-

"Sentiment analysis tool for node.js based on the AFINN-111 wordlist." Interesting; feel slike it could be ported to other platforms, too.

-

"Micro-frameworks are definitely the pocketknives of the JavaScript library world: short, sweet, to the point. And at 5k and under, micro-frameworks are very very portable. A micro-framework does one thing and one thing only — and does it well. No cruft, no featuritis, no feature creep, no excess anywhere. Microjs.com helps you discover the most compact-but-powerful microframeworks, and makes it easy for you to pick one that’ll work for you." Ooh, nice.

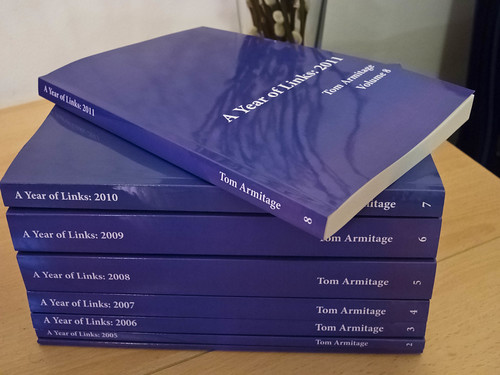

A Year of Links

26 February 2012

I made a book.

Or rather, I made eight books.

If you’ve read this site for any particular length of time, you’ll be aware that I produce a lot of links. Jokes about my hobby being “collecting the entire internet” have been made by friends.

I thought it would be interesting to produce a kind of personal encylopedia: each volume cataloguing the links for a whole year. Given I first used Delicious in 2004, that makes for eight books to date.

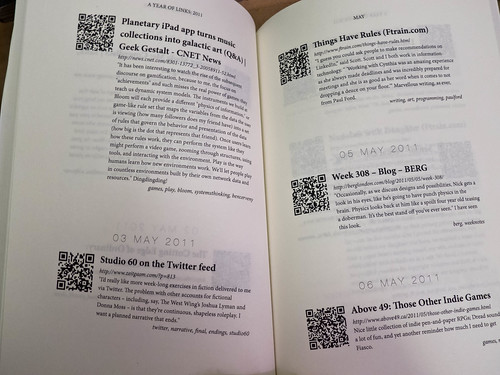

Each link is represented on the page with title, URL, full description, and tags.

Yes, there’s also a QR code. Stop having a knee-jerk reaction right now and think carefully. Some of those URLs are quite long, and one day, Pinboard might not exist to click on them from. Do you want to type them in by hand? No, you don’t, so you may as well use a visual encoding that you can scan with a phone in the kind of environment you’d read this book: at home, in good lighting. It is not the same as trying to scan marketing nonsense on the tube.

Each month acts as a “chapter” within the book, beginning with a chapter title page.

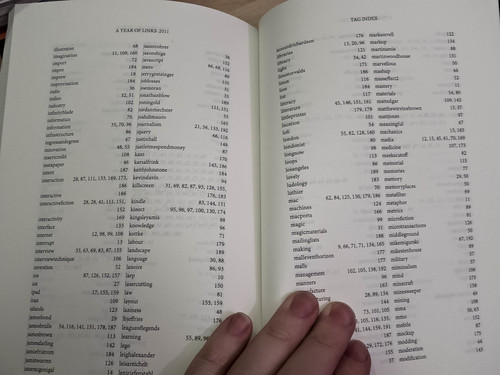

Each book also contains an index of all tags, so you can immediately see what I was into in a year, and jump to various usage.

Wait. I lied. I didn’t make eight books. I made n books. Or rather: I wrote a piece of software to ingest an XML file of all my Pinboard links (easily available from the Pinboard API by anyone – you just need to know your username and password). That software then generates a web page for each book, which is passed into the incredible PrinceXML to create a book. Prince handles all the indexing, page numbering, contents-creation, and header-creation. It’s a remarkable piece of software, given the quality of its output – with nothing more than some extended CSS, you end up with control over page-breaks, widows and orphans, and much more.

The software is a small Sinatra application to generate the front-end, and a series of rake tasks to call Prince with the appropriate arguments. It’s on Github right now. If you can pull from Github, install Prince, and are comfortable in the terminal, you might find it very usable. If you don’t, it’s unlikely to become any more user-friendly; it’s a personal project for personal needs, and whilst Prince is free for personal use, it’s $4800 to install on a server. You see my issue.

So there you are. I made a machine to generate books out of my Pinboard links. Personal archiving feels like an important topic right now – see the Personal Digital Archiving conference, Aaron and Maciej’s contributions to it, not to mention tools like Singly. Books are another way to preserve digital objects. These books contain the reference to another point in the network (but not that point itself) – but they capture something far more important, and more personal.

They capture a changing style of writing. They capture changing interests – you can almost catalogue projects by what I was linking to when. They capture time – you can see the gaps when I went on holiday, or was busy delivering work. They remind me of the memories I have around those links – what was going on in my life at those points. As a result, they’re surprisingly readable for me. I sat reading 2010 – volume 7, and my proof copy – on the bus, and it was as fascinating as it was nostalgic.

Books also feel apposite for this form of content production. My intent was never to make books, not really to repurpose these links at all. And yet now, at the end of each year, a book can spring into life – built up not through direct intent, but one link at a time over a year. There’s something satisfying about producing an object instantly, even though its existence is dependent on a very gradual process.

