-

"Die Hard asks naive but powerful questions: If you have to get from A to B—that is, from the 31st floor to the lobby, or from the 26th floor to the roof—why not blast, carve, shoot, lockpick, and climb your way there, hitchhiking rides atop elevator cars and meandering through the labyrinthine, previously unexposed back-corridors of the built environment?" Marvellous, marvellous article, citing that Weizman piece I always end up citing, and looking how John McClane traverses the Nakatomi Plaza tower not through its corridors and elevators, but by literally infesting it.

-

"As computer technology has evolved to make artificial images look ever more real – so that the latest generation of shooter and war games will look as realistic as possible – ajpeg is intended to go the opposite way: Instead of creating an image artificially with the intent of making it look as photo-realistic as possible, it takes an image captured from life and transforms it into something that looks real and not real at the same time." Beautiful.

-

"Grit: The skills for success and how they are grown, a new Young Foundation book published on Tuesday 30 June argues that Britain's schools need to prioritise grit and self-discipline. Drawing on evidence from around the world it shows that these contribute as much to success at work and in life as IQ and academic qualifications."

-

"What’s happening here is a very neat trick. While Link can move a single pixel at a time, in any direction, the longer he continously moves in any direction the more he gravitates toward aligning himself with the underlying grid of the screen." Lovely little analysis of the different ways the original Legend of Zelda, and the subsequent Link to the Past, subtly correct the player's input to ensure they never feel cheated by pixel-perfect hit detection.

-

"A dude by the name of Phoebus has posted a collection of his research on Left 4 Dead's infected and weapon damage statistics over on the official Steam forums. I think that it'll be of great interest for any serious player of the game to delve into this information." There's a question over their accuracy, but there's still a decent amount of detail here, and the details on tail-off of weapon damage is useful to know. Also a relief to have the hellacious friendly-fire damage on Expert confirmed.

-

Fascinating to watch some of the body shapes – the hunched run, and in particular the the saut du chat – carry through to modern Parkour; that which is practical has always been so. As with all parkour: parts of it are beautiful, parts of it entertaining, and parts of it superhuman.

-

"Bourne wraps cities, autobahns, ferries and train terminuses around him as the ultimate body-armour, in ways that Old Etonians could never even dream of." More on this topic from Jones; still think there's something we're not quite hitting yet, but it's all good stuff.

-

Stack lets you subscribe to a selection of independent magazines; you choose how many you want a year, and they send you a selection. A really nice idea, although it'll be interesting to see them broaden their horizons a bit.

-

"Program recipes should not only generate valid output, but be easy to prepare and delicious." Chef is a programming language where the programs are also valid (if strange) recipes. The syntax description is proper crazy; gives Homespring a run for its money, easily, in the realm of metaphorical programming languages that embrace their metaphor.

-

"This recipe prints the immortal words "Hello world!", in a basically brute force way. It also makes a lot of food for one person."

Momentum

02 December 2008

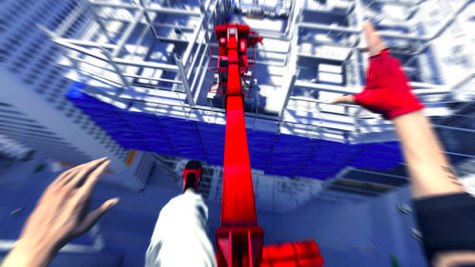

I’ve been trying to find a way into writing about Mirror’s Edge for about a month now, and during that time, the whole Reviewgate affair sprang up – in which Keith Stuart suggested that some of the reviews of Mirror’s Edge damning it with faint praise, and then suggesting that a sequel might solve some of its issues, might have got games criticism all wrong.

Trying to be critical around a game that kicked off another how-to-review-games (and what-are-games-anyway?) debate suddenly seemed even harder. But nagging at the back of my mind, was the need to write something. And then it made sense: the best way to approach the game was to come at it strictly from the angle of movement, and, more specifically, to examine its relationship to Parkour.

Mirror’s Edge is most notably for being a first-person game where shooting is pretty much optional and, a lot of the time, inadvisable. Instead, it places the act of motion itself front and centre: as Faith, a “runner” (the game’s parlance for traceur) you dart through the City as a free-running courier, free from the tight grips of a police state. Motion is the enemy of lockdown; running the alternative to putting up and shutting up.

