-

"Good art is a kind of magic. It does magical things for both artist and audience. We can have long polysyllabic arguments about how to describe the way this magic works, but the plain fact is that good art is magical and precious and cool. It’s hard to try and make good art, and it seems to me wholly reasonable that good artists should be concerned with their work’s cultural reception." Oh, this.

-

Looks like I'm going to have to go get me an Ordning Timer soon, to go with the intervalometer.

-

"I’m aware on some level that a photograph is misleading but at the same time we have to remember that photographs are just a frame in time. By its very nature the medium is misleading. We don’t know what is happening outside the frame, we don’t know what happened before the frame, we don’t know what happened after the frame. So I carry in my head two feelings about the Falling Man. On the one hand he was no different than the other jumpers on the day but at the same time I hold onto the essential truth that the image represents." Sontag's "moment selected at the exclusion of other moments" again.

Mousehole

11 September 2011

Mousehole Timelapse from Tom Armitage on Vimeo.

Been away from a week, in a little cottage with a view of this harbour. Turns out my homebrew intervalometer works pretty well – although it’s going to need more robust packaging in future.

Nikon D-Series Intervalometer

17 May 2011

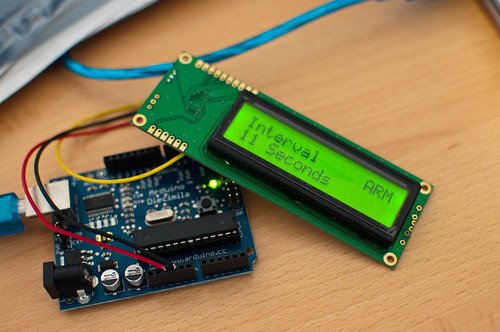

So, here’s a thing I’m making.

My Nikon D90 can be triggered by the cheap ML-L3 IR remote. It costs about £15. You point it at the camera, push the button, and it takes a picture.

This remote works with everything from the D90 down (so, towards the D3100/D40 end of the line).

What these cameras don’t have built in, however, is an intervalometer: a timer that will make the camera take a picture every n seconds or minutes. (The D300 and up (and, I believe, the new D7000) have a built-in intervalometer.)

I thought it might be interesting to build one. The project had a few criteria:

- It couldn’t be hard-wired to a computer. It had to be a stand-alone, battery-powered device

- It had to have a half-decent way of controlling it; ideally, not just stabbing at buttons.

- I wanted it to have a 16×2 LCD screen, mainly because I wanted to both design for that constraint, and work out how to control said screen

- Ideally, it wouldn’t require taking apart an ML-L3 remote to build.

Here’s where we are:

End-to-end: it works. Note that I said “making” earlier, though: it’s still not finished, because it’s not packaged. And whilst packaging is difficult, I think that’s what’ll make it feel finished for me: a black box I can easily take into the field.

You turn it on, rotate an encoder to set a time, and click the encoder in to arm it. Hold the encoder to disarm. The time varies from 1 second to 15 minutes – after 90 seconds, it increases in minute chunks. (15 minutes is the maximum time the D90 will stay on before powering down).

Most people ask me why it says “SAFE” and “ARM”. Well, it sounds a bit threatening, but I genuinely believed that OFF and ON were inaccurate, in that the device is “on” if the screen’s on. So I was just referring to the state of the timer. And something that fitted into four characters would work well with the layout of the screen I’d chosen.

How it works

There’s very little componentry here, but each section of the Intervalometer was a neat little thing to learn on its own.

First, the IR trigger itself. Nikon’s IR remote is relatively simple: a button, some circuitry, and an IR LED. Pushing the button doesn’t just light up the IR LED; it fires a very short “coded” burst of light, so that the only thing it’ll trigger will be a Nikon camera.

Fortunately for our needs, there’s an Arduino library called NikonIRControl, which emulates that coded burst in software – so a single command will send the appropriate burst to a digital output pin. That’s our IR trigger sorted, and all we’ve had to buy is an IR led. Which feels better – and cheaper – than just soldering two wires to a Nikon remote.

The screen is a 16×2 LCD, with a serial “backpack” pre-attached. That means I can just send serial data to it over a single wire, which again, keeps the number of wires from the Arduino down. I’m using the NewSoftSerial library to talk to it, which makes life easy.

