Max has finally written the brilliant article about real-time data visualisation, and especially football, that has always felt like it’s been in him. It’s in Domus, and it’s really, really good.

This leapt out at me, with a quick thought about nowness:

Playing with a totaalvoetbal sense of selforganisation and improvisation, the team’s so-called constant, rapid interchanges — with their midfielders often playing twice as many passes as the opposition’s over 90 minutes — has developed into a genre of its own: “tiki-taka”. Barça have proved notoriously difficult to beat, and analyse. Tactical intentions are disguised within the whirling patterns of play.

(emphasis mine)

It serves as a reminder of the special power to be gained from resisting analysis, of being unreadable. Resisting being quantified makes you unpredictable.

Or, rather, resisting being quantified makes you unpredictable to systems that make predictions based on facts. Not to a canny manager with as much a nose for talent as for a spreadsheet, maybe, but to a machine or prediction algorithm.

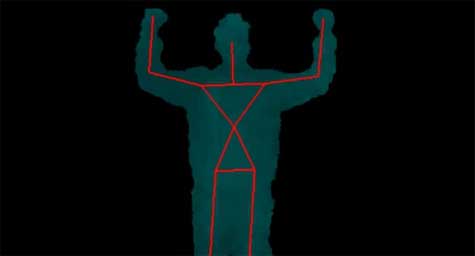

This is the camouflage of the 21st century: making ourselves invisible to computer senses.

I don’t say “making ourselves invisible to the machines”, because poetic as it is, I want to be very specific that this is about hiding from the senses machines use. And not to “robot eyes”, either, because the senses machines have aren’t necessarily sight or hearing. Indeed, computer vision is partly a function of optics, but it’s also a function of mathematics, of all manner of prediction, often of things like neural networks that are working out where things might be in a sequence of images. Most data-analysis and prediction doesn’t even rely on a thing we’d recognise as a “sense”, and yet it’s how your activities are identified in your bank account compared to those of a stranger who’s stolen your debit card. Isn’t that a sense?

The camouflage of the 21st century is to resist interpretation, to fail to make mechanical sense: through strange and complex plays and tactics, or clothes and makeup, or a particularly ugly t-shirt. And, as new forms of prediction – human, digital, and (most-likely) human-digital hybrids – emerge, we’ll no doubt continue to invent new forms of disguise.