So there you have it. I made a book, or rather eight books, or rather a bottomless book-making machine. The code is available for you to do so as well. It was hugely satisfying to open the box from Lulu at work one morning, and see this stack of paper, that was something I had made.

-

Installing Redis on Linode.

-

"RequestBin lets you create a URL that will collect requests made to it, then let you inspect them in a human-friendly way. Use RequestBin to see what your HTTP client is sending or to look at webhook requests." Which is very useful.

-

"It's sort of a no-brainer. And a fascinating way to think about creating a sustainable source of income to allow, even in part, artists to produce works are genuinely expensive in time and cost to create. It should also prove to artists, and anyone who frets over the illusion of print rights, that they've got nothing to worry about. This stuff is an entirely other material and colour made of light, it turns out, doesn't just magically translate to colour made of pigment the way that, say, a word-processing document does. And if anyone is really going to lose sleep over the people who are already predisposed to print things out on their shitty homes printers my only advice is to give up now. Let them and understand that there are more interesting problems to solve and if projects like 20×200 are any indication there's a whole world of people who want to help with not only their moral support but their wallets." Aaron on the Hockney show, subscription app art, and drawing on iPads.

-

"This gem is a C binding to the excellent YAJL JSON parsing and generation library." Ooh, JSON stream-parsing.

-

"If school programming languages that serve children best end up looking quite a bit different from conventional programming languages, maybe it’s actually the conventions that need changing." Several good points from Alex, and some good points about breaking away from equating "computational" with "procedural".

-

"I could argue back and forth forever, but what I really want to do as a developer, is to work on games in tiny, tiny teams. It means less compromise when it comes to design. It means more freedom when it comes to implementation."

-

"Shim is a node.js-based browser-compatibility tool that lets you synchronize several devices/browsers and surf the same pages simultaneously on all of them." Wow.

-

An Impressive list of notable examples of programmatic journalism from Dan Sinker; something I must return to.

Drivetime Spotify App

04 December 2011

Music Hack Day London this weekend. Tom, Blaine and I ended up making a thing which didn’t demo perfectly, called Drivetime.

It solves a common problem: how do I listen to the same classic pop and rock anthems on a Friday afternoon as people in other studios? The answer is with the Drivetime app.

Drivetime is a Spotify app. You drag a playlist into it to start broadcasting – you set your station name with a simple text field. Then, anyone loading the app can click on your name and hear what you’re playing. Not just the current track – it’ll start the track for others at exactly the point you’re currently at, and it’ll advance through the playlist when a track finishes. At any point, you can stop listening, and choose another song to listen to.

That’s it, really: a simple broadcast/listen system, all built into Spotify as a native application.

The front-end is just HTML/CSS/Javascript, which is how Spotify apps are built; the communication with the client is via socket.io, on top of node.js on the server. Tom and Blaine wrote the back-end; I wrote a bunch of the front-end, which Blaine promptly made much better, and did all the hot pink neon. We all played a lot of Tina Turner in the hacking rooms, and we went home to bed betimes on the Saturday night.

All the code’s in github. The Spotify app only runs (at the moment) if you’re a Spotify developer. We might see if we can get it a bit further and release itspot, so people can listen to one another’s classic rock selections.

It was a fun hack, even if my explanation of it was incoherent, and part of a great weekend – so many superb hacks, large and small, on display.

-

"Takes a snapshot with your Mac's built-in iSight webcam every time you git commit code, and archives a lolcat style image with it." YES.

The Story of a Lost Bomber

23 January 2011

It was History Hack Day this weekend. My friend Ben Griffiths scraped the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s register to try to contextualise the death of his great-uncle in World War II.

Before you read on, please do read his story. It’s worth your time.

Ben’s hack is intelligent and, as ever, he explains it with precision and grace. But really, it wasn’t the hack I wanted to draw to your attention; it was the story he tells.

Like many hacks at such events, it begins with a data, scraped or ingested, and Ben’s plotted it over time, marking the categories his great-uncle is represented by.

But data over time isn’t a story; it’s just data over time. A graph; or, if you like, a plot. What makes it a story? A storyteller; someone to intervene, to show you what lies between the points, what hangs off that skeleton. Someone to write narrative – or, in Ben’s case, to relate history, both world and personal.

I’m left, after all this, thinking of just how young these bomber boys were. Looking at this data has been a much more moving exercise than I was expecting.

I found it very affecting, too, but not just because I was looking at the data: I was looking at it through the lens that Ben offered me in the story he told. When you consider it’s the story of one tragic loss amid 12,395 others, you pause, reflect, and try to perhaps comprehend that.

In the end, I couldn’t, entirely, but I tried – and because somebody told me just one story, about one individual, his plane, and his colleagues, I perhaps came closer to an understanding than I otherwise might have. And, because of that, I’m very grateful Ben shared that single story. I’d call that a very worthwhile hack.

-

Library to send appropriate pulses to an IR LED to trigger Nikon cameras

-

"TimedAction is a library for the Arduino. It is created to help hide the mechanics of how to implement Protothreading and general millis() timing. It is sutied for those actions that needs to happen approximately every x milliseconds." Aha.

-

"This library is a collection of routines for configuring the 16 bit hardware timer called Timer1 on the ATmega168/328." (Timers look hard).