-

"This site contains the original source code for Elite on the BBC Micro, with every single line documented and (for the most part) explained."

Assembly is, it turns out, dark, dark magic. This is a very impressive thing to pore over – like Lions' Guide, but for Elite.

-

Simon Katan on teaching peripheral skills around computing, computation, and code. I agree wholeheartedly with his description of tools that shield users from complexities to the extent of hiding how things actually work. I also loved his idea of "flour babies for looking after code properly".

-

Filed away as a nice introduction to computational sensing, vision, and how computers don't see.

planetary, a sequencer.

01 March 2020

I wrote a music sequencer of sorts yesterday. It’s called planetary.

It looks like this:

and more importantly, it sounds and works like this:

In short: it’s a sequencer that is deliberately designed to work a bit like Michel Gondry’s video for Star Guitar:

I love that video.

I’m primarily writing this to have somewhere to point at to explain what’s going on, what it’s running on, and what I did or didn’t make.

It runs on a device called norns.

Norns

norns is a “sound computer” made by musical instrument manufacturer monome. It’s designed as a self-contained device for making instruments. It can process incoming audio, emit sounds, and talk to other interfaces over MIDI or other USB protocols. A retail norns has a rechargeable battery in it, making it completely portable.

There’s also a DIY ‘shield’ available, which is what you see in the above video. This is a small board that connects directly to a standard Raspberry Pi 3, and runs exactly the same system as the ‘full-fat’ norns. (A retail norns has a Raspberry Pi Compute Module in it). You download a disk image with the full OS on, and off you go. (The DIY version has no battery, and mini-jack I?O, but that’s the only real difference. Still, the cased thing is a thing of beauty.).

norns is not just hardware: it’s a full platform encompassing software as well.

norns instruments are made out of one or two software components: a script, written in Lua, and an engine, written in SuperCollider. Many scripts can all use the same engine. In general, a handful of people write engines for the platform; most users are writing scripts to interface with existing engines. Scripts are certainly designed to be accessible to all users; SuperCollider is a little more of a specialised tool.

Think of a script as a combination of UI processing (from both knobs/encoders on the device, and incoming MIDI-and-similar messages), and also instructions to give to an engine under the hood. An engine, by contrast, resembles a synthesizer, sampler, or audio effect that has no user interface – just API hooks for the script to talk to.

The scripting API is simple and expressive. It lets you do things you’d need to do musically, providing support both for screen graphics but also arithmetic, scale quantisation, and supporting a number of free-running metro objects that can equally be metronomes or animation timers. It’s a lovely set of constraints to work against.

There’s also a lower-level thing built into norns called softcut which is a “multi-voice sample playback and recording system” The best way to imagine softcut is as a pair of pieces of magnetic tape, a bit over five minutes long, and then six ‘heads’ that can record, playback, and move all over the tape freely, as well as choosing sections to loop, and all playing at different rates. As a programmer, you interface with softcut via its Lua API. softcut can make samplers, or delays, or sample players, or combinations of the above, and it can be used alongside an engine. (Scripts can only use one engine; softcut is not an engine, and so is available everywhere.)

norns even serves as its own development environment: you can connect to it over wifi and interface with maiden, which is a small IDE and package manager built into it. The API docs are even stored on the device, should you need to edit without an internet connection.

In general, that’s as low level as you go: writing Lua, perhaps writing a bit of Supercollider, and gluing the lot together.

Writing for norns is a highly iterative and exploratory process: you write some code, listen to what’s going on, and tweak.

That is norns. I did none of this; this is all the work of monome and their collaborators who pieced it together, and this is what you get out of the box.

