-

"But, I also think that in our efforts to define and legitimize our practice as a professional discipline we sometimes forget the history we inherit, the legacy of games made by communities of players, games made by amateurs, by dilettantes, by mathematicians, mothers, scientists, gym teachers, shepherds, inventors, philosophers, eccentrics and cranks.

And in honor of this tradition I would like to suggest other verbs for us to describe where games come from, alternatives to the overconfident precision of the word “design”. Words like invent, discover, compose, write, find, grow, perform, build, support, identify, copy, re-assemble, excavate and preserve." So much good thinking in this post from Frank Lantz

-

"Its weird really. You’re standing there in front of something, perhaps its an ancient artefact, buried for thousands of years – perhaps its a mummy, partially unwrapped. A real human being, you can see their face from all those years ago, see how they lived, what they ate. History, right there… But whatev’s. Look! There’s a telly over there!" Yep.

-

Brian Sutton-Smith has died; this is a solid – and impressive – obituary.

Putting the nuclear option front-and-centre

15 January 2015

I was talking to Tom and some other people at Matt’s coffee morning this morning, and I mentioned a tiny piece of interaction design I was fond of (that was pertinent to our conversation). Tom said ‘write that up so I can point to it‘, so that’s what I’m doing.

A long while ago, at an agency job, I was sketching out wireframes and interactions for a web-based feed reader. It was designed for users who possibly weren’t that used to RSS, and so it needed to guide them a bit through the best practices of interactions.

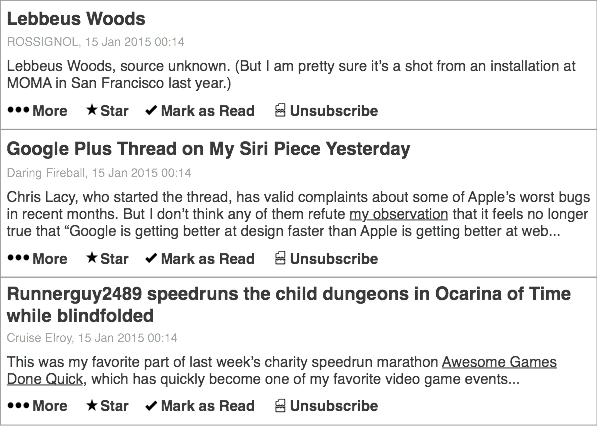

The list of articles looked a bit like this:

Pretty standard, although the important component was the unsubscribe button.

I put an unsubscribe button on every feed item.

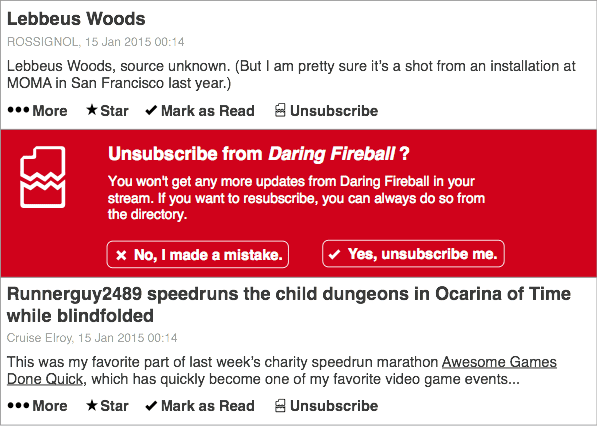

I wanted to stress that if you weren’t enjoying a feed, you didn’t have to read it. Just bin it! You’ll be a lot happier. Clicking the unsubscribe button would do something like this:

to indicate the severity of your action. I felt that was reasonable – little button, big confirm dialogue. And then boom: the entire feed is gone.

It’s amazing how often you can mark an item as read, or archive an email, before committing to unsubscribing. I wanted to capture how ephemeral subscriptions could be. They weren’t commitments; they were just things you’re interested in.

I think the me-of-2015 would also ensure that there was a way of triggering this interaction based on patterns of behaviour. For instance, asking the user if they want to unsubscribe from a feed if they’ve marked it as read a surprisingly short time after they looked at it (indicating they hadn’t read an entry). And, similarly, checking a few weeks later that you didn’t want to subscribe back: frequently, I unsubscribe from things just because I need a break, or I don’t have the space – not because I want them gone forever.

It’s very easy to offer final, decisive actions; they’re very native to dialogue boxes, buttons, and digital systems. But some things are ephemeral, and it’s important to stress that in design. Just because I unsubscribe form a feed, or unfollow someone on Twitter, doesn’t mean it’s final: I might want it back one day; I might be taking a break from my higher-traffic friends. I wanted to try encouraging that.

And I wanted to remind users that there was an alternative to ‘inbox overload’: you could just have a break.