The main controller is a quadrature rotary encoder with a push-switch in it. The switch is easily read, like any momentary push-switch on an Arduino. The encoder is a little trickier, because it’s encoded. In the end, I read it off an interrupt, using code from this page – and then smoothed it out a bit by making it only read every other click.

Finally, there’s just the case of the timer. Timers are a bit more fiddly than I’d have liked. You can’t just use delay, because that delays all code on the chip. I tried doing various things including counting milliseconds, but in the end, relied on the TimedAction library, which works well enough, and does a similar thing without my broken code.

Once each piece was in place and working, it was just a case of pulling it all together. The code – which is available on Github – is broken down into a series of files, pretty much one for each section of the project. I found this much easier to manage than the tyranny of One Big File.

For piecing the hardware together, I built a simple “shield” out of a piece of Veroboard. I got a lot of laughs when I said I was using veroboard, but it worked very well for me. With some headers soldered in, it was quite easy to line it up with the Arduino – making it easily changed, but also swappable. The usual electronics-debugging issues aside, this went fairly smoothly, and it only took a battery pack to give me a portable – if fragile – working intervalometer.

What’s next? Obviously, packaging it up – something sturdy and black, with an obvious power switch and that big knob. I was considering moving it to an Arduino Mini, for size reasons, but am not sure I can face more electronics debugging. Similarly, I’m not sure I’ll build a dedicated PCB or anything like that, yet.

But: if I can get this lot into a box, that’ll be good. Also: I should take some timelapses with it.

So whilst it’s not what I would call “finished”, it is an end-to-end demo – and that feels like good enough to share with the world.

(And, of course: if you’d like to use – or build on – my code, you’re more than welcome to.)

-

"Jennifer Brook, who makes artists’ books and iPad apps, speaking earlier this year: “Craftspeople are technologists, and technologists are craftspeople; the only difference is the velocity of the material they choose to work.” Humbly, I would add a further qualification, a further dimension. Celerity, or “proper velocity”, is velocity which takes the effects of relativity into account: the observer is travelling too; we are all travelling in time. The material has its own celerity." Oh, gosh, that's marvellous. Both parts.

-

Nice lo-fi sound effect tool.

-

Totally marvellous: photographs of New Zealand arcades in the eighties. Lovely they're online, as well as in the world, and must get around to that essay at some point.

-

"I’ve been doing some experiments using Processing to generate different patterns and sequences, a projector, and a camera pointing to the projection screen. Some of them are using a technique called procedural light painting, some other combining slit-scan with projected patterns. I’m also very interested in the low repeatability of some of these experiments, like the picture above, due to the noise introduced by the asynchrony of generation, communication and output means. Maybe we can call it Generative Photography." Really nice; interesting overlaps with some of the stuff from Shadow Catchers (in terms of structuring the capture, rather than the release, of light).

-

"It was May 1991. She was 89 years old. She often spoke of herself in the third person. She had a strapping male secretary named Horst." Jordan Mechner interviewed Leni Riefenstahl. Blimey.

-

Library to send appropriate pulses to an IR LED to trigger Nikon cameras

-

"TimedAction is a library for the Arduino. It is created to help hide the mechanics of how to implement Protothreading and general millis() timing. It is sutied for those actions that needs to happen approximately every x milliseconds." Aha.

-

"This library is a collection of routines for configuring the 16 bit hardware timer called Timer1 on the ATmega168/328." (Timers look hard).

-

"I know we've covered this to death already, but just a brief moment of silence, please—today, December 30th, is the last day that Kodachrome film will be processed anywhere in the world, ending a remarkable run that began in 1935."

-

Ben Benvie hiked all 2000miles+ of the Appalachian Trail, and took his camera. These are his pictures from Maine, the final state of the trail, and it just looks brilliant. I am not sure I could do this, but the appeal is enormous.

-

Images captured via Google Streetview cameras; some are incredible, others, beautiful.

-

"It’s different things at different times, a serious research tool, or a communication device, but it’s a toy, I can play with it and find things I didn’t know existed." Tom Phillips has made a version of A Humument for the iPad, and I am very excited about this new.