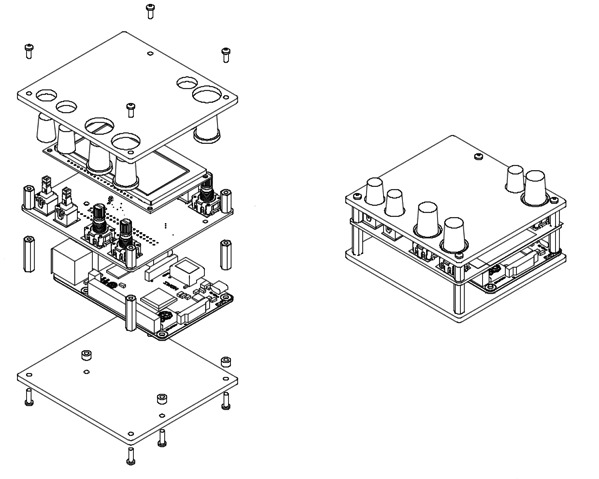

All I did was build my own DIY version from the official shield, and create some laser-cut panels for it:

…which I promptly gave away online.

Given all that: what is planetary?

Planetary

To encourage people to start scripting, Brian – who runs monome – set up a regular gathering where everybody would write a script in response to a prompt, and perhaps some initial code.

For the first circle, the brief gave three samples, a set user interface, and a description of what should be enabled:

create an interactive drone machine with three different sound worlds

- three samples are provided

- no USB controllers, no audio input, no engines

- map

- E1 volume

- E2 brightness

- E3 density

- K2 evolve

- K3 change worlds

- visual: a different representation for each world

build a drone by locating and layering loops from the provided samples. tune playback rates and filters to discover new territory.

parameters are subject to interpretation. “brightness” could mean filter cutoff, but perhaps something else. “density” could mean the balance of volumes of voices, but perhaps something else. “evolve” could mean a subtle change, but perhaps something else.

I thought it’d be fun to take a crack at this, and see what everyone else was up to.

A thing I’ve found in my brief scripting of norns prior to now is how important the screen can be. I frequently think about sound, but find myself drawn to how it should be implemented or appear, or how the controls should interact with it.

So I started thinking about the ‘world’ as more than just an image or visualisation, but perhaps a more involved part of the user interface, and then I thought about Star Guitar, and realised that was what I wanted to make. The instrument would let you assemble drones with a degree of rhythmic sample manipulation, and the UI would look like a landscape travelling past.

The other constraint: I wanted to write in an afternoon. Nothing too precious, too complex.

I ended up writing the visuals first. They are nothing fancy: simple box, line, and circle declarations, written fairly crudely.

As they came to life, I kept iterating and tweaking until I had three worlds, and the beginnings of control over them.

Then, I wired up softcut: the three audio files were split between the two buffers, and I set three playheads to read from points corresponding to each file. Pushing “evolve” would both reseed the positions of objects in the world, and change the start point of the sample. Each world would run individually and simultaneously, and worlds 2 and 3 would start with no volume and get faded in.

The worlds also run at different tick-rates, too: the fastest is daytime, with 40 ticks-per-second; space runs at 30tps, and night runs at 20tps.

I hooked up the time of day to filter cutoff, tuned the filter resonance for taste, and then mainly set to work fixing bugs and finding good “starting points” for all the sounds.. On the way, I also added a slight perspective tweak – objects in the foreground moving faster than objects at the rear – which added some nice arrhythmic influence to the potentially highly regular sounds.

In the end, planetary is about 300 lines of code, of which half is graphics. The rest is UI and softcut-wrangling – there’s no DSP of my own in there.

I was pleased, by the end, with how playable it is. It takes a little preparation to play it well, and also some trust in randomness (or is that luck?. You can largely mitigate that randomness by listening to what’s happening and thinking about what to do next.

Playing planetary you can pick out a lead, add some texture, and then pull that texture to the foreground, increasing its density to add some jitter, before evolving another world and bringing that forward. It’s enjoyable to play with, and I find that as I play it, I both listen to the sounds and look at the worlds it generates, which feels like a success.

I think it meets the brief, too. It’s not quite a traditional drone, but I have had times where I have managed to dial in a set of patterns that I have left running for a good half hour without change, and I think that will do.

planetary only took a short afternoon, too, which is a good length of time to spend on things these days. I’ve certainly played with it a good deal after I stopped coding. It’s certainly encouraged me to play with softcut a bit more in the next project I work on, and perhaps to keep trying simple, single-purpose sound toys, rather than grand apps, on the platform.

