-

"In publishing we now talk about immersive narrative, mainly because we are tense about the future of books. People who love reading are in it for exactly that: to soak themselves in story. To forget whenever possible that there even is a story outside the book, particularly the bubble-busting story of how the book was made. As a reader, I cling to the sense that this all but transcendent experience comes directly to me from one individual imagination. The feeling I have when reading fiction—of a single mind feeding me experience and sensation—is seldom articulated but incredibly powerful. As a reader, I don’t want fiction to be a group project." But, as the article points out, the role of the editor(s) means it always is. A lovely article about books, publishing and fiction.

Chip Kidd’s first novel, The Cheese Monkeys, has been perhaps my favourite book of the year so far. Not the best book I read, but definitely my favourite.

It’s about a young man attending art school in late 50s America, and discovering graphic design, through a particularly memorable course – Art 127, Introduction To Graphic Design, run by one Winter Sorbeck.

I liked it for many reasons, including Kidd’s deft use of language, its acidic humour, and a description of being drunk – and then hungover – that comes close to Lucky Jim‘s. But I think I liked it most because it reminded me of the values of art school that I’ve come – very much secondhand – to appreciate. Namely: the value of the crit.

More specifically: the value of disassembly – taking apart things you know and learning how to start from nothing. Taking apart a problem to find the only appropriate answer (though there may, in fact, be many). The value of being challenged to do difficult things, and honing skills. The value of physical skills – literal muscle control – in an era before the technological overhaul of design (and the value, as ever, of being able to draw. Even just trying to draw. It helps me a lot).

And, most notably, the value of criticising the Work as the Work.

In a crit, the work may be praised, it may be criticised, it may be torn into tiny pieces, fisked until there is nothing left of it. But it is only a criticism of the Work. It is not personal, and it only criticises the Worker in so much as it criticises their efforts and production on this work. It is a magic circle for being able to critically discuss a work.

As Sorbeck’s students find, it is difficult to learn how to be in a crit, difficult to learn how to respond to one, and difficult to learn how to give one. But it’s all valuable: it is focused on making the work better. There is a degree of building a thicker skin about work required – but also a degree of understanding the difference between criticism and complaining, criticism and anger.

I went to see Bauhaus: Art As Life at the Barbican last week, and The Cheese Monkey’s fictional version of the process of learning how to see was very relevant to my reading of that exhibition: seeing an institution begin to create the beginnings of what we now see in foundation art courses around the world. I was most glad to see the early output of the foundation years at the Bauhaus – some really exciting work made by artists learning how to see form, colour, material, and texture again. The Bauhaus reminded me of all the reason’s I enjoyed Kidd’s book.

I could have dog-eared most of the second half of the book – classroom scenes and narrative alike – but there were three quotations I did end up marking, so as usual, time to share them on the blog.

p. 79, in which the narrator meets Himillsy’s architect boyfriend:

He put out his hand.

“Garnett Grey.”

Yes, Garnett Grey was an Architect. Were a psychoanalyst to approach him from behind, tap his shoulder, and say “Humanity,” Garnett’d spin around, and respond, without hesitation, “Solvable.”

p. 106, in which Winter Sorbeck explains why the title of his course – Introduction To Graphic Design – has been retitle from the Introduction To Commercial Art that is listed in the course programme.

“…I’ve been put in charge of the store here, and I say it’s Introduction To Graphic Design. The difference is as crucial as it is enormous – as important as the difference between pre- and postwar America. Uncle Sam… is Commercial Art. The American flag is Graphic Design. Commerical Art trys to make you buy things. Graphic Design gives you ideas. One natters on and on, the other actually has something to say. They use the same tools – words, pictures, colors. The difference, as you’ll be seeing, and showing me, is how.”

p.177, Winter on design and power.

“Kiddies, Graphic Design, if you wield it effectively, is Power. Power to transmit ideas that can change everything. Power that can destroy an entire race or save a nation from despair. In this century, Germany chose to do the former with the swastika, and America opted for the latter with Mickey Mouse and Superman.”

It’s a lovely book. I had a lot of fun with it.

-

David Markson left all the books he owned to New York's Strand bookshop; now, they are likely further spread. This blog collects annotations and commentary that people have found in books previously belonging to Markson. Brilliant.

-

"That’s why I like having these little printed books, or these little files of my notes, because I can literally pull up anything I want to remember from Moby Dick, and in repeating it, remember it. Annotating becomes a way to re-encounter things I’ve read for pleasure." Which is why I have a stack of eight books on my dining table, and more to come over the years – to be read, not just hoarded.

-

"Melville’s searing, wayward novel about obsession and the nature of evil becomes a twin-stick shooter for consoles. The twist? The playing field is 5000 miles wide, and there’s only one enemy." Christian is brilliant. (I'm pretty sure my links are full of 'Christian is brilliant' annotations)

-

"Or, in a diffirent formulation of the legendary author of Sim games Will Wright, "Playing the game is a continuous loop between the user (viewing the outcomes and inputting decisions) and the computer (calculating outcomes and displaying them back to the user). The user is trying to build a mental model of the computer model.""