I don’t really want to talk about technical aspects of the game very much, so it suffices to say that the engine and sensation of motion are remarkably well implemented; it realises the motion of not a camera at head height but a body superbly, not just showing you limbs at the camera’s extremities but genuinely making you feel like they belong to your character. It’s invigorating to play, and genuinely breathtaking to watch a skilled player navigate rooftops at speed. (If you’ve not seen the game, this is a good sampler).

But enough of that. What I really wanted to talk about was movement itself. Movement, and momentum.

As I played the game and went back (thanks to conversations with friends) to other writing on Parkour, the game’s first-person perspective made a lot more sense.

David Belle‘s comment on the physical aspect of Parkour is a good place to begin:

“the physical aspect of parkour is getting over all the obstacles in your path as you would in an emergency. You want to move in such a way, with any movement, as to help you gain the most ground on someone or something, whether escaping from it or chasing toward it.”

Whilst Parkour is, ultimately, an expressive form of movement, the aesthetic Belle suggests it strives for is one of minimalist elegance, rather than technical audacity. It’s not an activity for show-offs; the efficiency of movement takes priority over the way that movement looks.

Third-person games are great to show-off in. You can always see the player character on screen; it’s easy to understand how the motions the player undertakes with pad or stick translate into movement on the screen, and it’s easy to mentally connect the player to their avatar. Fighting games, notably, make for great spectator sports even for the unskilled spectator.

But by making Mirror’s Edge first-person, it takes the focus away from the aesthetics of motion and places them on the actual act itself – on the skill required. This makes it much less of a spectator sport – it’s always hard to engage with other people playing first-person games if you don’t know the game in question very well.

Mirror’s Edge forces you to approach the world as a runner or traceur, and take pleasure in the elegance and efficiency of your own movements, rather than the entertainment of others.

The game communicates it well through its tutorial. A fellow runner, Celeste, runs Faith through a few manoeuvres to get Faith back in shape after an accident. The advantage of this is that before the player performs each manoeuvre, they get to see it acted out by another character in the third person. Instead of being a form of showing off, this is a way of giving the player a mental model of what they look like in the world when they navigate it. After all, it’s initially quite confusing, relating the flailing hands and feet on screen to actions a character might undertake. Celeste’s demonstration helps to connect those dots. And in Faith and Celeste’s movements, we see another embodiment of Belle’s ideas around Parkour:

“The most important element is the harmony between you and the obstacle; the movement has to be elegant… If you manage to pass over the fence elegantly—that’s beautiful, rather than saying I jumped the lot. What’s the point in that?”

Belle knows that Parkour can’t just be purely functional, but it’s noticeable that elegant movement tends to lead to faster, smoother passages through the city. And that’s why it’s very noticeable that, despite the emphasis on maintaining momentum and speed throughout levels, Faith is never anything less than gracious in her movements. When her movements become ugly – taking heavy falls, slipping and missing a jump, pulling herself up onto a ledge – they tend to become slower, too.

Mirror’s Edge strives for a more internal understanding of what is beautiful and satisfying within it. Any notion of “showing-off” in the game is confined not to a third-person replay camera, to fetishise the movements of the runners, but to a time-attack mode, where players face off against one another. They are not comparing the aesthetics of the run, but their technique. To borrow a term from martial arts, Parkour is an internal art, and Mirror’s Edge captures that far better than I think many have commented on. It captures the subjectivity of the art not only in its first-person camera, but in its “Runner Vision”, that colours optimal paths through the level with subtle red tints. At times, though, it’s never clear if these are hints or actual objects – the iconic red cranes may well be red, and the coincidence of an environment that demands to be run through highlighting itself is a pleasing one.

It also captures a core idea of games: that movement itself can be fun, especially when moving inside the body of someone who is superior in ability or capacity than the player. Moving through Faith’s world is, at times, a massive amount of fun; it brings to mind a chain of motion through videogames, from charging through levels with B button jammed down as Mario to Sonic’s indestructible careering through Green Hill Zone. The ability to experience that in a much more realistic world is genuinely invigorating.

And momentum becomes a key concept within the game.

In a post I keep linking back to, Iroquois Pliskin explains that the key feature of Survival games is the conservation of limited resources. In Mirror’s Edge, that resource is not ammunition or open ground, but momentum; when you have it, your flight from the security forces is much easier than without it.