In these two stills, drawn a bit from memory, there’s a lot of gaps – and I’ve not sketched any of the possible animation or motion that would help convey what was going on. Still, that interaction – offering what feels like the nuclear option front and centre, reminding the user that it isn’t a nuclear option – I quite like that.

-

"keep some parts of myself severely to myself, am thus able to maintain a deep fruitful disjunction between this real world & the real real world." (and: of _course_ the "Robin" commenting on MJH's blog is Robin Sloan)

-

"The lineage of luxury in art – from lapis lazuli, to bronze casting, gold plating or diamond encrusting – extends now to graphics cards, ray-tracing, skin rendering, reflection mapping and to processor speeds, hyperthreading, render farms and the complex world of outsourcing, government subsidies or mineral extraction. It’s important and interesting! Curators take note!" This is good / the Ed Atkins also sounds good.

-

Bookmarked for reference – Dan's lists are usually good.

-

Beautiful. (via Denise).

-

"King Lear would have killed it in Silicon Valley." More Maciej, and yes, it's great.

-

These are also good. And funny.

-

Seems like a reasonable set of tools to help out with this.

-

"MailCatcher runs a super simple SMTP server which catches any message sent to it to display in a web interface. Run mailcatcher, set your favourite app to deliver to smtp://127.0.0.1:1025 instead of your default SMTP server, then check out http://127.0.0.1:1080 to see the mail that's arrived so far." Useful!

-

"The reason I am able to make Twitter bots is because I have been programming computers in a shitty, haphazard way for 15 years, followed by maybe 5 years of less-shitty programming. Every single sentence in the big preceding paragraph, every little atom of knowledge, represents hours of banging my head up against a series of technical walls, googling for magic words to get libraries to compile, scouring obscure documentation to figure out what the hell I’m supposed to do, and re-learning stuff I’d forgotten because I hadn’t used it in a while." This paragraph also represents my experience of both programming and how I write my toys; a slightly round-about set of experience to get to where we are now, with lots of reading the manual and doing things in dumb ways occasionally. Programming!

-

Yep, this all seems like a very good list to me. Filed away for the next time I have to do anything with maps.

-

Enjoyed this a lot: Kim Stanley Robinson on California, SF, and the relationship between the two. For me, timely.

-

"In this film I wanted to look beyond the childish myth of ‘the cloud’, to investigate what the infrastructures of the internet actually look like. It felt important to be able to see and hear the energy that goes into powering these machines, and the associated systems for securing, cooling and maintaining them." Looks beautiful: Timo's customary look in enveloping, three-screen 4K. Gosh. Also: the uses of stills-as-film is really interesting to me at the moment.

-

"One-thousand dollars invested at a 20% discount with 5% interest (calculating interest every 3 turns, but simple, not compounding interest) means a player will have starting debt of $1000. After three turns the debt is $1050, 6 turns is $1100, 9 turns is $1150, etc. Totally manageable. The banker is your friend and wants you to succeed."

-

A lovely game – almost a poem, but definitely Enough Game – by Holly Gramazio, about being a blackbird in a city. It made me feel many things, which is what the best writing does. Also, I shall now probably play it again.

-

"We foresee an amazing future where not only can your household devices communicate with each other, they can also communicate with us over the same Internet lines. How cool would it be if your fridge could post a Medium here on Medium every time it needed you to buy more milk? And that’s just one idea." There are many more ideas in this post.

-

"We need to be armed not only with outrage at the intrusion but with the opinion that every financially motivated imposition is a missed opportunity to enhance the city we live in. Services on our streets are always in change, post boxes and pay phones are becoming antiquated, but there is a real and exciting potential for these spaces to become something else, something human, something exciting and most importantly, something for us." Cracking post from Ben about Renew's bins, some of what we learned in Hello Lamppost, and how people do – and could – engage with the cities they live in.

-

"The least important question you can ask about Engelbart is, "What did he build?" By asking that question, you put yourself in a position to admire him, to stand in awe of his achievements, to worship him as a hero. But worship isn't useful to anyone. Not you, not him.

The most important question you can ask about Engelbart is, "What world was he trying to create?" By asking that question, you put yourself in a position to create that world yourself."

-

"It has some unique perspective every once in awhile, but honestly, America can be super derivative. Most of the stories have already been on The Simpsons."

Toca Builders, and the spirit of Seymour Papert

23 June 2013

I’ve been playing a little with Toca Boca‘s latest iOS toy: Toca Builders.

As you’d expect from Toca Boca, it’s charming: a straightforward, paired down implementation of an idea, with unambiguous UI and lovely character design.