A Year of Links: Your Questions Answered!

04 March 2012

Following writing about my books to catalogue each year of my bookmarks, several readers had questions, which (rather than responding to in a comments thread), I thought I’d get around to here.

- Matt Edgar commented on the thickness of the spines, and what they represented in terms of my time/attention each year. All I can say is: I got a bit better at the process (more on this later) as time went on; I got quicker at both reading and writing. Also, during my time at Berg (2009-2011), part of my job was writing and researching, so the size of those volumes is in part because I had deliberate time during my work for reading and bookmarking.

- James Adam asked if the body text is from Pinboard or the page. It’s usually a combination of both, with the majority being a salient quotation.

If you’ve ever seen the format I use for my links, it tends to be a long quotation followed by a single line or two. James mentioned this because it seemed like a lot of writing. To which my answer is: it is and it isn’t. It’s a lot of words, but most of them aren’t mine.

To explain, it’s probably worth talking a little about how I bookmark:

I have the Safari extension for Pinboard installed. When I’m reading a page I like, or have found useful, I highlight a particularly salient quotation and click the extension button. This loads the Pinboard form with the contents of the clipboard loaded into the body copy field. I then wrap it in quotation marks, and perhaps add the first line or two of commentary that comes into my head. Then, I fill out the tags – as fast as I can, with the first thing that comes into my head. This tends, for me, to be the most valuable way of tagging.

The time-consuming part is reading the articles; I try to make bookmarking as lightweight as possible.

Bookmarks are published to this site via Postalicious.

So: whilst it looks like a lot of content, most of it is not mine, but it is copied/pasted into Pinboard. Really, though, I’ve got this down to a fine, swift art.

- In answer to Joel and Dave: I used Lulu for printing. I simply uploaded the completed PDFs to them for the inners. The covers were made in Photoshop, a bit by hand, and a lot by maths (because I wanted to use the same typeface on the cover that I do in the book.

- Justin Mason asked about cost. The first book, which is the pamphlet at the bottom for 2004, is about 30 pages, and cost around £2. The largest volumes – 2008/2009 – cost £7 or £8. 2010, which is volume 7, and my first proof of concept, was about £4.50. It was about £30 for the lot, plus delivery, though I saved a bit through some canny Lulu discount codes that I had.

And, finally, a big shout-out to Les Orchard, as the first person who wasn’t me to get the code up-and-running and make some books!

A Year of Links

26 February 2012

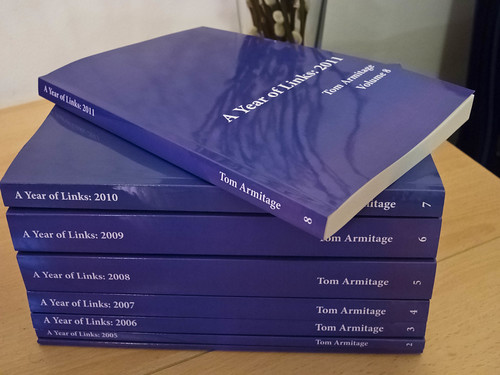

I made a book.

Or rather, I made eight books.

If you’ve read this site for any particular length of time, you’ll be aware that I produce a lot of links. Jokes about my hobby being “collecting the entire internet” have been made by friends.

I thought it would be interesting to produce a kind of personal encylopedia: each volume cataloguing the links for a whole year. Given I first used Delicious in 2004, that makes for eight books to date.

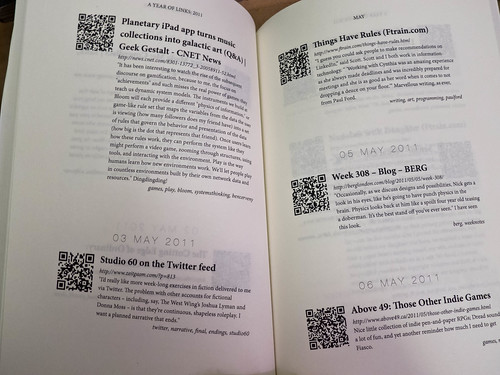

Each link is represented on the page with title, URL, full description, and tags.

Yes, there’s also a QR code. Stop having a knee-jerk reaction right now and think carefully. Some of those URLs are quite long, and one day, Pinboard might not exist to click on them from. Do you want to type them in by hand? No, you don’t, so you may as well use a visual encoding that you can scan with a phone in the kind of environment you’d read this book: at home, in good lighting. It is not the same as trying to scan marketing nonsense on the tube.

Each month acts as a “chapter” within the book, beginning with a chapter title page.

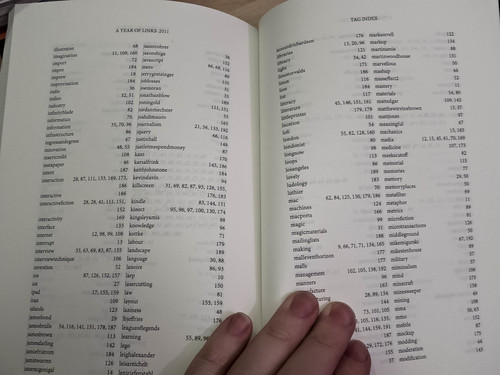

Each book also contains an index of all tags, so you can immediately see what I was into in a year, and jump to various usage.