Which is why it’s such a shame that the game seeks to tear momentum from the player so often. Whilst the rooftops are reasonably straightforward to navigate with heat on your tail, the interiors are often confusing. Taken slowly, it would not take long to find optimal routes through them – but when you’re being chased by guards with submachineguns, who have the power to drain momentum from you with a single blow or shot, the stakes become much higher. And, of course, when you make those slow, clumsy maneouvres mentioned earlier, you feel as if you’ve failed. Faith should be nothing less than graceful in her movements, and for much of her flight, I made her barely perfunctory. I was letting her down.

And perhaps the worst momentum-killer is the game’s story. The plot itself is fine – the back of the game’s box is lucid in its brevity:

In a city where information is heavily monitored, where crime is just a memory, where most people sacrifice freedom for a comfortable life, some choose to live differently.

They communicate using messengers called Runners.

You are a Runner called Faith.

Murder has come to this perfect city and now you are being hunted.

That feels ideally suited to the fast-paced, no-nonsense world of the runner. In the game itself, however, this turns into a twin sister on the other side of the law, private security forces with too much power, and an awful lot of cutscenes.

The game’s story is at its best when expressed through the environment and motion. At one memorable point, you discover that the police are countering the Runners by training the officers to becomes Runners themselves. You stumble upon a training ground for police-runners; it’s a room built into what looks like an old silo, with a well-designed training course inside it. At the beginning of the game, it might have been a good tutorial, but now you can ace it. The wall has 05 daubed on it, indicating this is part of a more comprehensive training programme.

It’s a nice piece of environmental storytelling – and you have all of twenty seconds to take it in, because you are being chased by two police-runners. I’m not sure everyone will have picked up the subtlety in that room, and it’s a shame, because it’s a really important moment; instead, you focus on the cops on your tail, and run for the next red door at top speed. Similarly, whilst the flat-animated cutscenes provide a lot of exposition, they lack the emotional power of the two highly memorable in-game cutscenes (one about halfway through, and one right at the end) that demonstrate that DICE really do understand this whole first-person camera thing.

Mirror’s Edge is at its best in moments of free exploration, finding new paths over serene rooftops, feeling that sense of flow as you tuck your feet over a barbed-wire fence; when it captures the feeling of a body moving, be it through graceful falls or being violently hurled off a building by a former wrestler; feeling like you’re flying across the city.

It’s at its worst when, unlike on the rooftops and in the stormdrains, it places obstacles in its path – narrative, out-of-engine cutscenes, action-through-havoc that you can’t escape.

And especially when it makes you fail: Faith is clearly an experienced runner, and there are times where the player can’t live up to their avatar’s abilities. DICE choose to present that in binary success or failure, which has lead to criticisms of trial and error. Perhaps; at the same time, I’ve never encountered a single glitch or unrealistic motion throughout all my travels through the game. The coherence of the illusion is remarkable, and the price for that coherence is a definite kind of failure at times. I am not sure that’s necessarily a good enough excuse for some of the stop-start, but I feel that the coherence of the game’s illusion is something that isn’t praised enough. If only that could be provided without such a sensation of failing – not as a player, but failing the character you play.

It brings to mind Jump London. If there’s one thing Mirror’s Edge gets right, it’s the feel of the city under your feet. Faith doesn’t just exist as a character in a cutscene or as four disembodied limbs; she lies in the seams between her trainers and the concrete.

If anything’s emerging from all the coverage the game – and criticism of it – is getting, it’s that it is not for everybody, and perhaps that Marmite-y nature will prevent it having greater success. But whether or not it is good or bad, you need to understand that it is important. Other games have attempted similarly visceral first-person experiences, and they are few and far between: Trespasser was flawed, far more fatally than Mirror’s Edge; Breakdown wasn’t very good at all; and the excellent Chronicles of Riddick, made a very different use of first-person, primarily using it as a characterisation tool for a slower-moving but more powerful protagonist. Mirror’s Edge really is something new, and something different, and something that countless games and designers are going to learn from in the next few years.

And it’s for that reason you need to play it. It takes one of the earliest videogame-mechanics – moving from A to B past obstacles – and implements it not only in a 21st century manner, but places it at the heart of its philosophy. Not only that, it places it into a world that resonates vibrantly with that of the traceur: one of lines hidden through cities, playgrounds hidden in architecture, and resistance hidden in motion.