Most interestingly, it’s scripted with what actually looks like movie scripts, and that got me thinking: what would it look like to feed it with procedurally generated scripts? Could you make the machine make videos? All I knew was two things:

- I know, for good or ill, how Markov chains work.

- All the scripts for Friends are transcribed on the internet.

After all, given Plotagon’s focus on semi-realistic forms, I decided that it was best suited to the great American artform of the 20th century: the sitcom.

The Infinite Friends Machine was born.

The machines does a few simple things. First, it scrapes Friends transcripts. For now, it works for most of Series 1. It then parses those scripts and chops them up into episodes, scenes, and lines attributed to individual characters. It also strips out some directions. Then, using all that, it offers ways to generate new scripts.

Markov Chains, as Leonard has frequently pointed out, are not always the best way of generating text alone, especially when the corpus you’re working from isn’t particularly consistent. He is, of course, right. Still, I enjoy the mental leap readers make in order to make generative prose actually make sense, and for this project, I mainly wanted to get to scripts as fast as I could.

Still, I didn’t want to hamper their relative crudeness, so I tried to skew things in their favour. To that end, the Infinite Friends Machine generates scripts by copying the structure of existing scripts. When it makes a new “episode”:

- it finds the scenes that are in the original episode it’s being copied from

- for each scene, it finds each line – who says a line at what point in the episode

- then, it generates a new line for the speaking character from their own corpus. That is: Joey only ever things derived from Everything Joey Has Ever Said. What this means is that the main cast have quite diverse things they might say, and the bit players pretty much only say the same thing. Gunther is quite boring.

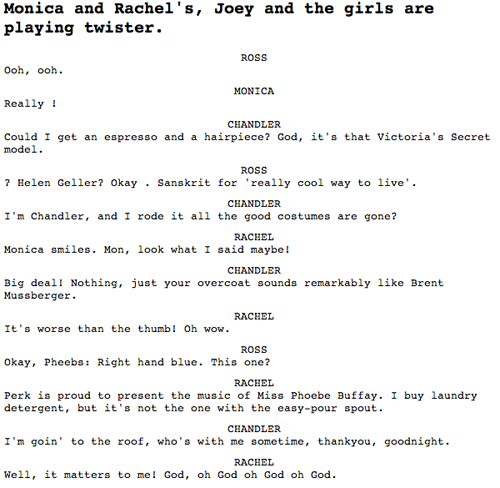

That’s it. A few seconds later, it spits out a nonsensical episodes of friends. Here’s a scene:

The machine isn’t online because it’s quite crude and processor-intensive, but you can get at the sourcecode from Github.

Anyhow: machine to generate scripts. Next stage: get them into Plotagon.

This was where my troubles began. For starters, despite having a nice format for scripts, Plotagon really demands you enter them via its UI – you can’t paste a big block of text in, you have to enter it by hand. Painful.

Next: Plotagon only lets scenes have two characters in. I decided to make a single scene – the tag on the end of the episode. But this turned into many scenes in Plotagon, as four people in an apartment was a bit much for it. I had to keep track of who was where, who was talking to whom at any point.

And then I had to deal with the unfortunate truth: Plotagon is horrible. I mean, Xtranormal used its non-realistic avatars and computer-voices to comic extent. By contrast, here we had disappointing voice acting with clunky visuals. Also, I had to add some ‘acting’. This largely consisted of making Chandler say everything whilst doing the (crazy) emote, to really capture that Series 1 Matthew Perry vibe.

A quick sting later, and Infinifriends S1E1 existed:

It is not exactly high art.

Just one scene took long enough, and I think, proved my point to an extent, but probably can’t be improved on for now. I’m not sure if I’ll ever return to the Infinite Friends Machine, but it was an entertaining enough exercise, and the video rendition is probably worth it for the cringe factor alone.

Theme tune. Credits. Tune in next time.

-

"The least important question you can ask about Engelbart is, "What did he build?" By asking that question, you put yourself in a position to admire him, to stand in awe of his achievements, to worship him as a hero. But worship isn't useful to anyone. Not you, not him.

The most important question you can ask about Engelbart is, "What world was he trying to create?" By asking that question, you put yourself in a position to create that world yourself."

-

"It has some unique perspective every once in awhile, but honestly, America can be super derivative. Most of the stories have already been on The Simpsons."

-

Oh, Brian. Funny and kind-of-right in equal measure.

-

"This TV is playing a built-in MPEG of static, instead of just displaying solid blue or solid black like they used to do. I think that's kind of awesome. The map has become the territory." Blimey.