Builders is Toca’s take on a block construction toy for small children. Initially, it might seem a bit clunky, a Minecraft pastiche that’s not nearly so sophisticated as Mojang’s original. After all, it’s a tiny play area compared to Minecraft – six blocks of height and relatively small X-Y dimensions.

It’s the plural in the title that makes it so interesting, though: builders. This is not (just) a game in which the user is a builder; it is a game about six individual builders (pictured above). Each has their own different ability: most can both construct and desturct; almost all can control the colour of blocks; some are better at changing blocks after the fact, others at sketching with. They each control slightly differently – and they each manifest in the landscape. You can swap between builders with a simple or menu, or by tapping on any that you can see.

It’s the manifestation and personification of the four builders that suddenly clicked for me. As I played this, I realised what it really was: Minecraft through the eyes of Seymour Papert. Lego as LOGO.

Papert explained the LOGO turtle as an “object-for-thinking-with“. Not just a device to command, attached to a programming language; a device that you see the world through. Or as Papert says in Mindstorms, his wonderful book about the development and intent behind LOGO:

“objects in which there is an intersection of cultural presence, embedded knowledge, and the possibility for personal identification.”

He makes what I think is a clearer point later, though, and which I think Toca Builders captures perfectly:

Even the simplest Turtle work can open new opportunities for sharpening one’s thinking about thinking: Programming the Turtle starts by making one reflect on how one does oneself what one would like the Turtle to do. Thus teaching the Turtle to act or to ‘think’ can lead one to reflect on one’s own actions and thinking. And as children move on, they program the computer to make more complex decisions and find themselves engaged in reflecting on more complex aspects of their own thinking.

Papert is sometimes quite wordy. When I explain this to people, I tend to say: the value of the Turtle is that when you are stuck, you solve the problem by pretending to be the Turtle. This is especially valuable for young learners; as Papert points out later:

Children can identify with the Turtle, and are thus able to bring their knowledge of their bodies and how they move into their work of learning formal geomtetry

There are some lovely photos in Mindstorms of kids on a playing field, practicing Logo; one of them is being the Turtle, and the others are telling her what to do. The second you act out a program for yourself (or watch another child follow your instructions to the letter), you see how literal you need to be, or which line of code is ambiguous. You begin to see how the computer processes information (“thinks” being, unfortunately, an entirely inaccurate word).

This kind of embodied representation of computational logic is very rare. Often, the hard things in computer science are very abstract. I do not know how to “pretend to be the compiler”; I just have to trust input and output.

Toca Builders takes the abstract building of Minecraft – tools attached to a disembodied perspective (albeit one hindered by some degree of personhood – factors such as gravity, and so forth) – and embodies them to help younger children answer the question which tool would you use to place a block where you need to? Or sometimes backwards: which block shall we place next? It is not quite as freeform as Minecraft, but it actually forces the user to think a little harder about planning ahead, lining up his builders, and which builders go together well. Measure twice, cut once.

To that end, it’s much more like real-world building.

Papert was very clear about one particular point: the value of this is not to think in mechanical ways; it’s actually the opposite. By asking children to think in a mechanical way temporarily, they end up thinking about thinking more: they learn that there are many ways to approach a problem, and they can choose which way to think about things; which might be most appropriate.

And so Toca Builders is, in many ways, like all good construction toys: it’s about more than just building. It’s about planning, marshalling, making use of a limited set of tools to achieve creative goals. And all the while, helping the user understand those tools by making them appear in the world, taking up space in it, colliding with one another, and needing moving. All so that you can answer the question when you’re stuck: well, if you were Blox the Hammer, what would you do?

Some of what looks like clunkiness, then, is actually a subtle piece of design.

If you’re interested in the value of using computers to teach – not using computers to teach about computers, but using computers to teach about the world, then Mindstorms is a must-read. It’s easy to dismiss LOGO for its simplicity, and to forget the various paradigms it bends and breaks (more so than many programming languages) – and it’s remarkable to see just how long ago Papert and his collaborators were touching on ideas that are still fresh and vital today.

-

A great post on the detailed design of an iOS app; I particularly like the focus on animatics, and also on rearranging the screen rather than always swiping to a new one; it's a thing I've sketched before.

-

Physical artefacts that respond as expected to touchscreen gestures.

-

"Araucaria… has 18 down of the 19, which is being treated with 13 15". How very, very sad; what a way of telling the world.

-

This is marvellous: Tog on magic and software, and what one can teach the other. The stuff about perceived time periods, and also on distraction, is particularly great. It's not just about the functionality: it's about how you present it; showmanship all the way down. (And: I like the reminder about the kinds of honesty that are important, in order that dissimulation still works0.

-

Excellent, thoughtful article from John Allspaw on what experience in software engineering really looks like. Valuable reading both for software engineers, and also for the people who work with them.