Anyhow – I hope that clarifies both what I did, and what the platform it sits on does for you. I’m looking forward to making more things with norns, and as ever, the monome-supported community continues to be a lovely place to hang out and make music.

-

Greatly enjoyed eevee's history of CSS and browser-based code; particularly, I enjoyed the moment where you're following along with things you knew… and then you viscerally go "oh, _here's_ where I began!" I twinged as I remembered where I began, my move away from table-based layout… and then the point where I started battling quirks mode for a living…

-

"Everything is Someone is a book about objects, technology, humans, and everything in-between. It is composed of seven “future fables” for children and adults, which move from the present into a future in which “being” and “thinking” are activities not only for humans. Absorbing and thought-provoking, this collection explores the point where technology and philosophy meet, seen through the eyes of kids, vacuum cleaners, factories and mountains.

From a man that wants to become a table, to the first vacuum cleaner that bought another vacuum cleaner, all the way to a mountain that became the president of a nation, each story brings the reader into a different perspective, extrapolating how some of the technologies we are developing today, will bur the line between, us, devices, and natural beings too."

Simone has a book out!

-

I was enjoying that x-height, but was going to miss the ligatures of Fira, and then I saw the ligatures, and I was in, so you know, new typeface!

-

Web-based port of Laurie Spiegel's _Music Mouse_. Instant composition; just wonderful to fiddle with. Suddenly thinking about interfaces for this.

-

Using a Raspberry Pi to emulate the memory of a NES cartridge and then outputting that data through the original NES. The making-of is good too.

-

Impressive, fun, immediate.

-

A good list of ways to protect any MCU circuit – not just an Arduino.

-

Good crunchy post on the design of the axe-recall feature in God Of War (2018); particularly interesting on how it evolved, how players perceived variance in its implementation, and the subtleties of its sound and rumble implementation. And yes, there's screenshake. It's one of the simpler functions to grok in the game, but one of its best mechanics, I think. Looking forward to more posts.

-

Beautiful. Poppy Ackroyd soundtrack, too.

-

Yeah, that. See also 'drawing is thinking' – drawing exposes the paragraphs I left out of paragraphs I wrote. I've been writing documentation recently and boy, that properly forces you to think about how to describe the thing you're doing.

-

Janelle Shane – with some effort – trains neural networks to make knitting patterns. Then knitters from Ravelry make them. I love this: weird AI being taken at face value by people for art's sake.

-

Quite like the look of Stimulus for really simple interactions without too much cruft.

-

Really rather impressive port of Prince of Persia to… the BBC Micro. From the original Apple II source code which is, of course, also a 6502 chip – although not quite the same. The palette may be rough and ready, but the sound and animation is spot on. I'd dread playing this with the original micro keyboard, though.

-

"You are a traffic engineer. Draw freeway interchanges. Optimize for efficency and avoid traffic jams." Lovely.

-

Useful, this stuff is not nearly as easy as it should be in ES.

-

Great interview with Meng Qi, with lots of lovely stuff on being both a musician and an instrument bulider. I need to return to this.

-

This feels… familiar. Two things resonated a lot, though: the description of Hymns Ancient and Modern as a tradition to come from, and especially the description of 'cramming for A-levels' – my version of that was a combination of Fopp and Parrot Records at university, and the local libraries' CD sections during my teenage years.

He's a better musician then me, though, clearly.

-

Zach Lieberman on sketching. Really good – somewhat inspiring to see somebody so fluent in visually thinking in a single platform, but also good to see what Just Chipping Away looks like.

-

Bloody marvellous: Aubrey dives deep on _precisely_ why strafejumping works, with references to the right bits of the Q3 sourcecode in github. I love this sort of videogame forensics combined with clear explanation.

-

Brilliant, long, meaty interview with Tristan Perich on his electronic music work – albums made as microcontroller code. Weidenbaum asks thoughtful, open questions, and is more than happy to just transcribe Perich's thoughtful answers.

-

An even tinier fantasy console – like a Gameboy colour, but coming with an IDE and scripting language, built around Lua. Really nice conceit.

-

A "fantasy console" – a console AND ide/language/design environment inside it for making voxelly games.

-

Lovely graphic design in the animations!