-

"When I started writing this post, I didn’t have a conclusion in mind, but now that I’ve got to the end, the thing I want us to remember next time is just that: all the scales matter. Every part is important. The two days Sarah and Brian spent moving small pieces of vinyl, Ivan’s 4am printing-and-cutting, FOUND’s jumping-up-and-down to see if crowd movement broke their tech, last-minute shopping trips for slightly larger balls, all the things. Worry about it all. Fix everything." Lovely write-up from Holly of the big thing we did in Edinburgh. Also: good about the nature of the huge, and good about the nature of work. Worry about it all. Fix everything.

-

"This is a cross between Minesweeper and an RPG. You gain levels by killing weak monsters and win when you defeat them all. It's a bit different than Minesweeper in that the number you reveal when you click on a square is the total of the levels of the monsters in adjacent squares." Uh-oh.

-

"His earliest revelation about how the TV medium worked—one that heavily influences Community—came courtesy of a Cheers board game he spotted at a toy store. He realized that the characters were so relatable and their dynamics so clearly defined that anyone could step into their lives—even in a board game." Brilliant interview with Dan Harmon – but this paragraph really leapt out at me.

-

An unexpected place for a Le Guin interview, but it's great nontheless.

A quick guide to Inspector Spacetime

30 September 2011

So: a new season of Dan Harmon’s marvellous Community has begun in the US. It’s a very, very funny sitcom. It’s also a very funny sitcom that frequently plays on the expectation that the audience is deeply versed in pop culture, with entire episodes that pastiche movies and genres. You should watch it.

In S03E01, which aired last week, Abed – the TV geek inside the show – is distraught that his favourite show (Cougar Town) has been moved to mid-season – “never a good sign“. Afraid it’ll be cancelled, his friends try to find him a new favourite show. And, eventually, they stumble upon “a British sci-fi show that’s been on the air since 1962“:

Inspector Spacetime.

This is already a fairly brilliant joke – the phone box! The reboot-pastiching title card! And, you know, I hope it’ll return to haunt the rest of series.

But: then, the internet worked its magic.

The thing that has been entertaining me beyond all measure this week is Inspector Spacetime Confessions.

This is a tumblr account of a popular format: the “Confessions” format, in which fans of TV shows, books, movies, etc, post “secret” confessions about their take on characters, episodes, or arcs (sometimes, secret crushes) as text written across images. Amateur photoshop at its best. It was huge on Livejournal, and it’s ideally suited to Tumblr.

Except: there are, currently, about fifteen seconds of Inspector Spacetime in existence.

This, of course, does not matter when you’re TV literate. What’s happened is: fans are just making it up. They’re back extrapolating an entire chronology based on fifteen seconds of “tone”, and their entire knowledge of the Doctor Who canon.

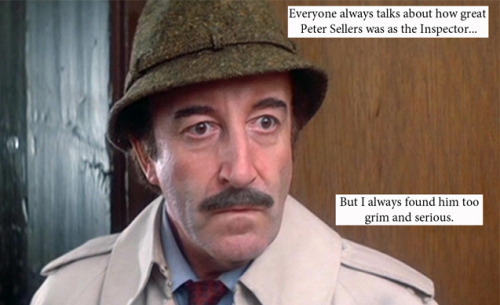

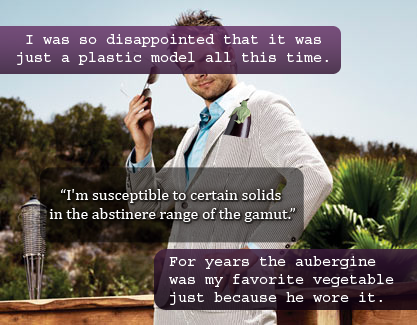

So, they’re diving into gags about former Inspectors:

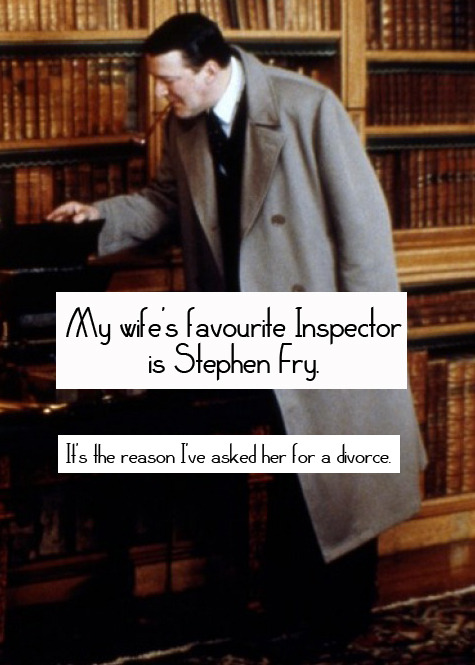

They’re torn about Stephen Fry:

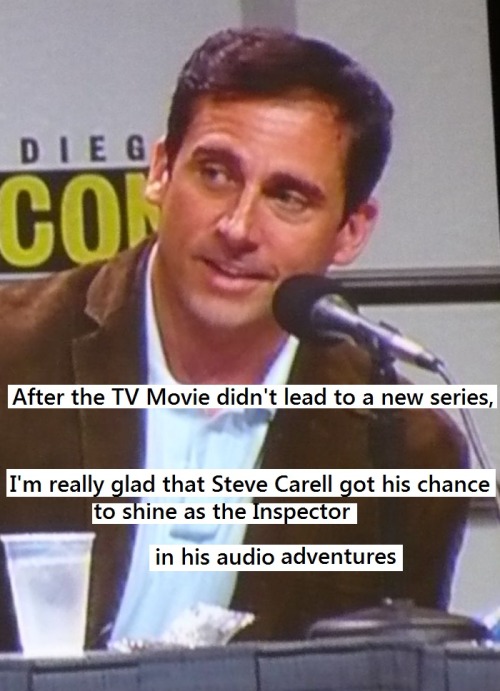

The Steve Carrell TV movie wasn’t well received:

And of course, they’re concerned about pocket fruit:

But there are more sophisticated jokes emerging. Like this one:

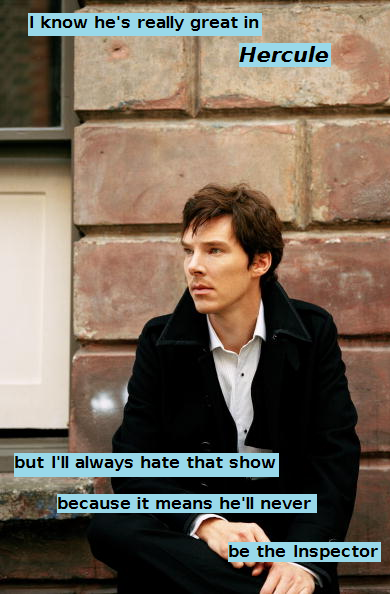

This presumes, in the form of a “fan confession”, that: the showrunner of Inspector Spacetime is also running another show – Hercule – which appears to be a modern-day Poirot reboot, and of course, because Benedict Cumberbatch is starring in Hercule, he’ll never be the Inspector.

This is sophisticated on a bunch of levels, but its elegance is in the way that entire gag is contained in one sentence and a photograph.

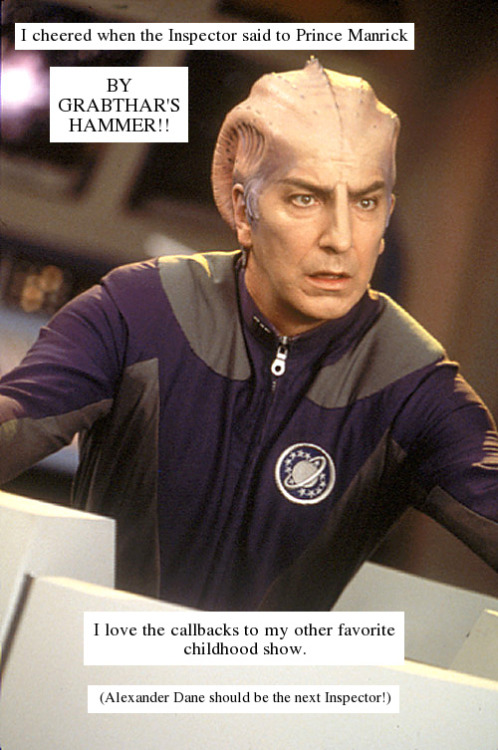

Or how about this:

which presumes Inspector Spacetime lives in that land of fictional TV shows, and thus a fictional actor (Alexander Dane) who starred in Galaxy Quest really ought, one day, to return to SF as the Inspector.

There’s a slowly emerging canon, thanks in part to the Inspector Spacetime forum. A lot of the canon is useful – the DARSIT feels better than the CHRONO box, everyone’s sold on Fee-Line – but it’s sometimes nice to see people buck it, or introduce new ideas (and Inspectors) in the most throwaway of Confessions. All this, from a fifteen-second joke that we don’t know will continue (or if it’ll introduce continuity we don’t know about yet).

And yes, Dan Harmon knows about it.

In the week between the two most recent episodes of Community, this has given me a vast amount of joy; I’ve been rattling the various configurations of Inspectors and Associates in my head, trying to remember my favourite episodes of a sci-fi show that never existed. And then giggling at the ingenuity and brilliance of some of the other confessions appearing – of the whole fictional history they bring to life, of Liam Neeson’s run in the 80s or the creepiness of the Laughing Buddas.

It’s really hard to explain the joy (especially as someone fascinated by the inner workings of serial drama) that this brings me. It’s a funny kind of magic – it’s unofficial, didn’t happen on TV, and just relies of fans’ understandings of not only TV shows, but how telly itself works. The results are just brilliant.

I’m off to write my own confession now. There’s always room for one more.