Wait. I lied. I didn’t make eight books. I made n books. Or rather: I wrote a piece of software to ingest an XML file of all my Pinboard links (easily available from the Pinboard API by anyone – you just need to know your username and password). That software then generates a web page for each book, which is passed into the incredible PrinceXML to create a book. Prince handles all the indexing, page numbering, contents-creation, and header-creation. It’s a remarkable piece of software, given the quality of its output – with nothing more than some extended CSS, you end up with control over page-breaks, widows and orphans, and much more.

The software is a small Sinatra application to generate the front-end, and a series of rake tasks to call Prince with the appropriate arguments. It’s on Github right now. If you can pull from Github, install Prince, and are comfortable in the terminal, you might find it very usable. If you don’t, it’s unlikely to become any more user-friendly; it’s a personal project for personal needs, and whilst Prince is free for personal use, it’s $4800 to install on a server. You see my issue.

So there you are. I made a machine to generate books out of my Pinboard links. Personal archiving feels like an important topic right now – see the Personal Digital Archiving conference, Aaron and Maciej’s contributions to it, not to mention tools like Singly. Books are another way to preserve digital objects. These books contain the reference to another point in the network (but not that point itself) – but they capture something far more important, and more personal.

They capture a changing style of writing. They capture changing interests – you can almost catalogue projects by what I was linking to when. They capture time – you can see the gaps when I went on holiday, or was busy delivering work. They remind me of the memories I have around those links – what was going on in my life at those points. As a result, they’re surprisingly readable for me. I sat reading 2010 – volume 7, and my proof copy – on the bus, and it was as fascinating as it was nostalgic.

Books also feel apposite for this form of content production. My intent was never to make books, not really to repurpose these links at all. And yet now, at the end of each year, a book can spring into life – built up not through direct intent, but one link at a time over a year. There’s something satisfying about producing an object instantly, even though its existence is dependent on a very gradual process.

So there you have it. I made a book, or rather eight books, or rather a bottomless book-making machine. The code is available for you to do so as well. It was hugely satisfying to open the box from Lulu at work one morning, and see this stack of paper, that was something I had made.

-

"As a novelist, his ludic delight in finding new ways of playing with language — new ways of narrowing the ever-descending phalanx of cliché — is palpable in every sentence. So for all its contextual aberrance, this strange and disreputable book actually makes a certain kind of warped sense. And if for some reason you happen to be looking for a guide to arcade games of the early 1980s, you could probably do a lot worse." I knew of the book already – but this is a striking look at it.

-

"Fountain is a plain text markup language for screenwriting." More plaintext formats for writing in. This is good.

-

"When I'm evaluating entrepreneurs and their ideas, I look for "innovation bipolarity," a version of F. Scott Fitzgerald's first-rate intelligence: "the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function." Entrepreneurs should be able to argue passionately that their idea will change the world, and then, without skipping a beat, honestly assess the risks standing in the way of its success and describe what they are doing to mitigate them."

-

"I wanted to make the ship move, and I wanted to make it speak, and I wanted to speak back to it, with it, together. To make something." The poetry of creation is important. Also, @shipadrift is lovely, but you already knew that.

-

More useful vim stuff.

-

"In my forthcoming book Alien Phenomenology, at the start of the chapter on Carpentry (my name for making things that do philosophy), I talk about the chasm between academic writing (writing to have written) and authorship (writing to have produced something worth reading). But there's another aspect to being an author, one that goes beyond writing at all: book-making. Creating the object that is a book, that will have a role in someone's life—in their hands or their purses, around their mail, in between their fingers. Now, in this age of lowest common denominator digital and POD editions, it's time to stop writing books and to start making them." I am not totally sure I buy all of Bogost's argument, but I like his points explaining the role of artefacts. However, POD is weirder than he gives it credit.

-

"[Was shooting The Artist very different to making a 'regular' movie?] No, it’s a regular picture. The only difference is, there is no boom mic. And the story is not being told by what comes out of your mouth. If you want to tell the story, the story being the narrative, not the plot—the plot’s fairly simple—but if you want to tell the narrative, then you have to be concise with your reaction, and let the reaction get into your body and your face in a way you don’t necessarily do when you have dialogue, because the dialogue takes care of that." James Cromwell interview by the AV Club. I enjoyed this line especially.

-

"Mutual misunderstanding was not a new topic in fiction — or even in children’s fiction — but surely few explored it with Mayne’s insight, humour, gentle delicacy or subtlety: how children are not party to adult agendas, compromises, habits and assumptions; and of course vice versa, that in growing up adults have very often lost or set aside a valuable way of seeing the world. That there’s a thread of trust that marks the path everyone is treading, and that this thread is sometimes very fragile indeed. Can sympathetic intelligence and wisdom — wisdom precisely about such trust — sit alongside deep selfishness and a capacity to abuse? Well, yes, sometimes I think it can." Complex, thoughtful piece about William Mayne and difficult questions.